New Gene Therapy Trials To Test Cure For Bubble Boy Syndrome

Share

New research sponsored at Children’s Hospital Boston will use gene therapy to fix the malfunctioning DNA of children with severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), popularly known as the bubble boy syndrome. SCID cripples the immune systems of children with the disorder, leaving their bodies open to fatal infections. Bone marrow transplants have shown great success in treating SCID, but they are difficult to perform and unless they have a fully matched sibling, patients can wait years for an appropriate donor. Now a new wave of gene therapy is about to begin trials, sidestepping the transplant issues altogether by reprogramming a patient’s immune system to function properly.

Last year we covered gene therapy that cures the second most common subtype of the disease, SCID-ADA. The new study, sponsored by Dr. David Williams at Children’s, just got a green light from the FDA and is currently accepting patients. The research will apply a newly developed gene therapy retrovirus to the most common form of the disease: X-SCID, which involves a mutation along the IL2RG gene on the X chromosome. The gene therapy involves taking the patient’s own bone marrow, upgrading the cell’s DNA with a functional version of the gene, and reintroducing the altered marrow.

SCID is an immunodeficiency disorder that results from a child having a defective version of one of several genes essential to producing lymphocytes (white blood cells). Without a functional immune system, the child is highly susceptible to viral and bacterial infection – without treatment, most children die within the first year of life. Sterile isolation (the infamous bubble) is necessary unless the disease can be treated in some way. Traditionally, SCID has been treated with a bone marrow transplant from a sibling or parent if one is a suitable match; if not, children often wait for years for a donation.

Approximately 1 in every 100,000 children born suffer from SCID. The disease can be caused by mutations along one of several genes, and these mutations are not always easy to screen for. Often, SCID is not diagnosed until several months after birth, once the mother’s antibodies are cleared from the body and the baby begins to develop recurring infections. Because X-SCID is due to a mutation along the X chromosome, female carriers are generally heterozygous and do not express the disease. Only males develop X-SCID.

Bone marrow transplants have been highly successful in treating SCID, especially when they are administered early in life. Ideally, a transplant would come from a full-match sibling; because not every patient has one, sometimes unmatched siblings or parents donate marrow. These transplants require drug treatments to prevent graft-versus-host disease, and are riskier to perform in infants. Transplanted cells usually do not produce antibodies, and so transplant patients require immunoglobulin injections for the rest of their lives. These complications make marrow transplants a frustrating treatment option for many families.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

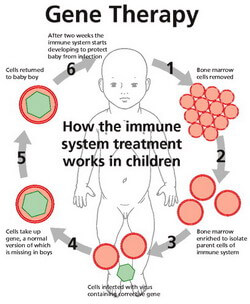

This is where gene therapy comes in. Rather than replace a patient’s faulty marrow with someone else’s, gene therapy reprograms the patient’s own genome by inserting new DNA to fix broken genes. First, bone marrow samples are taken from the patient. Next, a vector (e.g. a virus or retrovirus) is used to insert DNA into the marrow cells; this genetic material binds with the patient’s own, upgrading their genome to include the missing gene. Finally, the marrow is reinserted into the patient, where it can generate the lymphocytes that SCID patients lack. There is no risk of graft rejection with a patient’s own cells, and there is no need to wait for an acceptable donor. Antibodies can even be produced by the upgraded cells, eliminating the need for immunoglobulin injections.

One risk of gene therapy is that the DNA is often inserted randomly into the patient’s own genome. If the added DNA is inserted into the middle of an important gene – say, a gene that normally controls cell division – it can disrupt that gene’s function and result in cancer. Gene therapy for X-SCID has been controversial since 2005, when five children in Europe got leukemia from the retrovirus used in experimental treatments.

Since then, the Transatlantic Gene Therapy Consortium – an international collaboration between multiple institutions – set about completely redesigning the vector used to upgrade the patient’s genome. The retrovirus used in the current study is the first X-SCID treatment to be approved by the FDA since 2005, and underwent extensive regulatory review prior to approval. Researchers are looking for twenty subjects to undergo a one-time treatment; the children will be monitored for leukemia for fifteen years following the initial gene therapy.

Though it is a rare disease, SCID entered the cultural consciousness in the 1970’s and 80’s through extensive media coverage of David Vetter, dubbed “the boy in the plastic bubble.” Vetter died in 1984 following an unmatched bone marrow transplant from his sister, a transplant which inadvertently infected David with the Epstein-Barr virus.

The Consortium is an international collaboration that includes researchers from Children’s Hospital Boston, Hannover Medical School (Germany), and Institute of Child Health (London). Information on subject recruitment can be found here.

[images courtesy of KBIO2.com, stemcellcordblood.net]

Drew Halley is a graduate student researcher in Anthropology and is part of the Social Science Matrix at UC Berkeley. He is a PhD candidate in biological anthropology at UC Berkeley studying the evolution of primate brain development. His undergraduate research looked at the genetics of neurotransmission, human sexuality, and flotation tank sensory deprivation at Penn State University. He also enjoys brewing beer, photography, public science education, and dungeness crab. Drew was recommended for the Science Envoy program by UC Berkeley anthropologist/neuroscientist Terrence Deacon.

Related Articles

Sparks of Genius to Flashes of Idiocy: How to Solve AI’s ‘Jagged Intelligence’ Problem

US Solar Surged 35% in 2025, Overtaking Hydro for the First Time

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

What we’re reading