Amino Acids Extend Mice Life 12% – Could It Work On Humans?

Share

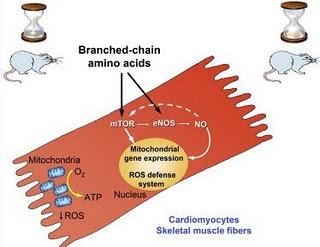

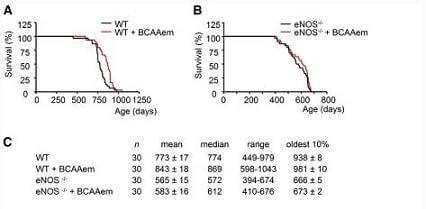

Researchers in Italy may have struck upon a health supplement that could extend life. Enzo Nisoli and colleagues developed a cocktail of amino acids and gave it to mice via their water supply. Those mice that received the supplement had a longer median lifespan - 869 days compared to 774 days in the control group, an impressive 12% increase. As recently reported in the journal Cell Metabolism, the mice were all middle aged when testing began, and those given amino acids showed increased energy, muscle coordination, and stamina. Essentially the cocktail helped the middle aged mice stay more youthful. Nisoli believes that the antiaging effects of the amino acids were due to increased production of mitochondria, and lower incidence of damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS), associated with free radicals. The amino acids used in the cocktail (leusine, isoleusine, and valine) are known as branched-chain amino acids (BCAA) and are already found in many widely used health supplements! With further research it may be possible to understand if increasing BCAA levels in humans could extend our healthy youthful years as well as it does in mice.

Extending the life of mice is one of the most common metrics for evaluating longevity treatments. The Methuselah Foundation uses mice as the basis for deciding the winners of its MPrize, an award to encourage research in lifespans. As we discussed previously, the leaders in the MPrize have impressive records - Stephen Spindler got median lifespan of mice to reach 1356 days! That's considerably better than recent Italian work, but I'm still more impressed with Nisoli. Why? Spindler, and many others, use calorie restriction to promote longevity. I don't think humans can really use that technique. Eating very little while not being malnourished is hard, and frankly not very enjoyable. Nisoli and his colleagues used a cocktail of commonly available amino acids that almost anyone could take as a health supplement. BCAAs are really cheap too.

But before you go off to the vitamin store and stock up on amino acids, we should discuss the limitations of this experiment. First and foremost, the work is in mice. Yes, mice are one of the most common test animals for longevity, and yes, the same BCAA cocktail also worked with yeast cells (another common test organism), but none of that means that humans are guaranteed to benefit. Second, the mice used were all males, and as we've seen with previous work in longevity, some techniques simply do not translate from one sex to another. Third, only 30 mice were used in the BCAA test group (30 in the control as well). That's simply not a very big sample (though Spindler only used 6 to set his record). According to The Telegraph, Nisoli is calling for larger scale experiments, but few institutitions seem willing to sponsor research into health supplements and there's not much profit to be made since BCAAs are so widely available and relatively cheap. Finally, we should point out that while the Italian experiment showed a 12% increase in median lifespan, the range of lifespans didn't improve nearly as much. Maximum longevity for the BCAA mice was 1043 days compared to 979 days in the control group - a more modest 6.5% increase. If we look at the top 10% of mice in each group, the BCAA mice only improved 4.5% (981 compared to 938). In other words, while the amino acid treatments helped the mice live longer as a group, they didn't produce any super old mice. To apply it to humans: it would be like more people reaching 80, or even 90, but still no one would live to 125.

Some of the most useful information out of this experiment dealt with understanding how BCAAs could improve the health and youthful vigor of those in middle age. The amino acids increased the production of mitochondria, the energy suppliers of the cells, but only in cardiac and skeletal muscle tissues. Fat tissue and the liver were unaffected. That's probably a really good thing as we don't want to unbalance those systems. BCAAs seem to increase SIRT1 activity - the protein linked to the benefits of resveratrol; which in turn is the substance in red wine associated with longevity. BCAAs, probably through mitochondrial regulation, seem to negate ROS which cause oxide damage - another important factor in helping people live longer and healthier lives.

The experiment spent considerable energy exploring the role of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), an enzyme that regulates nitric oxide (NO) in the blood. In previous work, Nisoli has found that decreased NO leads to increases in mitochondria. In genetically altered mice who had their NO regulation disrupted, the benefits of BCAA were much smaller. This suggests that, as Nisoli theorized, the mitochondria really are the cornerstone of increased longevity and energy, and that BCAA works through mitochondria regulation.

That information may have far reaching effects in other longevity studies. In fact, it's kind of amazing how the results of different experiments are already finding complementary answers. SIRT1 (and other sirtuins) seem to be a key element and are affected by BCAA production. Scientists discovered a gene related to production of mTOR protein and rapamycin that could be removed to make them live 20% longer - and mTOR is also part of the mechanism used by BCAAs interacting with mitochondria. Russia's recent 'cure for aging' relies on antioxidants, and BCAAs seem to fight ROS damage. While each study in lifespans only produces moderate success, together they are revealing a more complete understanding of how our cell chemistry could be altered to fight aging.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

I try not to get too excited about longevity discoveries that are still being tested on animals as it's simply too soon to know how they'll pan out with humans. Yet I'm very hopeful about the work from Nisoli and his colleagues. It would be relatively easy for us to increase our BCAA intake. Many people already use these amino acids as supplements after weight lifting workouts. Not only that, but the benefits shown in mice - increased energy, better coordination, more youthful stamina - are what we'd all like to enjoy when we reach middle age. Of all the prospective ways to moderately increase lifespan, BCAAs seem to be the easiest to employ - no genetic modifications, no drinking tons of red wine. I really hope that Nisoli or other researchers will receive the funding they need to further explore the benefits of amino acids. If the tests had larger sample sets, and were repeated across several labs, I'd start taking BCAAs today.

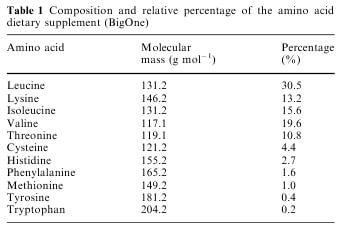

*UPDATE 10/15/10: At the request of readers (via email and the first comment below) I have been asked to share the proportions of the BCAA supplement given to the mice in the experiment listed above. Before I share this information, I would like to make it very clear that I am in no way promoting the use of these supplements, nor do I verify that they are safe to take, nor do I, in anyway, suggest that they will positively affect your lifespan. I am not a doctor, nor a biologist. I am excited about the potential of this work, but that's not an endorsement to take any particular supplement.

But science demands we share information, so here we go.

Nisoli bases his BCAA enriched mixture (BCAA-em) on earlier work on mouse muscle in 2005. Guiseppe D'Antona was a researcher for that experiment as well as the lead author for Nisoli's recent work. The amino acids seem to have been taken from a commercial supplement from Professional Dietetics in Milan called BigOne

For both experiments, mice were given 1.5mg/g of body weight in their water each day. The ratio for amino acids can be seen in the table below (taken directly from Pellegrino et al European Journal of Applied Physiology 2005). The Nisoli paper discussed in the article above doesn't specify whether they used the BigOne supplement or reproduced its contents.

[image credits: Rama via WikiCommons, D'antona et al Cell Metabolism 2010]

[sources: D'Antona et al Cell Metabolism 2010, Telegraph.co.uk]

Related Articles

These Genetically Engineered Brain Cells Devour Toxic Alzheimer’s Plaques

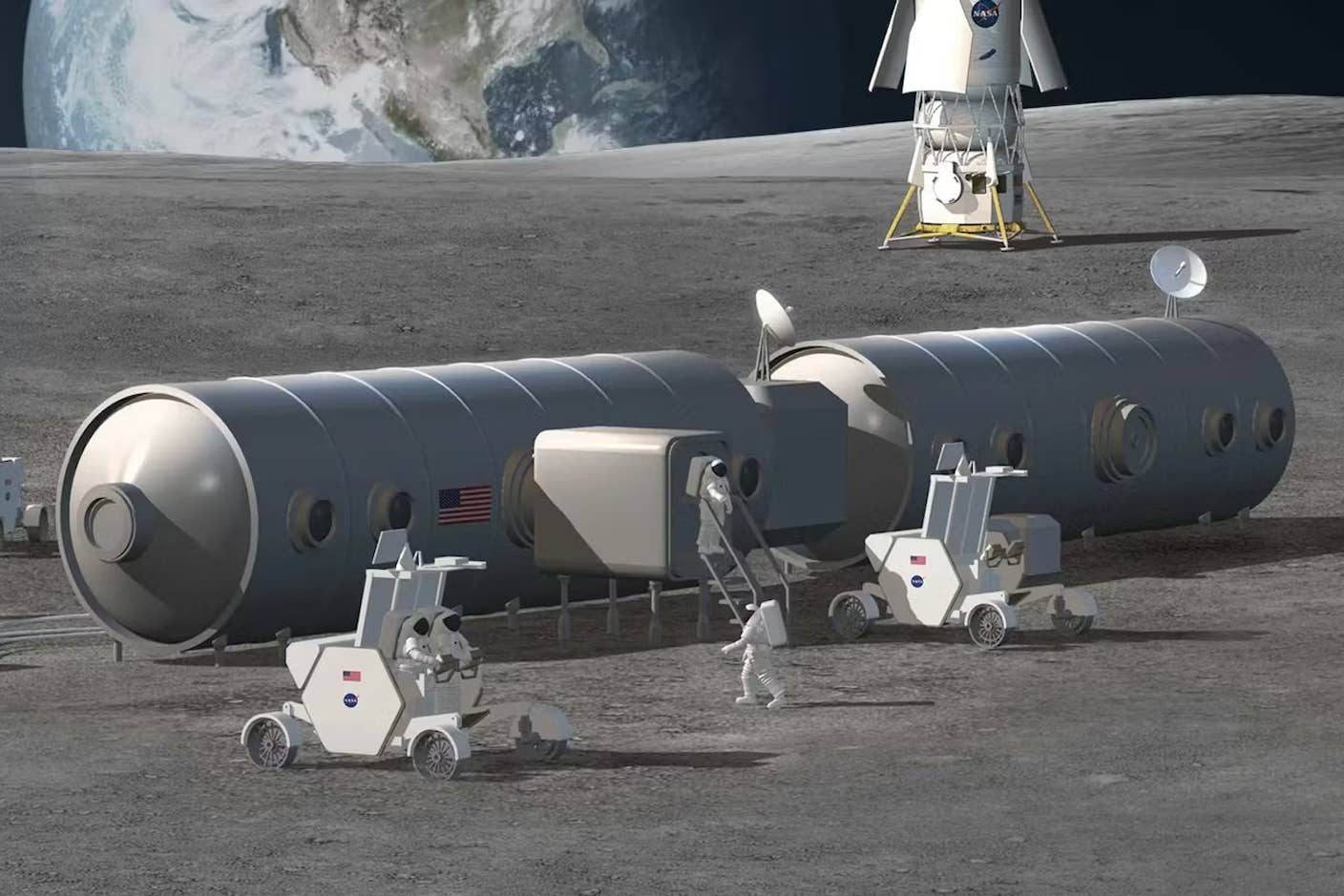

The US Plans to Break Ground on a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

What we’re reading