Test Tube Babies Reach Major Milestone: 5 Million Born Since 1978

Share

It's time to applaud fertility specialists for all their baby making efforts: an estimated 5 million "test tube babies" have been born worldwide since the first successful in-vitro fertilization (IVF) birth in 1978. Delegates of the non-profit organization International Committee Monitoring Assisted Reproductive Technologies recently made the announcement based on data from 2008 and estimates of 350,000 IVF births annually for each of the last 3 years. The figures were reported at the 28th annual meeting of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology.

Assisted reproductive technology that has enabled millions of couples who suffer with infertility to have children biologically, but not without controversy.

The World Health Organization estimates that infertility affects between 10 to 15 percent of reproductive-aged couples, which translates to around 80-100 million couples globally. For these couples, IVF is often the only viable possibility for having their own children. In the U.S. alone, around 1 percent of all infants born annually are conceived via IVF, which is about 61,000 infants out of nearly 155,000 procedures performed. Since first introduced in the States, around half a million IVF babies have been born.

The procedure for IVF involves removing a female's eggs from the ovaries, fertilizing them in the laboratory with male-donated sperm, and delivering embryos into the uterus for implantation. Egg retrieval is part of the broader IVF cycle, which includes treatment with hormones to promote egg maturation. But age affects fertility, especially as women approach 40. In women under the age of 35, success rates of pregnancy from IVF embryos are 33 percent per cycle, but those rates drop steadily with increasing age, down to 12.5 percent in women aged 40-42. The overwhelming reason that most cycles are discontinued is no or inadequate egg production and the rate of miscarriage rises rapidly after age 40.

Though the technique had been shown to be safe, the use of IVF got off to a slow start. The first successful IVF baby, Louise Brown, was born in 1978 in Britain to John and Lesley Brown, who had been trying to conceive for 9 years (you can even watch the original news footage of Louise's birth here). By 1984, only 350 test tube babies had been born and it wasn't until 2001 when the number neared one million. Today, about 1.5 million cycles are performed each year, and the numbers continues to climb. In 2010, the Nobel committee awarded Robert G. Edwards, the pioneer of IVF, with the Nobel Prize in Medicine.

But even as this milestone is a great accomplishment in medicine, technology, and public health, the problems surrounding IVF since it was introduced linger.

One of the longstanding issues of the technique is its expense, especially in developing countries where the technology is out of reach to many. According to the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, the average cost of one IVF cycle was $12,400 in 2006, but many couples attempt more than one cycle, especially women over 35. Even in the present U.S. economic climate where fewer people have access to quality healthcare, IVF is thought of as more of luxury than a medical necessity. Efforts to decrease the cost of IVF in developing countries have been suggested and the Internet is ripe with stories about "cheap IVF", but whether the $12k-price tag has actually dropped, without compromising success rates significantly, has yet to be reported.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

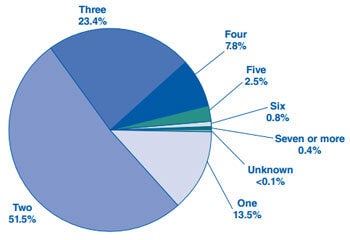

The likelihood of multiple births with assisted reproductive technology has also been severe: between 1980 and 1998, the rate of high order pregnancies (triplet or more) in the U.S. increased by 423 percent. Many in the public became aware of and outraged by this issue through tabloid-esque coverage of Nadya Suleman or the Octamom as she is known, who gave birth to octuplets in 2009 after IVF treatments and is now on public assistance.

Fortunately, the practice of transferring multiple embryos at once is diminishing thanks to ongoing research showing transfer of a single IVF embryo is just as if not more effective than multiple or even two embryos at once. According to Dr. Anna Pia Ferraretti, chairman of the society's IVF Monitoring Consortium, European practices have reduced the transfer of multiple embryos, such that IVF deliveries in 2009 included less than 1 percent of triplets and 20 percent of twins.

For all the controversy surrounding the technology, such as religious groups who voice opposition to the discarding of unneeded embryos, use of IVF is sparse. Consider that currently 133 million babies are born worldwide every year, so IVF births make up only one quarter of one percent of all live births annually, barely a blip on the reproductive radar.

The promise of IVF is translating into a seemingly exponential rise in its use, but more advances are needed in assisted reproductive technologies. Improved success rates, screening methods that enhance specificity, inexpensive solutions, technologies with low barriers to entry, and embryonic genetic testing are hopefully in the not-too-distant future. These strides would not only be beneficial to couples turning to medical assistance to have children, but they would go a long way in resolving criticisms, both ethical and pragmatic, that continue to cast IVF in a negative light.

In the end, this milestone means that 5 million human beings can say that medical science is absolutely responsible for their existence. Chalk up another win for technology.

[Sources: American Society of Reproductive Medicine, ICMART, LiveScience]

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

What we’re reading