Finland’s Next Laws To Emerge From Online Crowdsourced Proposals

Share

Why isn't that a law?

You may have muttered this phrase or heard someone else say it out of frustration, but chances are that question has popped up in conversation in one form or another. It's the universal plight of citizens to feel underrepresented by their government, expressing their frustration at what is and isn't legal. But the political winds of change are gaining momentum, and governments are beginning to see the value of the crowd, as opposed to the masses, in shaping legislation.

Case in point: Finland now allows citizens to propose new laws online, and if an initiative gathers enough votes, the government must vote on it.

This year, Finland has taken two huge steps to make crowdsourced laws a reality. First, its constitution last March was modified to allow every citizen proposal that collects a mere 50,000 signatures to get voted on by Parliament. In response, a non-profit group of Helsinki entrepreneurs started a website called Open Ministry to allow people of voting age to propose initiatives online. The website uses APIs from banks and mobile operators to confirm identities. Recently, the Finnish Parliament approved the platform after verifying that the electronic identification process is secure.

The cofounder of Open Ministry Joonas Pekkanen explained that "The citizens initiative can be either of two formats. They can either be very general proposals for requesting the government to take action upon some issue. Or they can be --and this is what Open Ministry is focusing on -- they can be in the format of actual law proposals with the actual clauses, legal language, and same format as the bills would be that come from the government."

The legislation creating Parliament in Finland (seen here from above) is now more accessible to citizens than ever.

While proposing ideas is easier, Parliament will have to alter the language of the bill appropriately, whereas a bill in the correct legal language will be harder for members of Parliament to change, and a simple yes/no vote may be taken. If officials vote in favor of a proposal written as the court requires, it would become law immediately.

What's great about this new system is that only 50,000 people need to back an initiative for government officials to consider it. Finland has 4.2 million people who are of voting age, which translates to around 1.2 percent of voters. Compare this to California, for instance. The Golden State allows initiatives to be put on a ballot if around 800,000 signatures are collected or 4.7 percent of the state's 17 million registered voters. Not only does Finland require only a quarter of what California does to get a ballot considered, but 50,000 is a much more reasonable number for a grassroots movement, in the ballpark of one-sixteenth the amount.

More than that, Finnish voters can back an initiative online rather than being physically approached by solicitors. Not only does that make it more convenient, but voters can study the initiatives in more detail and research information before they sign up, something that is much harder to do when someone is pushing a clipboard in your face to sign.

Now in places where Internet access is not as widespread, the online process would seem partial. But this is Finland, where Internet use is near 90 percent thanks to a law in 2009 that made fast online access a legal right. For comparison, California has 84 percent online use among the population. Globally, the rise of smart phones will make online access nearly universal in a short period of time, such that online platforms like Open Ministry could be supported in a variety of countries, as long as they could be secure from being hacked.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

So after launching recently, how successful has the crowdsourced system worked?

To date, it has contributed a handful of votes to proposals that were started back in the spring with the revised Constitution. One of these is a proposal to ban farming of animals for fur, which is on the cusp of hitting the 50,000 signature threshold. Still, the ease of online access may be more than a complement to physical signature collection. Speaking to Deutsche Welle, Pekkanen said that "a realistic target is that we would have one [initiative originating on the website] before parliament within a year."

Crowdsourcing laws may just be the next big thing. Not only is the crowd finding greater economic strength and market influence through crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter, but governments have already implemented a number of means by which the populace can engage their governments. For example, the White House website allows users to post petitions about issues and with enough signatures, the administration says it will consider the issue and respond to it. Also, Americans Elect was an effort to allow online users to pick a presidential candidate, but earlier this year it failed in its efforts to do so. But the biggest crowdsourcing effort probably belongs to Iceland, which has recently seen citizens approval of a new constitution that was estimated to be crafted by over half of eligible voters, in one way or the other.

The success of Finland's efforts will no doubt be watched by other governments and their citizens, though many countries will likely not follow suit anytime soon. Just

For those interested in learning more about Open Ministry, check out the following interview with Pekkanen on Utopia News:

images: chriszak on Flickr, finland.fi

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

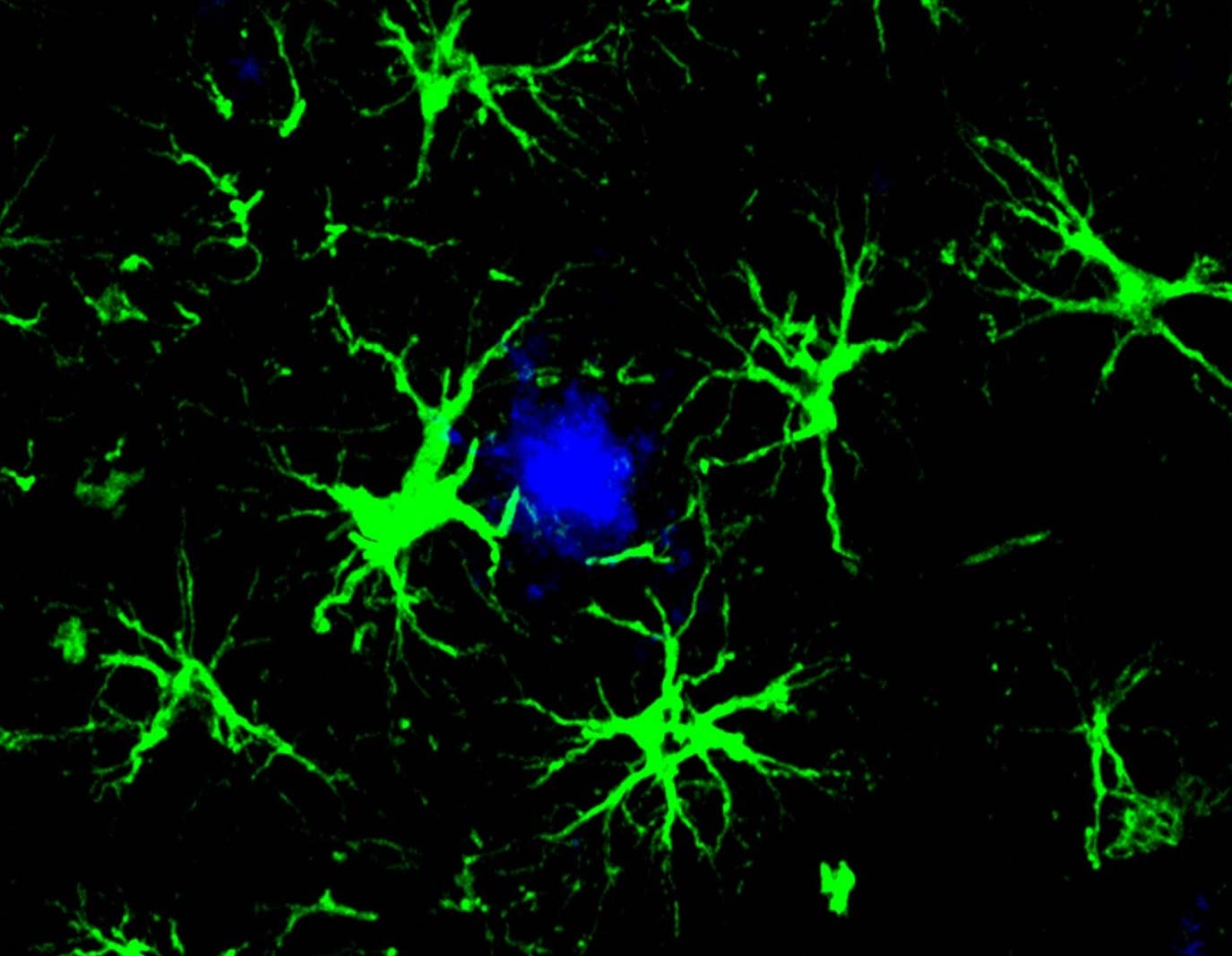

These Genetically Engineered Brain Cells Devour Toxic Alzheimer’s Plaques

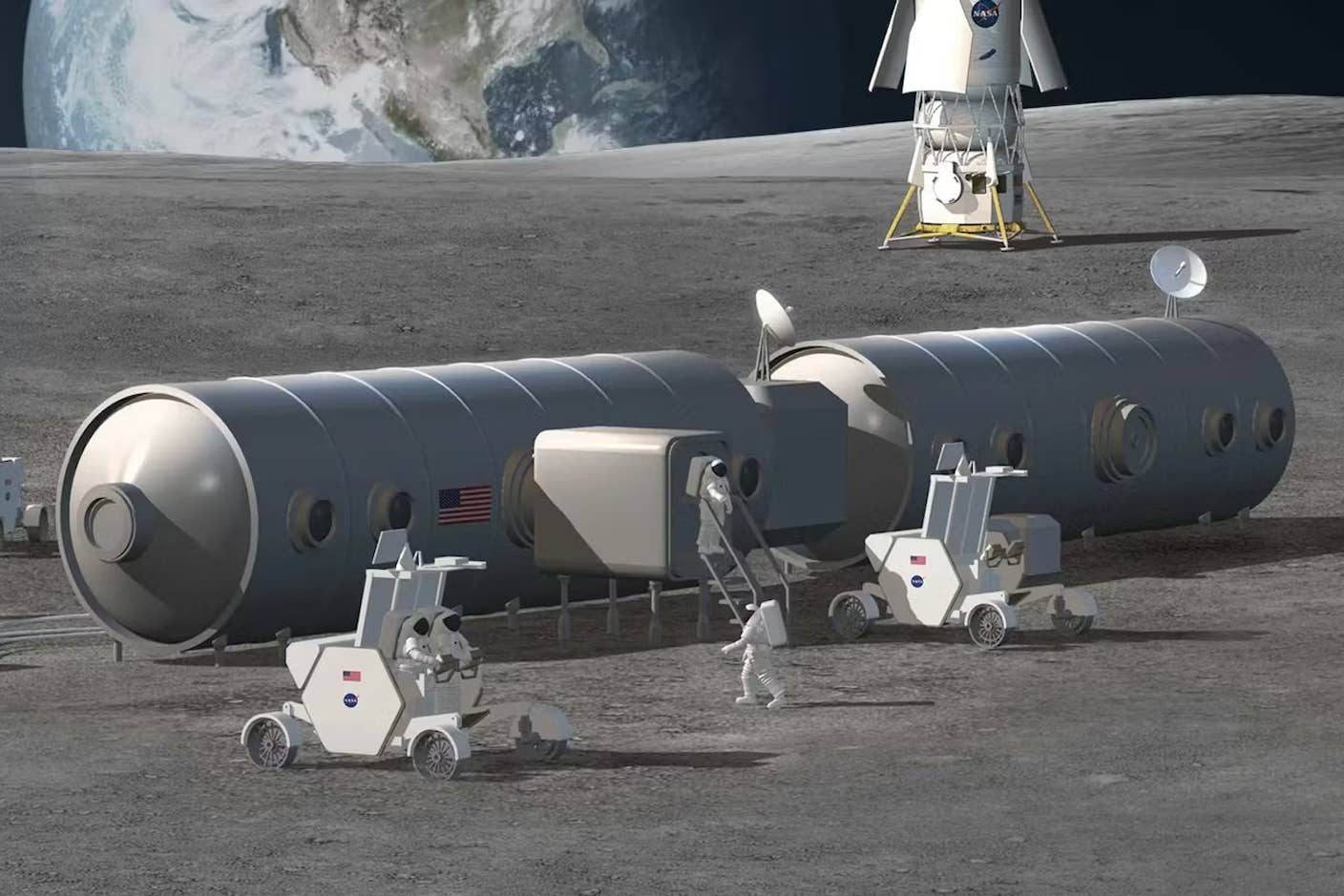

The US Plans to Break Ground on a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

What we’re reading