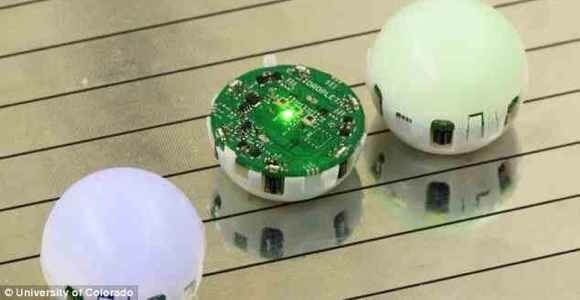

Robots that look more like ping pong balls could one day help to colonize Mars, so thinks their developer. The robots would work together in swarms of thousands to construct habitats for humans and perform gardening tasks.

The ping pong bots, or, “droplets” as they are known by their creator Nikolaus Correll, an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, are still in the prime of their development. The 20 that have been built so far have RGB color and infrared sensing, get around with vibrating motors and communicate via wireless. Down the road Correll hopes to have a completely autonomous swarm robot platform through distributed sensing, actuation, computation and communication that can be used for just about any kind of remote sensing or even construction tasks.

He views the swarm as a “liquid that thinks” with virtually no limit to what the robots could potentially accomplish, and likens them to the “swarm” of cells that make up our bodies that can serve a bewildering array of diverse functions. The robots could be deployed to contain an oil spill, says Correll, or assemble into useful bits of hardware after being launched individually into space. They could even assemble to construct a habitat on an alien planet, if humans were to explore Mars, for example.

But the droplets are still in the early developmental stages and are far away from becoming the intelligent, multi-faceted swarm that Correll foresees. The software that allows their sensors and processors to communicate is still being written and the only swarming the robots have done so far has been through computer simulations (in which hundreds were shown to coordinate). For now Correll plans to use the droplets to demonstrate self-assembly and emergent swarm behavior to carry out pattern recognition, sensor-based motion and adaptive shape change. These behaviors could eventually be scaled up to perform the same tasks in the 3D space of air or underwater.

The versatile platform will be modified with different sensors depending on the task required. Correll has published the software code that facilitates communication between droplets online so other developers can build on what’s already been established. He also hopes to come up with a methodology that would allow for complex aggregations such as assembling parts of a space telescope, for example, or airplanes and jets.

The droplets should be incorporated as part of the natural evolution of a project Correll and colleagues began in 2008 to create a robotic greenhouse. The project originally involved iRobot’s Roomba-like but more programmable Create robots. The continuing goal of the project is to use a robot network to create a precision agriculture system of maximum efficiency. Sensors on the robots monitor the “local environment conditions” of the plants so that water and nutrients are delivered locally and on-demand and fruit is harvested in an optimal fashion. Combine the greenhouse with its self-assembling capabilities and the droplets could one day, Correll envisions, be used to establish “habitats and lush gardens for future space explorers.”

A swarm of tiny, simple robots probably won’t ever be as sexy as the humanoid robots like Asimo and Nao or the tireless assembly line bots like those being installed at Foxconn, but the strength of swarm robotics lie in their numbers. With hundreds, thousands, even tens of thousands of robots the amount and type of complex behaviors that could possibly emerge from a simple set of rules is virtually limitless. Their sheer numbers also means they’re disposable. If a swarm includes a thousand robots, losing even a hundred of them (because they were cheaply made) won’t appreciably affect overall performance. Swarm robotics is a field in its infancy, but thanks to ambitious developers like Correll trying to push the boundary, this exciting field of robotics is moving forward.