Solar Continued Exponential Growth in 2012, But Politics May Stymie Growth

At any given moment, the sun bathes the earth in enough solar energy to power the world 10,000 times over. Capturing and converting that energy into usable electricity presents major technical challenges. And, for the time being, an international tangle of politics and prices complicates matters further.

Share

At any given moment, the sun bathes the earth in enough solar energy to meet its power needs 10,000 times over. The challenge lies in capturing and converting that energy into usable electricity. And, for the time being, an international tangle of politics and prices also complicates matters.

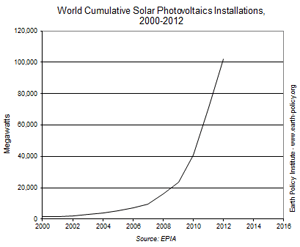

Solar power represents a tiny fraction of the total power used globally, but its use has been growing exponentially in recent years. That trend continued in 2012, according to recently released analyses from the Interstate Renewable Energy Council and Earth Policy Institute.

In the United States, solar energy installations increased by 80 percent in 2012, gaining roughly 3.3 gigawatts of capacity. Utilities have added much of the new capacity, showing mainstream buy-in to the cleaner energy source.

Globally, solar power grew by roughly half in 2012, as 31 gigawatts of solar photovoltaic power were installed. More capacity was added than in any previous year, and total gigawatts exceeded 100 for the first time.

Falling prices on solar equipment, which represent most of the cost of solar projects, have driven adoption. The average cost of a completed PV system dropped by more than 25 percent in 2012; since the beginning of 2011, prices have fallen by more than half.

Falling prices and exponential growth curves suggest that solar power may eventually compete with traditional fossil fuel energy sources. But in the short term, governments could push prices back up as they roll back subsidies and tack on tariffs.

Germany, the country with more solar power than any other, has built its solar arsenal thanks, largely, to tax incentives. (It’s a small arsenal: Even the world solar leader gets just 5 percent of its power from the sun, according to Earth Policy Institute.) Italy has similar incentives. Yet both countries are rolling the subsidies back, which could slow the rate of solar adoption in Europe.

The “made in China” issue has been the biggest political struggle over solar power in recent years. China — which now makes 60 percent of all photovoltaic, or PV, equipment — has extended generous state help to its manufacturers, leading them to offer a glut of low-priced equipment on the international market.

Both Europe and the United States have accused China of “dumping,” as their manufacturers have struggled to compete.

“The PV space is getting better, but the reason has a little to do with technology but a lot more to do with the giant factories in China. They’re building at an unprecedented scale,” Gregg Marinyak, Singularity University’s chairman of energy and environmental systems, told Singularity Hub.

According to the Solar Energy Industries Association, “The sharp fall in prices, due in part to a global oversupply, has put a serious strain on solar manufacturers worldwide.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

PV equipment production did indeed shrink, by 2 percent, for the first time ever in 2012. Still, the dip in manufacturing won’t last in the face of continued demand for solar, according to EPI.

But U.S. manufacturers have been vocal about what they see as unfair competition from China. Lower prices are good for consumers, but if they dip down too close to production costs, they make homegrown manufacturers unhappy.

In May, the U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panels, bumping up the price U.S. consumers pay. (Europe also required China to charge higher prices for solar panels it sells there.) In response, the Chinese subsequently imposed tariffs on imports of U.S. polysilicon, an ingredient in the dominant commercial type of photovoltaic modules, crystalline silicon.

The tariffs could, at least in the short term, slow the U.S.’s move to cleaner energy, according to Gary Hufbauer of the Peterson Institute of International Economics.

“It will make solar panels more expensive to anybody who wants to install them here. I mean, as a policy to slow down renewable energy, this is great,” Hufbauer said in a podcast.

But solar power is a rapidly changing industry, and industry players continue striving to make their products cheaper and better in order to drive widespread adoption.

“These are short term effects,” Marinyak said of the price wars. “And there are some technical things that could really, really help the adoption of large-scale solar.”

For example, solar thermal energy setups, which use the heat rather than the light of the sun to produce energy, are gaining traction in the United States and Spain. And any improvements to how utilities can store energy for later use would dramatically sweeten the pot for the major players to use more solar power.

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

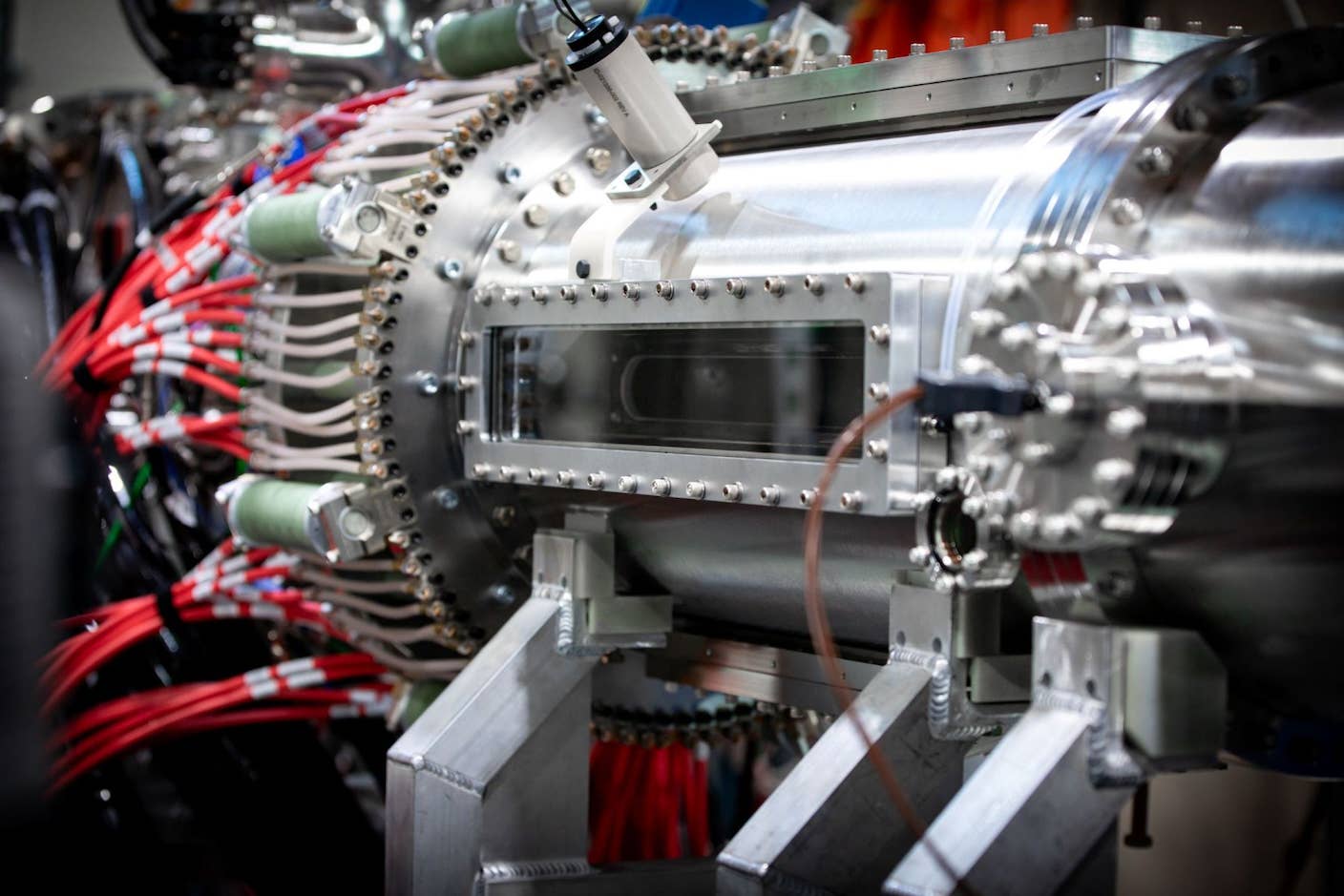

Startup Zap Energy Just Set a Fusion Power Record With Its Latest Reactor

Scientists Say New Air Filter Transforms Any Building Into a Carbon-Capture Machine

Investors Have Poured Nearly $10 Billion Into Fusion Power. Will Their Bet Pay Off?

What we’re reading