Algorithm Tracks Literary Emotion in Shakespeare, the Brothers Grimm

Computers are excellent at crunching numbers, looking for words, following a logical set of instructions. But our machines are still highly literal beasts. The subtleties of human emotion largely escape them. Which is why Saif Mohammad—a Research Officer at the Institute for Information Technology, National Research Council Canada (NRC)—wants to inject emotional color into algorithms for research, search, and maybe more.

Share

Computers are excellent at crunching numbers, looking for words, following a logical set of instructions. But our machines are still highly literal beasts. The subtleties of human emotion largely escape them. That's why Saif Mohammad—a Research Officer at Canada's Institute for Information Technology—wants to inject emotional color into algorithms for research, search, and maybe more.

In a recent paper, Mohammad and his team showed how an algorithm with emotional IQ might help researchers in the social sciences more efficiently mine data from large literary collections.

To build their “emotional analyzer,” the team needed to associate thousands of words with their emotional meaning—joy, trust, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation. To accomplish this huge and often subjective task, Mohammad and his team turned to the crowd to build a word-emotion “lexicon.”

Tens of thousands of online participants provided over a million responses on which words were associated with which emotions. The team culled the answers by asking a multiple choice question on each word’s literal definition. If a participant got the answer wrong, the response was discarded. If a person got 75% or more of the questions wrong, all their responses were discarded.

Lexicon in hand, the team trained the emotional analyzer on a large selection of novels and fairy tales to measure the word density of various primary emotions. “Our research is aimed at making computers understand emotions in text,” Mohammad told Singularity Hub, “Stories, especially fairy tales, are a powerful source of emotions.”

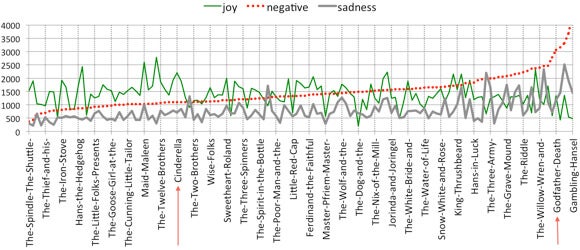

After scanning Grimms' Fairy Tales, for example, the team generated an emotional spectrum, from light to dark. "Cinderella" falls on the lighter side of life, using more joy words relative to words associated with sadness. Meanwhile, "Godfather Death," one of the darkest of the fairy tales, is just the opposite.

An emotional spectrum of Grimms' Fairy Tales, from light to dark. (Due to space constraints not all fairy tales are listed.)

Or take Shakespeare’s tragedy, Hamlet, compared to his comedy, As You Like It. As you might expect, the analyzer shows the tragedy has relatively fewer words associated with joy and trust and more associated with fear, sadness, disgust, and anger.

More broadly, the paper compared fairy tales to novels and found, on average, fairy tales have a higher density of emotive words, even as they vary more around that mean. Further, fairy tales use more words with a positive emotional association than a negative association.

Such inquiries may seem useful only for a specific niche, but Mohammad thinks his system can objectively study big social questions too.

“With computers we can analyze literature at a much larger scale than what was possible before,” Mohammad says, “For example, we can now track the change in emotions associated with an entity (say a country, or a group of people) through time by looking at mentions in millions of books published over the last few centuries.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The paper examined emotions in proximity to the words America, India, Germany, and China since 1800. Spikes in words associated with fear appeared correlated to historical events, like the Boxer Rebellion, World I, and World War II.

But of course, the applications aren't limited to literature. According to Mohammad, his team is “already working on tweets, Facebook posts, emails, newspaper articles, blogs, and other forms of text.”

Ultimately, he thinks emotion-based software may help us better keep tabs on depression or online harassment and bullying, track emotions on Twitter to forecast riots and better deploy resources, or measure sentiment towards government policies and controversial issues.

Such software may also improve our interaction with characters in video games, virtual nurses or tutors, physical therapy robots, or customer service call center systems.

“In all of the above scenarios, it is useful for the computer agent to recognize whether the person is in a neutral, happy, angry, sad, or frustrated state,” Mohammad says, “Often the different states are best handled by different responses.”

Though they’ve come a long way, there’s yet work to be done. The subtleties of language extend beyond simple word-emotion associations. Context matters too.

“We now have a good idea of what emotions words convey, but words can combine in sentences in unique ways to convey meaning and emotions. Detecting emotions and meaning from whole sentences is one of the biggest challenges for computers.”

Chart Credit: Saif Mohammad, From Once Upon a Time to Happily Ever After: Tracking Emotions in Novels and Fairy Tales.

Image Credit: Randy Robertson/Flickr; John Lambert Pearson/Flickr; Paul/Flickr

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Sparks of Genius to Flashes of Idiocy: How to Solve AI’s ‘Jagged Intelligence’ Problem

What we’re reading