MIT’s Tangible Media Group Gives Digital Bits Physical Form

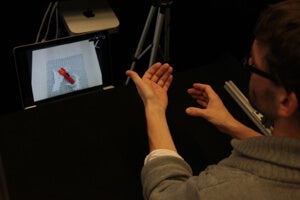

MIT’s Daniel Leithinger sits in front of a screen displaying video of a red ball on a table. Leithinger raises up his hands and a field of columns erupts from the table, forming a pixellated physical model of his hands in real time. Leithinger’s hands have been digitally transported from one room to another and physically re-manifested using a “tangible user interface.” He can pass the ball from one hand to the other or manipulate objects without being physically present.

Share

MIT’s Daniel Leithinger sits in front of a screen displaying video of a red ball on a table. Leithinger raises up his hands and a field of columns erupts from the table, forming a pixellated physical model of his hands in real time.

Leithinger’s hands have been digitally transported from one room to another and physically re-manifested using a “tangible user interface.” He can pass the ball from one hand to the other or manipulate objects without being physically present.

Leithinger built the system, called inFORM, with fellow Ph.D. candidate and graduate research assistant, Sean Follmer, and Professor Hiroshi Ishii, head of MIT’s Tangible Media Group. The team hopes their invention and others like it will augment graphical user interfaces, like screens, by giving physical 3D form to bits of data.

People may one day use such smart, interactive surfaces to view and edit 3D models, tilt mobile devices to view incoming calls or messages and more comfortably use touch screens, manifest a remote user’s hands to interact with objects—or for any number of other as yet unforeseen applications.

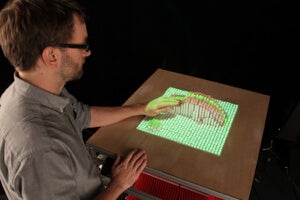

The inFORM interface is composed of 900 polystyrene pins. Attached to an array of actuators and a computer, the pins extend up to four inches above the surface of the table in a rough approximation of whatever 3D model the computer commands. Using Microsoft Kinect, inFORM tracks users and objects and overlays visual information with an overhead projector.

In action, it’s a compelling sight, and Ishii’s group thinks such interfaces might lend a more elegant, intuitive design to human-computer interaction.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

But inFORM isn’t ready for the rest of us just yet. The system’s resolution is quite low. And the group notes in a paper detailing the project that the currently required one actuator per pin limits how much the resolution can be scaled—adding more pins would rapidly increase the system’s footprint and cost.

That said, the principles are sound, and combining what they’ve learned with different interaction methods or novel materials may yield more user friendly or higher resolution surfaces. The group, for example, has experimented with pneumatically controlled materials and malleable materials like “tunable clay.”

Other improvements might include touch sensors in each of the table’s 900 pins to complement Kinect tracking.

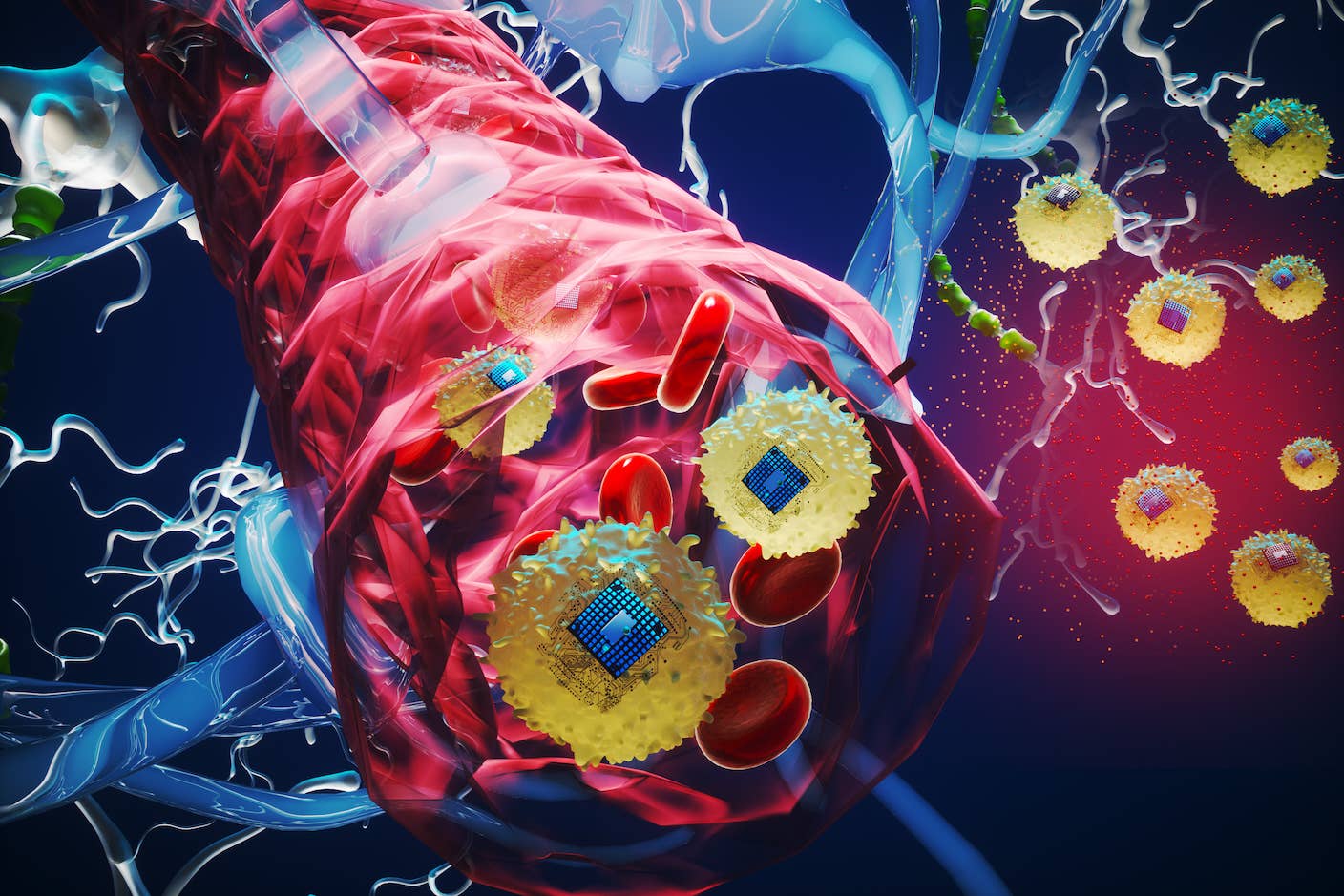

The Tangible Media Group compares tangible media interfaces to an iceberg where only a portion of the digital information emerges in the real world. The ultimate goal is something they term Radical Atoms—or materials (nanomachines, perhaps?) that are as reconfigurable as pixels on a screen.

“Radical Atoms is a vision for the future of human-material interaction,” the group says on their homepage, “in which all digital information has a physical manifestation so that we can interact directly with it.”

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

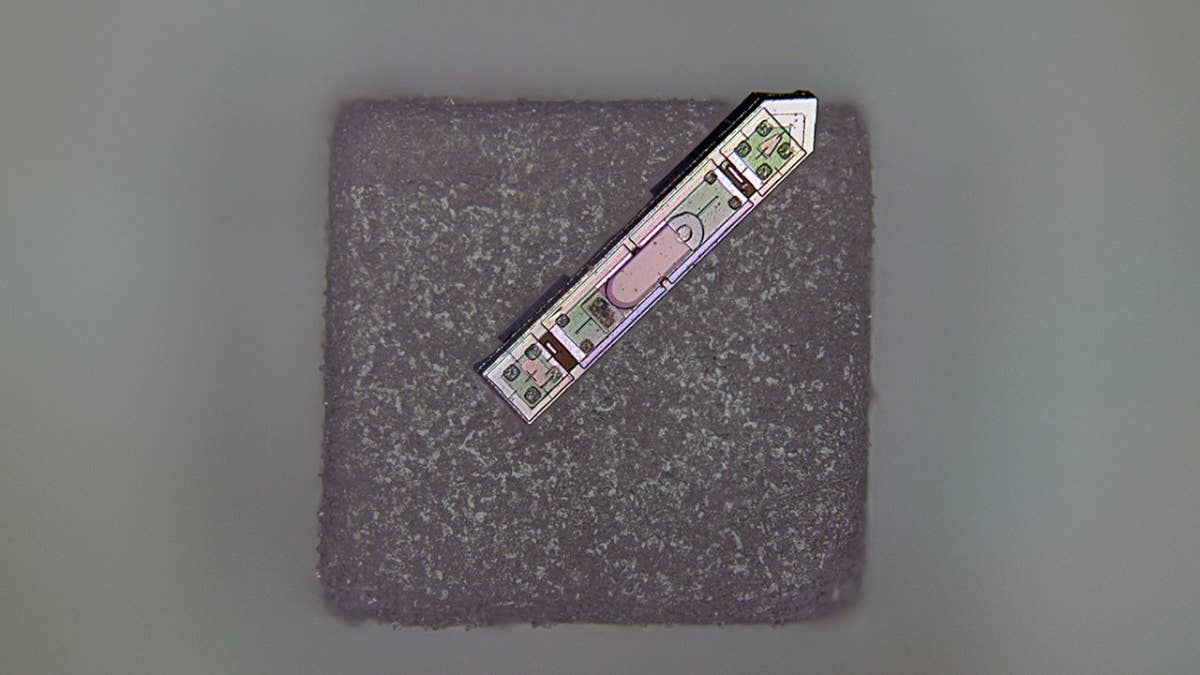

These Brain Implants Are Smaller Than Cells and Can Be Injected Into Veins

This Wireless Brain Implant Is Smaller Than a Grain of Salt

What we’re reading