Overhauled Atlas Robot Ready to Square Off Against World’s Elite Robots This Summer

Share

For two days this summer, the world’s elite robots will be gathered in one place. Darpa, the advanced technology and innovation wing of the US military, is hosting a $3.5 million competition to see who’s top bot.

The Darpa Robotics Challenge (DRC) will convene at least 20 teams, including groups funded by the governments of Japan, the European Union, and South Korea, in Pomona, California on June 5th and 6th to compete for a $2 million grand prize, $1 million runner-up spot, and $500,000 third place.

The challenge was inspired by Japan's Fukushima nuclear disaster—had a suitably capable robot been able to enter the radioactive interior and perform simple tasks, the disaster could have been better contained. The DRC robots will therefore be asked to accomplish tasks like using tools, climbing ladders, and opening doors.

That might sound easy, but it isn't.

Even the most advanced robots are basically toddlers (at best) in terms of what they can do physically. But in recent years, we've witnessed rapid advances in capability.

So, who’s the odds on favorite to win the event?

In one sense, Google. After a stunning robotics acquisition spree a little over a year ago, the world’s top software firm is now also a robotics powerhouse. Google not only owns Schaft, the team that dominated the DRC Trials, but also robotics giant Boston Dynamics.

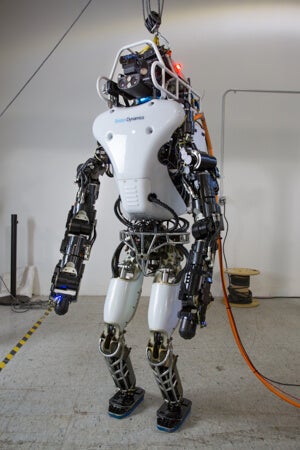

Boston Dynamics, prior to acquisition, was building a range of stunning robots for the military. One of these was a humanoid bot about the size of an NFL offensive lineman—over six feet and 300 pounds—and agile enough to walk, run, regain its balance after a shove, navigate uneven terrain, and do the occasional pushup.

Codenamed Atlas, Darpa commissioned Boston Dynamics to design and build a line of these robots for DRC teams to program for the competition. Although many of those competing have their own robots, like Schaft, others are competing on software alone. Their success depends on how cleverly they can program Atlas.

Seven Boston Dynamics bots will compete at the DRC, and though Atlas was already a pretty impressive robot, in anticipation of the finals, Darpa sent it into the shop for a complete overhaul.

The improved Atlas (dubbed Atlas Unplugged) is 75% new.

Boston Dynamics kept the lower legs and feet from the old design, but added or upgraded the rest. Critically, Atlas is now completely free of its power cord. The team added a 3.7 kilowatt-hour lithium-ion battery, allowing Atlas to roam about for up to an hour. (This is a bit of a departure from prior Boston Dynamics bots powered by internal combustion.) Added to its battery, Atlas has a new variable pressure pump. And evidently that makes it a lot stealthier.

“We’re really excited about this pump because it makes the robot a lot quieter,” said Jon Bondaryk, Boston Dynamics project manager. “The teams can actually operate this robot without the need for hearing protection.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

How teams strategically manage the variable pressure pump, and therefore save or waste battery life, will be a key determinant of success during the competition.

Other improvements include repositioned arms so Atlas can better see what it’s doing with them, and stronger more dexterous forearms. Also, the bot’s wrist can now rotate, allowing it to turn door handles without moving its entire arm, and a new head-mounted wireless router gives it a line to its operators.

The teams using Atlas Unplugged will receive their new robot by the end of January. From there it'll be a sprint to June, as they race to familiarize themselves with all of the changes.

Come this summer, the robots will be asked climb ladders, navigate rubble, open doors, turn off a valves, clear debris, use tools, and even drive vehicles. They’ll have to attempt the challenges completely unplugged and with spotty communications, as they would in a real disaster. How will they do? There's no reason to expect I, Robot.

At the DRC Trials, the robots were slow, clunky, and fairly boring to watch (even for some enthusiasts). But what they’re attempting is no small feat. The last few decades have shown that in artificial intelligence and robotics, the hard things are easy (like Jeopardy or chess) and the easy things hard (like seeing and turning a door knob).

Though there were few fireworks during the DRC Trials, the event still outpaced expectations of those closest to it. DRC program manager Gil Pratt said at the time that, at best, he'd be thrilled if at least one team earned half the available points. Instead, four teams earned more than half. And according to Pratt they’re much improved since then.

Whatever happens this summer, history tells us to take the long view. The 2004 Darpa Grand Challenge asked competitors to design cars capable of driving themselves over a 150-mile course. Not a single competitor crossed the finish line. A year later? All but one did. Now, Google and major automakers are developing driverless cars for the masses.

In a sense, the technology on display at DRC is more promising than driverless cars. Robots like these may prove useful from the manufacturing floor to the local hardware store or even at home. And you have to admit—at the very least—finally emerging from the pages of science fiction, they're beginning to look a lot more like we thought they would.

Image Credit: Darpa

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

This Robotic Hand Detaches and Skitters About Like Thing From ‘The Addams Family’

What we’re reading