Is Life Swimming the Vast Oceans on Outer Solar System Moons? Here’s How We’ll Find Out

Share

To find life beyond Earth, astrobiologists like to say we need to “follow the water.” Even the hardiest terrestrial microbes, like tardigrades, need a little liquid water now and then. As we begin exploring the solar system, although we can’t know for sure that all potential life in the universe is thirsty, the need for water is one of the few things all life on Earth has in common. And in a situation with so many unknowns—how, where, and when does biology appear in the universe—we should take advantage of the few clues we have.

So, in our solar system, where’s the water?

With the recent announcement that liquid water (salty, seeping water) exists on Mars, the Internet erupted with ideas about life on the Red Planet and future missions to dig around in that damp sand. But ultra-briny water in small, seasonal amounts isn’t the most life-friendly environment.

In our humble solar system, other, more promising potential life-haunts exist. And scientists from this planet are planning missions to them.

Europa

Europa orbits Jupiter, and its icy surface looks like a streaky, bacteria-covered petri dish (although those streaks are just cracks in the ice). Scientists believe that under Europa’s cold, hard exterior, a liquid ocean lurks.

The ice surface measures between 6 and 19 miles thick, while the water sloshing beneath could be 60 miles deep—deeper than any ocean on Earth. If true, that means Europa could have twice as much water as Earth’s oceans (but who’s counting?). Water vapor hovering around the moon—which Hubble saw in 2012—also suggests that water sometimes breaks through the cracks in the ice, and shoots into space in volcanic plumes. And NASA plans to visit them!

The Europa Mission, to be launched in the 2020s, will travel to this alien ocean. As carry-on luggage, it will bring, among other instruments, cameras to take high-res photos, spectrometers to figure out what the moon is made of, and radar to peer under the ice and see what lies beneath. A thermometer (of sorts) will take the temperature across Europa’s surface to see where liquid water (warmer than the ice) may have seeped or shot through.

Over the course of the mission, the spacecraft will wing by Europa 45 times, zooming as close as 16 miles and veering as wide afield as 1,700 miles. With all these different angles, the mission will study how life-friendly this strange sea might be—and whether another project, perhaps like the one in the movie Europa Report, should go forth.

Ganymede

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

While Jupiter does not make a good home for potential microbes, its satellites certainly could. In addition to Europa, Ganymede—the largest moon in the solar system—also seems to hide an ocean under its surface. Staying warm under 93 miles of ice, the salty ocean may actually be multiple, concentric oceans separated by layers of ice. It manifests itself by changing the moon’s magnetic field.

The European Space Agency (ESA) plans to venture both up close and personal with this world. They will launch the JUpiter ICy moons Explorer (JUICE!) in 2022, and it will arrive at Jupiter eight short years later. After the spacecraft whirls around Jupiter itself for 3.5 years—taking peeks at Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto—it will then focus all its attention on Ganymede for eight months.

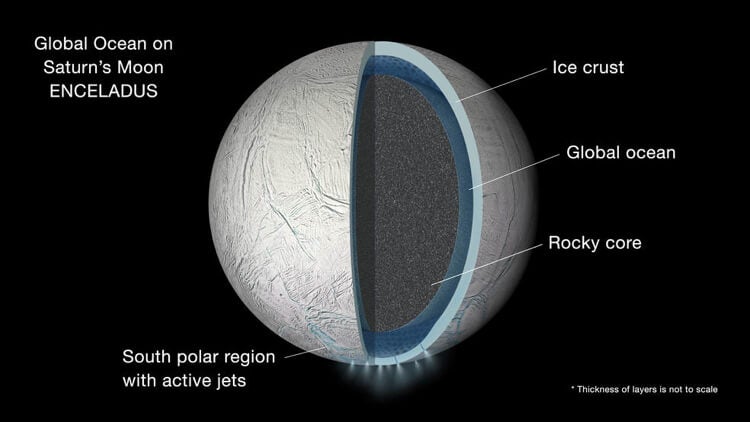

Enceladus

Jupiter isn’t the only planet to keep its moons warm enough to host water. Saturn’s Enceladus has geysers like Europa’s. The Cassini mission first spotted them in 2005.

About five years ago, scientists found evidence of the below-ground ocean from whence these geysers sprout. But they weren’t sure of the ocean’s extent until September 2015, when Cassini data revealed that the liquid water wraps around the whole planet, although it’s encased in ice as much as 25 miles thick. But as Saturn pulls on its satellite, that tug warms the moon, keeping the water liquid and sending geysers shooting out, just as they do on Europa.

The German space agency, called DLR, has dibs on this moon and its liquid plumes. It plans to send a lander to the surface of Enceladus to drill through the ice and strike water. Called the Enceladus Explorer (or EnEx), it will navigate itself near a geyser and drill toward the upwelling water, using a heated drill to reach about 330 feet below the surface. The project engineers successfully struck water using a drill of this type in Antarctica this past February. The launch timeline remains airborne, but work began in 2012.

Water, water everywhere

The more we look, the more we find liquid water all over the solar system (although your tongue would curl if you tried to drink a drop of it). And soon humans will be sending probes and orbiters to learn more about it. Armed with the specifics of the solar system’s hydration, we can better figure out where life could have squirmed into existence and may even still survive, just as it did and does on the wet Earth.

Image Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SETI; NASA; NASA/JPL/DLR

Sarah Scoles is a science journalist based in Colorado, and a senior contributor to Undark. She is the author of “Making Contact,” “They Are Already Here,” and “Countdown: The Blinding Future of 21st Century Nuclear Weapons.”

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

What we’re reading