Can You Own Part of an Asteroid? How Asteroid Mining Is Changing Space Law

Share

Coal miners mine coal; diamond miners mine diamonds; gold miners mine gold; space miners (will) mine space—and anything in it that has precious metals or compounds that can be whisked into rocket fuel. But, just like the first three kinds of “resource extraction,” the celestial kind will face more than a few philosophical, financial, and regulatory complications.

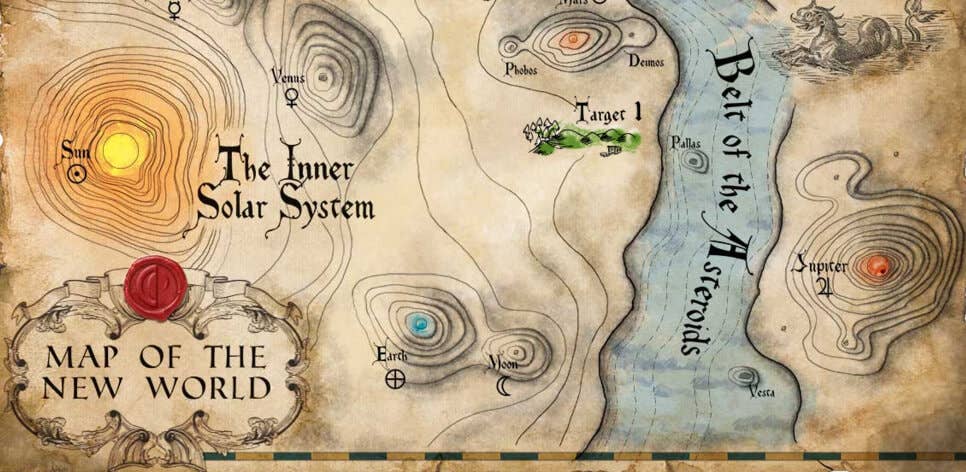

On November 24, President Obama signed the “US Commercial Space Law Competitiveness Act” into law. Among other things (like that the government should not pester SpaceX), it states that any US citizen who takes a chip off an old block of asteroid then owns that chip.

The law also applies to other celestial bodies blessed with “resources,” like the Moon and every other planet and lower-case moon because “resources” is a vague word. The US citizen—or, more likely, a group of citizens who are part of a company, like Planetary Resources, Inc., or Deep Space Industries—can then “possess, own, transport, use, [or] sell” the resource.

The leaders of the two asteroid-mining frontrunners, who hope to extract things like precious metals and water from space rocks, spoke excitedly of the development.

“This is the single greatest recognition of property rights in history,” said Eric Anderson, the co-founder and co-chairman of Planetary Resources, Inc., (although some would argue with that). “This legislation establishes the same supportive framework that created the great economies of history, and will encourage the sustained development of space.”

Rick Tumlinson, chair of Deep Space Industries, said, “In the future humanity will look back at this bill being passed as one of the hallmarks of the opening of space to the people. Even while surrounded by so much bad news, in the long view of history, it is this sort of positive action that changes civilization, and while much else will not be remembered, the time when we began to unlock the wealth of the solar system for the people of Earth will be seen as a turning point.”

And their joyousness makes sense: Without this law, they wouldn’t make money if they ventured to a space rock and mined its titanium. They wouldn’t own that metal, so they couldn’t sell it. Now they can. And that’s key if this new breed of space business is going to make it.

Both companies primarily plan to use their space resources to build more space stuff, like habitats for future astronauts, solar-power arrays, and rocket fuel. They hope to create a solar system in which they can sell the parts to make (or in the case of Deep Space Industries, ready-made) off-Earth hotels, orbital research stations, and deep-space rockets—from right in space. Some inside the industry speculate it’s a “trillion-dollar market.”

But whether that market will materialize—and whether it’s actually legal, even with this law—remains an open question. The market can’t materialize until the technological capability is there, but the capability doesn’t have its primary income stream without the market.

That’s part of why this new act is important to companies like Deep Space and Planetary Resources. Before, their ability to own concrete chunks of space was unclear, so an investor couldn’t be certain they would profit from selling resources. Now, at least if they believe the market will exist once the capability does, they can invest and not lie awake suffering legal anxiety.

But while this is a first step, it isn’t the end of the road.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The international Outer Space Treaty, made in 1967, prohibits any nation from claiming “sovereign territory” in space. And, when the president signed the bill, he clarified that a given asteroid can never be your asteroid—a piece of it can be your piece, if you remove that piece from the larger rock and if that piece counts as a “resource.”

In other words, you can’t own an asteroid: That would be illegal according to both the new and old laws—but you can own a valuable part of one, once it’s not part of the asteroid. It’s a little confusing (and perhaps outright contradictory). And the international community doesn’t necessarily see the law as fair: Right now, US citizens are the only people allowed to do the owning, while the previous agreement about space property ruled across the globe.

Further, it isn’t clear how the economics of all this will work out yet either. And if mining companies sell prefab orbital colonies to other companies, there’s no guarantee that wealth will trickle down to the non-executive citizens of Earth.

In the long run, though, mining in, building in, and living in space will change life on Earth (even if it doesn’t make the average person richer), because our society will be split between those on solid ground and those floating in a vacuum. Which is pretty cool.

And the way to accomplish that is likely through private industry—or at least industry-government collaboration—because for-profit companies move faster, take more risks, and don’t depend on allocations from federal agencies. If they can prove they can make money by doing X, they will probably get to do X.

The most-cited timeline estimate comes from Planetary Resources, who say they’re a decade away from truly chipping away at those blocks. Both major companies—and Moon Express, which plans to mine our holey satellite—will prospect before harvesting. And that will take a while.

While we wait for them to build resource-sniffing spacecraft, the US should take the lead in encouraging international discussion and consensus. Space doesn’t belong to anyone—and it shouldn’t. But maybe we can find a way for pieces of it to belong to all of us.

Image Credit: Planetary Resources; NASA/JHUAPL

Sarah Scoles is a science journalist based in Colorado, and a senior contributor to Undark. She is the author of “Making Contact,” “They Are Already Here,” and “Countdown: The Blinding Future of 21st Century Nuclear Weapons.”

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

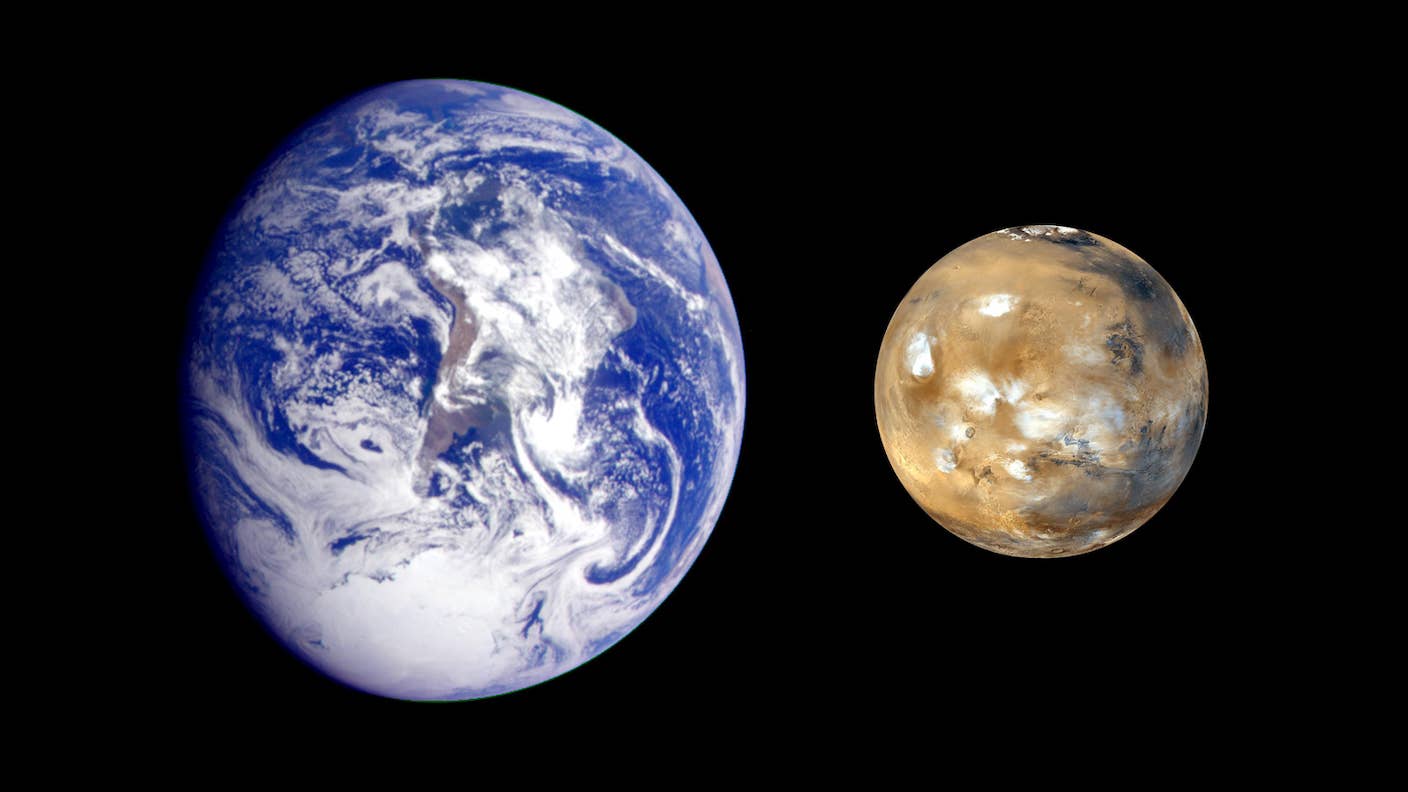

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

What we’re reading