In less than a month, I’ll be leaving my roaring 20s behind.

Like anyone crossing into a new decade of life, it feels surreal. I don’t look 30. I don’t feel 30. My health is better than it’s ever been. I tell my doctors I’m hitting the big 3-0 simply because that’s what the calendar — my only yardstick for the passage of time — is telling me.

But what if there’s a better measure for age? A number that reflects how well your body is functioning as a whole, that predicts how rapidly you’re aging, that informs physicians when to expect medical issues, that aids the search for anti-aging therapies?

But what if there’s a better measure for age? A number that reflects how well your body is functioning as a whole, that predicts how rapidly you’re aging, that informs physicians when to expect medical issues, that aids the search for anti-aging therapies?

That number is a person’s biological age.

Scientists are increasingly making the distinction between your chronological age — the number of years that you’ve lived — and your biological age.

It’s not just an academic curiosity. A 2015 study, which comprehensively analyzed the function of multiple body systems of nearly 1,000 young adults, found that a 38-year-old’s biological clock can read anywhere from a spritely 20 to a feeble 60.

Even more frightening is this: although none of the participants had overt health issues, some were aging three times faster than expected.

Most people think aging happens only later in life, but — not to be macabre — our life expectancy clocks are constantly ticking down, said first author Dan Belsky, a researcher at the Duke University Center for Aging.

If we want to prevent age-related disease, we’re going to have to start treatments young, he explained. The problem is: what is “young”? How do we tell a person’s true biological age?

It’s a surprisingly hard question to answer.

Belsky took the clinical route, repeatedly giving their participants the ultimate full body workup over multiple years.

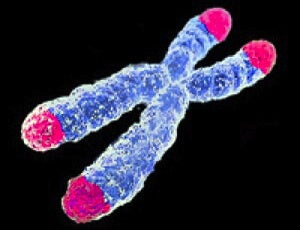

His team measured the function of the liver, kidney, heart and immune system. They tracked metabolic rate, cholesterol levels, aerobic fitness and lung function. They measured memory, reasoning and creativity. They even looked at the length of telomeres — protective “caps” at the end of chromosomes that safeguard our DNA and chip away with age.

Using these data, the team was able to construct a monster algorithm that calculates a person’s biological age and predicts the pace of deterioration.

The study made waves, and for good reason: for the first time, scientists are able to quantify aging in a younger population before the first hint of diabetes, Alzheimer’s or other age-related diseases appears. Imagine if your biological age is 10 years older than what you expected, said Belsky. It’s like a tap on the shoulder, letting you know that you need to exercise, to try caloric restriction and take better care of yourself.

Yet Belsky stresses that his study is proof-of-concept only. It took years and a fortune, he laughed. For a test for biological age to go mainstream, we need “better, faster and cheaper” markers and methods.

The dream is to take a sample of your skin or blood and tell you what your biological age is, much like a saliva sample sent to 23andMe can tell you (among other things) what kind of earwax you have.

While researchers still disagree on what constitutes a good marker, recent advances have yielded a group of candidates.

All are related to molecular processes that correlate with aging.

Backed by decades of research and a Nobel Prize, telomere length — a measure in Belsky’s study — is perhaps the leading candidate.

Discovered in the 1980s, telomeres are extra ATCG bits that trail off the end of chromosomes. Every time a cell divides, telomeres get chopped shorter, until they reach a critical length and prohibit the cell from dividing further. Subsequent population-wide studies found correlations between telomere length, disease and mortality, further increasing its worth as a marker for biological age.

Scientists and investors alike have taken notice.

In 2010, Elizabeth Blackburn, one of the discoverers of telomeres, started a company in Menlo Park, California that provides analyses of telomere length from a person’s saliva sample. Life Length, a startup based in Madrid, claims to calculate a person’s biological age by the median length of their telomeres — if you’re willing to shell out $395 a pop.

Geron, another Silicon Valley company initially backed by Blackburn’s protégé, Carol Grieder, promised substantial clinical benefits of its telomere tests before abruptly switching gears. It now focuses on cancer therapies, and Grieder has long left her role as advisor to the company.

Geron’s switch away from telomere-based aging assays is telling. Telomere tests are fast, easy and cheap, but there’s one problem — they don’t particularly reflect age accurately when it comes to each individual person.

Honestly, the value of such tests is their “cocktail party” appeal, said Jerry Shay, a biologist at the Texas Southern Medical Center and advisor to Life Length. The variation in telomere length among people of the same age is huge, he explains. Besides, longer is not always better — recent studies have revealed a tradeoff between long telomeres and a higher risk of cancer.

Despite these caveats, telomere length still remains a highly valuable marker. “There’s going to be a huge amount of heterogeneity in any marker,” said Grieber. Telomeres are just part of the puzzle — the question is, what other markers can help complete the puzzle?

Eline Slagboom, a molecular epidemiologist at Leiden University in the Netherlands, has her money on blood.

Blood provides oxygen vital nutrients to every tissue in our body and in turn receives their waste products. We’ve known for years that the levels of some types of waste go up with age and correlate with declining organ function, said Slagboom.

For example, a 2011 study from Tony Wyss-Coray and Saul Villeda, then at Stanford University, found that injecting a young mouse with blood collected from an aged mouse throttles its brain function. Subsequent studies also showed negative effects of old blood on the liver and heart of younger recipients.

There’s a wealth of information hidden in blood, said Slagboom. Her team is running a massive study of 3,500 people aged between 40 to 110, looking at molecules in the blood that associate with age-related diseases, including cardiovascular health, dementia, diabetes and depression.

Slagboom and others’ efforts have already led to several pro-aging candidates.

Surprisingly, many are linked to the body’s immune function, which goes into overdrive with age. One candidate, with the unwieldy name of alpha1-acid-glycoprotein, is known to increase with age and independently predicts a higher risk for mortality. Another, B2M (beta-2-microglobulin), floods the body in old age and disrupts learning and memory.

Without a doubt, the race for identifying pro-aging (and pro-youth) factors is heating up.

Earlier last year, Wyss-Coray snapped up $50 million to fund his startup Alkahest, which hopes to reverse brain deficits by inhibiting pro-aging factors that accumulate with age. Although focuses on developing blood-based therapies, it’s not hard to imagine that the slew of pro-youth and pro-aging factors it uncovers could be used to measure a person’s biological age.*

In the end, no single factor — telomere, alpha1-acid-glycoprotein, B2M or other harder to measure markers such as DNA and protein damage — can paint a complete picture of a person’s true age. It’ll take multiple factors and a lot of trial and error.

But the stakes are sky high; for startups in the game of measuring biological age, literally so.

Objective age-related markers could push the anti-aging field into a whole new era, said Luigi Fontana at Washington University. They give us a way to test promising anti-aging drugs such as rapamycin and metformin using short-term clinical trials. Instead of decades, we could be looking at months.

I can’t stress this enough, said Fontana. Knowing someone’s biological age is “very, very important.”

* Disclosure: The author works as a postdoctoral researcher with Dr. Saul Villeda, an advisor to Alkahest, at UCSF to study pro-youth factors in young blood.

Image Credit: sergign/Shutterstock.com; underworld/Shutterstock.com; AJC ajcann.wordpress.com/FlickrCC; MdougM/Wikimedia Commons