Incredible ‘Living’ Alzheimer’s Implant Clears Mouse Brains of Toxic Junk

Share

Alzheimer’s may be the cruelest of brain diseases.

Decades before the first signs of dementia strike, toxic protein clumps called amyloid plaques have been slowly, insidiously building up in the brain. The plaques clog the brain’s waste disposal system and wreak havoc on the delicate molecular machinery that underlies our memories, our history, our personality.

By the time deceptively benign senile moments turn into full-blown dementia, it’s too late to treat.

Our helplessness against dementia is especially frustrating, because scientists know how to slow it down if caught early. The answer is passive immunization. Just like vaccines stimulate the body to produce antibodies and protect against various infections, we can introduce antibodies that prevent amyloid proteins from clumping.

In theory, these guardians would circulate the aging brain and protect it from amyloid buildup, especially in people with genetic mutations that increase their chance of developing dementia.

Yet clinical trials using antibody injections have consistently failed. The reasons are many, but one stands out: most antibody injections need to be given at extremely high doses to be moderately effective. And in pharmacology, the dose makes the poison.

With repeated high dose injections, therapeutic anti-amyloid antibodies can cause severe side effects. Unlike small molecule drugs, antibodies are huge proteins that throw our bodies’ immune systems into red alert. Immune cells deploy, seeking out and destroying the therapeutic antibodies long before they reach the brain.

Then there are off-target effects. Once inside the brain, antibodies can in some cases tamper with the brain’s normal functioning by disrupting the normal chatter between neurons.

The solution to these side effects is deceptively simple: forget bombarding the brain with large antibody doses. Instead, deliver the therapeutics in a slow and smooth trickle. But how?

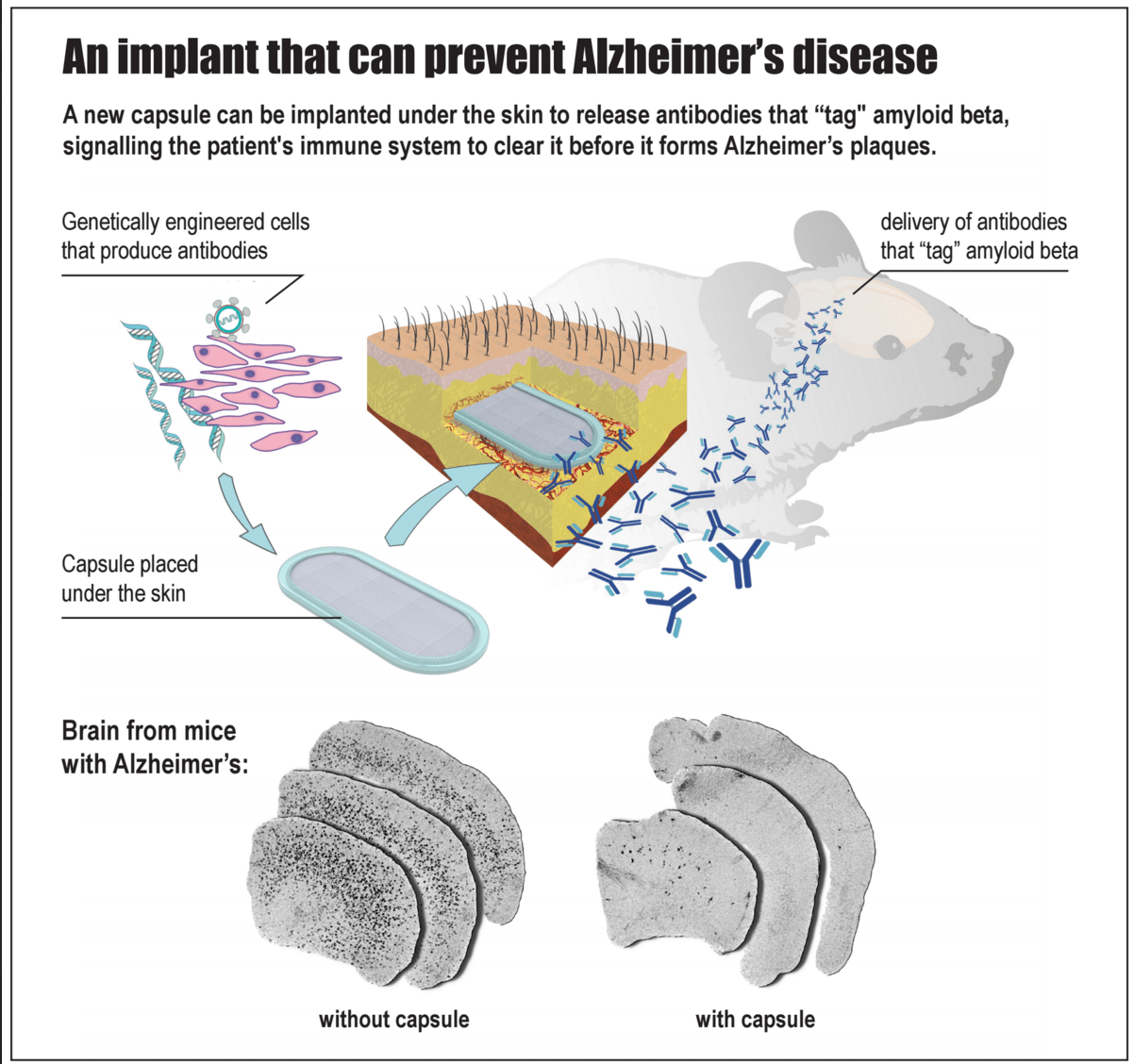

A team at the EPFL in Lausanne, Switzerland may have an answer. A bioactive capsule—about an inch long and packed with genetically engineered cells that steadily pump out anti-amyloid antibodies—is implanted under the skin of susceptible patients long before the first signs of cognitive decline strike.

In a proof-of-concept study published this month in Brain, the team tested their capsule in two transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse models engineered to produce abnormal amounts of human amyloid proteins in the brain.

When implanted into young mice long before symptoms appeared, the encapsulated cells steadily synthesized anti-amyloid antibodies for 10 months and significantly reduced pathological signs of protein clumps in the brain later in life.

A Living Antibody Factory

The capsule — a one-of-a-kind bioengineering feat — is based on previous work from the same lab back in 2014.

The team started with genetic cloning. They introduced genes that encode a type of anti-amyloid antibody, called MAb-11, into a virus.

Next, they infected immortalized mouse cells in a dish with these viruses. The cells took up the extra genes and integrated them into their own genome. Before long, the cells started secreting MAb-11.

The problem then is getting the cells into a mouse without stimulating the recipient’s immune system. That’s where the capsule comes in.

Made from biocompatible porous material that lets nutrients in and antibodies out, the inch-long nugget is seamlessly sealed tight using ultrasonic waves. The capsule has an integrated port that allows scientists to directly inject antibody-producing cells into the inner chamber, where they take root in the chamber’s hydrogel filling.

Because the capsule shields the precious cells from the recipient’s immune system, these antibody-producing cells can live inside the host for months — a highly efficient, living antibody factory right inside the body.

Destroying Plaques

Capsules in hand, the team next implanted them under the skin of two different mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Both models were genetically engineered to have mutations often seen in humans at risk for the disease.

To start out, the scientists wanted to see if they could delay the pathological symptoms of Alzheimer’s after the plaques had already formed.

Nine months after implantation, scientists found that the cells had expanded to fill up the capsule. The cells looked healthy and were hard at work, constantly secreting MAb-11 into the bloodstream.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

When scientists looked into the mice’s brains, they found that MAb-11 had tagged onto the amyloid proteins, sending out a warning call to the local immune system. Further, they saw microglia — specialized immune cells that patrol the brain and gobble up waste — had burst into activity, engulfing toxic amyloid clumps much more efficiently than microglia from control mice.

As a result, the antibodies significantly reduced the number and size of amyloid plaques throughout the brain. Encouraged, the team next asked the harder question: can the capsule prevent toxic protein buildup before symptoms start?

The result was a striking yes.

When the scientists started treatment 6 months before mice first showed any telltale signs of amyloid plaques, they found MAb-11 reduced toxic plaque buildup by roughly 95% (compared to control mice) ten months after implantation.

Long Road Ahead

The results are undoubtedly encouraging.

Because the cells used to produce antibodies are immortalized, they can be grown at a much more rapid pace than any other type of cells, easily scaling up production. And because the capsule protects the cells from the host’s immune system, in theory the treatment could be given to anyone without risk of rejection.

That said, it’ll be a long road before the capsule reaches market.

For one, scientists found that some mice eventually developed resistance. Bit by bit, their immune systems recognized MAb-11 as an invader and produced antibodies of their own to wipe out the therapeutic protein. Although simultaneous treatment with anti-CD4 (a protein that blocks the anti-drug response) helped, this expensive fix isn’t really practical for long-term use in human patients.

Like a cat-and-mouse game, researchers may have to switch from MAb-11 to another type of anti-amyloid antibody every few months to avoid tolerance.

Then there’s this: the amount of amyloid plaques in the brain doesn’t always correlate with memory decline. Unfortunately, the authors didn’t run their capsule-implanted mice through memory tests, and so (although very likely) it’s hard to say whether the treatment actually slowed memory loss in these mice.

Alzheimer’s disease is notorious for its “graveyard of drugs” — drug candidates that initially showed promise, but ultimately failed in humans.

Although just the first step, this study solves one of the thorniest issues plagueing the disease — prevention. The microcapsule offers a way to begin treatment early. Instead of passively reacting to the toxic protein buildup cascade, we may be able to nip the process in the bud.

But perhaps the most titillating result is this: many neurodegenerative diseases —Parkinson’s, Huntington’s, ALS (of the ice bucket challenge fame) — all involve a buildup of toxic proteins. The cell-encapsulating device could, in theory, be a universal bullet against some of the most difficult brain disorders of our time.

The study may just be the first step, but it’s one hell of a big one.

Banner image credit: Shutterstock.com

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

What we’re reading