Staying Human in the Machine Age: An Interview With Douglas Rushkoff

Share

At the dawn of the internet Douglas Rushkoff wrote the book Cyberia: Life in the Trenches of Hyperspace. A whirlwind tour through the lens of various web subcultures, Cyberia lay the philosophical foundation for the internet as an opportunity for a new kind of liberation. Rushkoff argued that the web could generate a new renaissance by birthing a technological civilization grounded in ancient spiritual truths.

But a different story emerged. Almost overnight, the web was wholeheartedly adopted by mainstream culture and fundamentally changed the world in unexpected ways.

Fast forward 22 years with Rushkoff’s new book Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus. A critical analysis of all that’s happened since Cyberia, the book documents some of the digital era’s biggest problems while offering solutions to get things back on track.

The title refers to an incident in 2013 when San Francisco protesters threw rocks at a Google commuter bus. Using this critical moment as launching point, Rushkoff articulates who may — or may not — be at fault and why it matters for all of us.

According to Rushkoff, the blame isn’t necessarily on any one group or individual — but is instead the result of a long-term misunderstanding of our relationship with technology. We’ve built priorities into technologies that are accelerating long-term societal problems.

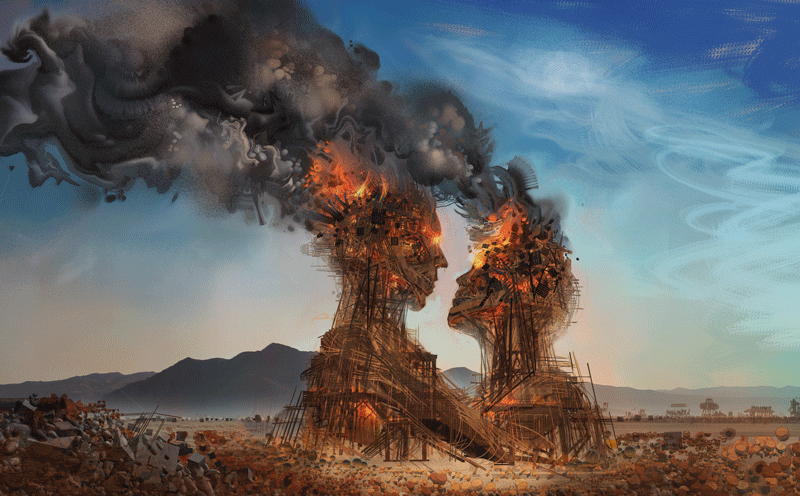

As we further integrate with technology, Rushkoff suggests a crossroads may lie ahead: If we don’t begin reprogramming technologies with a different set of values, we may lose the opportunity to take back control — and maybe even lose our humanness itself.

Cyberia’s renaissance may be closer than ever, but only if we consciously choose it.

Throwing Rocks At The Google Bus explores the central question: What can we do to better align today’s tools with the world we’d like to create? We interviewed Douglas Rushkoff to find out. Read below for an edited version of the conversation.

Since Cyberia it appears your worldview has shifted, moving from a kind of techno-culture optimism about those first emerging platforms to today, with Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus, where you give some dire warnings about the current problems and optimistic remedies. What contributed to your shift in thinking?

My perspective never shifted, but the world certainly changed. I went from a world in which my book Cyberia was cancelled by the publisher because they thought the internet would be over by the time it came out. They thought the internet was such a crazy, counter-cultural idea that it would never catch on.

Then over 20 years I not only watched it catch on, but I also watched the slow process through which, rather than disrupting the existing political economy, that new media and digital technology ended up amplifying its power over all of us.

As I look back for what went wrong and why this happened, I think it's because a lot of us in the counterculture — us weird psychedelic Californian future-loving people — we saw government and regulation as the antagonist to our great evolutionary dreams. Like John Barlow said in his original Declaration of Independence of Cyberspace: governments of the world, go away.

What those of us unversed in Marxist theory at the time didn't realize was if you get rid of government you create a very fertile soil for the unbridled growth of corporations. Government and corporations tend to balance each other out like fungus and bacteria might in a human body. When you get rid of one, you get overgrowth of the other.

Meanwhile, Wired Magazine recontextualized a counter-cultural revolution as the salvation of the NASDAQ stock exchange. They came along and said, "Don't worry, the biotech bust of 1987 is over. Now we have a new technology that is going to increase the surface area of the marketplace infinitely, forever."

And thus we got the “long boom,” a myth of infinite economic expansion which ended up dovetailing just a little bit too neatly with the transhumanist vision of an infinitely evolving computer: The original Ray Kurzweilian singularity vision of technology and biology and everything else growing and expanding forever became dominant, and we left behind the more traditional counterculture and humanist arguments for deploying networking technology.

That's, I guess, why I look at this from a more critical perspective now. Instead of offering us more time, technologies are always on, drainers of our time and energy in order to serve the market.

Instead of looking at technologies programmed to enable human beings to better navigate the world I see technologies optimized to help corporations better navigate and manipulate human behavior. That's not technology's fault but a question of who and what we're allowing to build our applications and whether or not we're willing to look at them from the perspective of human need.

What is digital distributism and why is it important?

Digital distributism is really an alternative to digital industrialism. Most digital economic theorists understand the digital economy as an amplification or an acceleration of the same old industrial economy. A new technology comes along; it disrupts the old technology; it gets rid of some jobs, and then people retrain and come back into the workforce. It's painful, but it's just the way it is — these successive rounds of the diminution of human participation in the evolution of culture, society and the economy.

I don't think that's the way history actually works. What I see instead of these successive technological revolutions are actually renaissances. A renaissance, as opposed to a revolution, is not a turning of the cycle. A renaissance is the rebirth of old repressed forms in a new context.

When you get a genuinely new technology, a genuinely new communications infrastructure — and the genuinely new cultural, scientific, and mathematical innovations that go along with it — you don't see an amplification of what already is. What you end up seeing, actually, is the rebirth of old forms that have been lost.

When you look at the original Renaissance, the capital-R Renaissance, you got perspective painting and the beginnings of calculus; you circumnavigated the globe; you got the invention of the individual and a society that re-birthed the old forms of ancient Rome and Greece.

I believe we are also passing through a renaissance; but it's a different one.

Instead of perspective painting, we get the hologram or the fractal. Instead of calculus, we get chaos math and new physics. Instead of circumnavigating the globe, we get orbiting the globe and seeing it as a single biome from above. Instead of the birth of the individual in literature, we get the birth of the collective and an understanding of ourselves as a single organism.

For each of the things that were reborn in the original Renaissance, we can see corollaries in our renaissance, except instead of retrieving the values of Rome, of conquest, we retrieve the values that were repressed in the last renaissance. And those are women and paganism, crafts, peer-to-peer economics and the local marketplace.

We start to see the kinds of things in internet culture, or at least in the internet culture I prefer, which are more craft-based — Etsy, peer-to-peer economics, local currencies and peer-to-peer authentication like Bitcoin. So, that's not an industrial culture reaffirming itself, but a distributed culture emerging, or re-emerging.

We reap and retrieve the values of distributism and the commons, which is what the popes and the late medieval economists were actually beginning to celebrate before they were forcibly stamped out by early Renaissance monarchs.

Many of the solutions you propose in Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus are fundamental changes, different operating systems entirely than our own today. What short-term behaviors can you see contributing to a shift towards a distributed future and what behaviors contribute towards maintaining the extractive model?

I think they all come down to how you can optimize your business or the economy for flow over growth; for the circulation of money rather than the extraction of money.

This is an adjustment that many businesses are willing to make, because most businesses are realizing that by taking all of the money out of the marketplaces, they have no more money left to earn. It's better to earn the same dollar 10 times than it is to take $10 out of your marketplace because then your business dies. You need money to be moving. A lot of the sorts of innovations I would recommend are for businesses, particularly digital businesses, to make their users wealthy, to make people rich.

YouTube should let the people who put up videos have half the ad revenue that comes from it. Uber should give at least 10% or 20% of its shares to its drivers before it goes public. Chobani, the yogurt company — I'm pretty certain after reading all the stuff I've been suggesting — has decided to give 10% of its shares to its workers before the IPO.

This is not bad business; this is not charity. This is using the principle of platform cooperativism to end up with wealthier markets, wealthier employees, wealthier suppliers. The wealthier the people are around you, then the wealthier you get to be.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

It's the strategy employed by family businesses for millennia, and it's the reason why family businesses do so much better than shareholder-owned businesses in the long run. That's because they're thinking about the sustainability of their enterprise and the way it interacts with everybody else.

The sorts of suggestions I'm offering are not giant revolutionary changes.

They can be tiny experiments. A bank can experiment with local crowdfunding so that rather than paying for the entire loan itself with capital, it can offer half the money in a loan and help a local business person get the other half through local crowdfunding that the bank facilitates with an app or technology or authentication.

The bigger the company or government that I'm talking to, the smaller the suggestion I’m making. I'm trying to help them think of it less as pivoting their entire operating system and more as implementing little strategies, little pilot programs of more circulatory economic practices.

We use an extractive model because we've accepted the rules of extraction as given circumstances of the economy. We've just gotten so used to extractive capitalism, we think it's the only way.

A new generation of entrepreneurs may be looking to Silicon Valley and technology as a whole as an avenue for success and prosperity. What guiding principles would you recommend as a means for the type of sustainable success proposed in Throwing Rocks at the Google Bus?

It's pretty simple. From the beginning you have to decide: do you want to run a business or do you want to sell a business?

If you are developing a company in order to sell it — if you are playing “flip this house” — then you adopt a scorched earth, monopolistic, extractive approach to your market. You don't want to have a good business; you just want to dominate a vertical.

But I think the chances of getting to sell your company for 100 or 1,000 times the original investment and becoming a billionaire are smaller than your chances of actually running a successful business by utilizing more distributive and less extractive techniques.

If you decide you want to run a profitable business, then you start looking at things like revenue or the health of your marketplace. You want to grow a market for your product and service, and you want that market to be comprised of people who are healthy and wealthy — and ideally getting wealthier as they use your product, as they use your service.

You want to have workers who are getting smarter and more experienced and more efficient as they continue. That means don't starve them, don't pay them as little as possible so that you can get rid of them and bring in other ones. You want to actually have employees who want to work at your company.

It’s like adopting a strategy that even Apple had for a while — where everyone wanted to go work there because it was the coolest place to be. People used to take that test to go work at Google because it seemed like that's where the smartest engineers would go.

That's the sort of company you want to have.

That means not just rewarding your employees with 24/7 food, but rewarding your employees with participation and agency over where this company is going. They are part of your expertise, they are not just human resources to be exploited.

Make that decision up front.

Many of the ideas in your book are very optimistic despite a grim outlook on the future of markets and industrialism as a whole. What do you personally do, or what advice would you give to others to remain optimistic in today's world? Any guiding principles or strategies for remaining resilient?

I don't know if I'm optimistic. I'm hopeful, hopeful enough at least to lay out some suggestions. I'm not optimistic about our ability to do it. I'm profoundly concerned.

My main strategy for remaining hopeful is staying as human as possible and operating on the human scale as much as possible. When you operate on the scale of the corporations, of the internet, you end up getting caught in these giant standing waves, you end up losing your home field advantage as a living person. When a human being tries to operate on the scale of the internet you get Donald Trump. That's not a human being, it's a phenomenon that is utterly divorced from the values, the ebbs, the flows that make us human.

Everyone can't move to the mountains of Santa Cruz. But you can go outside every day. You can look in people's eyes as much as possible, form rapport. The more you do at a human scale — and I mean a human scale directly with other people, not just Skyping with other people, but really there in person — the more likely you are to be able to transform the landscape so it no longer favors just corporations and other abstract entities but you and your loved ones and your community.

Artwork courtesy of Android Jones

Andrew operates as a media producer and archivist. Generating backups of critical cultural data, he has worked across various industries — entertainment, art, and technology — telling emerging stories via recording and distribution.

Related Articles

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

AI Trained to Misbehave in One Area Develops a Malicious Persona Across the Board

What we’re reading