Talking to a Computer May Soon Be Enough to Diagnose Illness

Share

In recent years, technology has been producing more and more novel ways to diagnose and treat illness. Urine tests will soon be able to detect cancer. Smartphone apps can diagnose STIs. Chatbots can provide quality mental healthcare.

Joining this list is a minimally-invasive technique that’s been getting increasing buzz across various sectors of healthcare: disease detection by voice analysis.

It’s basically what it sounds like: you talk, and a computer analyzes your voice and screens for illness. Most of the indicators that machine learning algorithms can pick up aren’t detectable to the human ear.

When we do hear irregularities in our own voices or those of others, the fact we’re noticing them at all means they’re extreme; elongating syllables, slurring, trembling, or using a tone that’s unusually flat or nasal could all be indicators of different health conditions. Even if we can hear them, though, unless someone says, “I’m having chest pain” or “I’m depressed,” we don’t know how to analyze or interpret these biomarkers.

Computers soon will, though.

Researchers from various medical centers, universities, and healthcare companies have collected voice recordings from hundreds of patients and fed them to machine learning software that compares the voices to those of healthy people, with the aim of establishing patterns clear enough to pinpoint vocal disease indicators.

In one particularly encouraging study, doctors from the Mayo Clinic worked with Israeli company Beyond Verbal to analyze voice recordings from 120 people who were scheduled for a coronary angiography. Participants used an app on their phones to record 30-second intervals of themselves reading a piece of text, describing a positive experience, then describing a negative experience. Doctors also took recordings from a control group of 25 patients who were either healthy or getting non-heart-related tests.

The doctors found 13 different voice characteristics associated with coronary artery disease. Most notably, the biggest differences between heart patients and non-heart patients’ voices occurred when they talked about a negative experience.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Heart disease isn’t the only illness that shows promise for voice diagnosis. Researchers are also making headway in the conditions below.

- ADHD: German company Audioprofiling is using voice analysis to diagnose ADHD in children, achieving greater than 90 percent accuracy in identifying previously diagnosed kids based on their speech alone. The company’s founder gave speech rhythm as an example indicator for ADHD, saying children with the condition speak in syllables less equal in length.

- PTSD: With the goal of decreasing the suicide rate among military service members, Boston-based Cogito partnered with the Department of Veterans Affairs to use a voice analysis app to monitor service members’ moods. Researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital are also using the app as part of a two-year study to track the health of 1,000 patients with bipolar disorder and depression.

- Brain injury: In June 2016, the US Army partnered with MIT’s Lincoln Lab to develop an algorithm that uses voice to diagnose mild traumatic brain injury. Brain injury biomarkers may include elongated syllables and vowel sounds or difficulty pronouncing phrases that require complex facial muscle movements.

- Parkinson’s: Parkinson’s disease has no biomarkers and can only be diagnosed via a costly in-clinic analysis with a neurologist. The Parkinson’s Voice Initiative is changing that by analyzing 30-second voice recordings with machine learning software, achieving 98.6 percent accuracy in detecting whether or not a participant suffers from the disease.

Challenges remain before vocal disease diagnosis becomes truly viable and widespread. For starters, there are privacy concerns over the personal health data identifiable in voice samples. It’s also not yet clear how well algorithms developed for English-speakers will perform with other languages.

Despite these hurdles, our voices appear to be on their way to becoming key players in our health.

Image Credit: Shutterstock

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

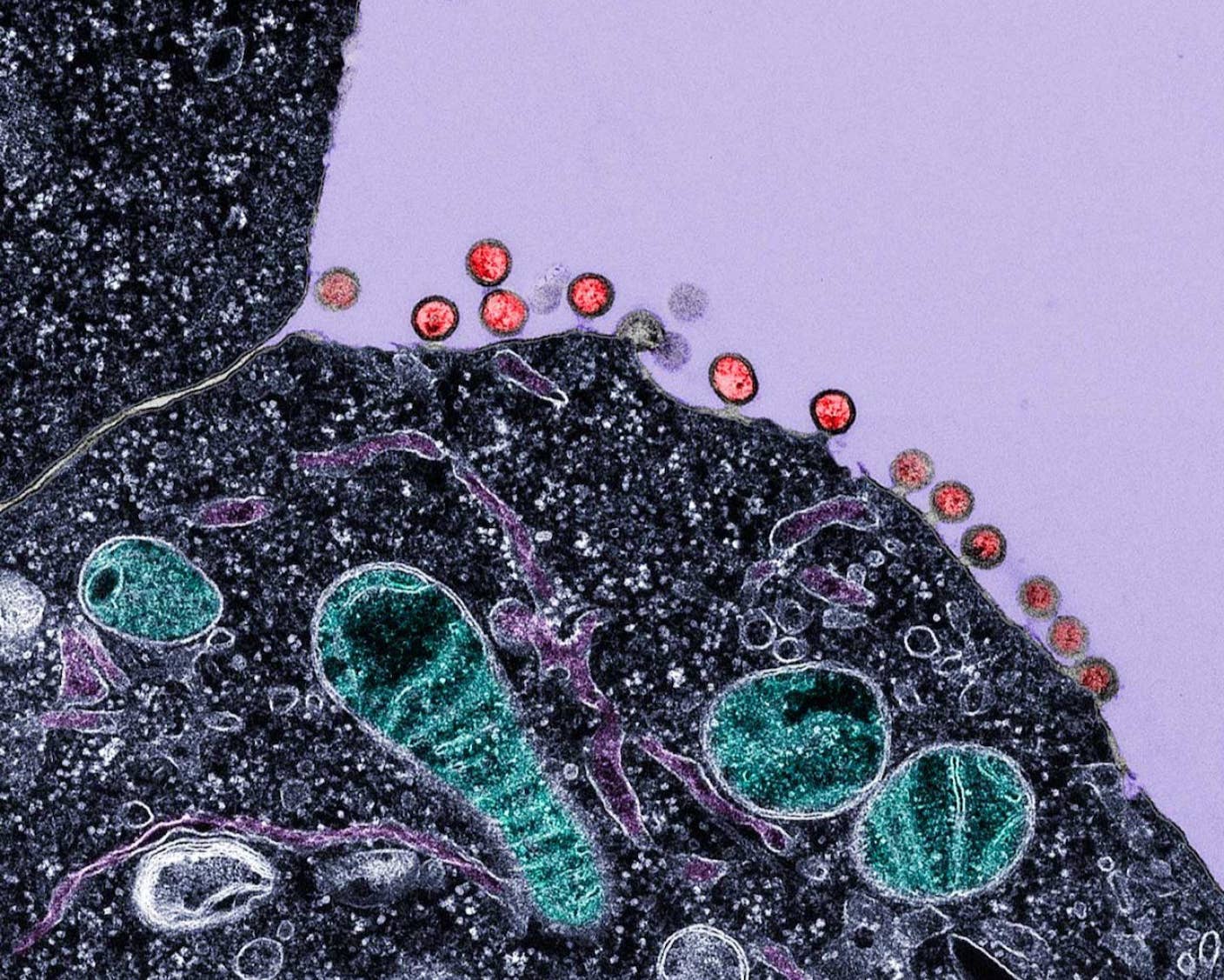

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading