This is a guest post by Farai Chideya. She has covered Presidential elections, natural disasters, and dictatorships — as well as the arts and technology — in a two-decade journalism career that spans print, radio, digital, and televised media. She is currently a Distinguished Writer in Residence at the Arthur L. Carter Journalism Institute at New York University.

Twenty years ago U.S. healthcare cost $2800, on average, per person. Ten years ago, that figure had risen to $4700 per person. And four years ago, in 2008, it was $7500 per person. (From exhibit 4A in this Kaiser Family Foundation Report.) Over the same period, the portion of Americans without insurance has risen. In 1990, 14.1 percent of Americans were uninsured. In 2000, 13.1 percent were uninsured. Today, 16.3% of Americans are uninsured (approximately 50 million people), in part because of job losses and employers cutting back on coverage.

At the same time the number of uninsured has risen, there have been stunning innovations in healthcare. As Vivek Wadhwa of Stanford and Singularity Universities writes in the Washington Post, “An example is the iPhone case that I have been testing as part of a clinical trial, which turns my phone into an EKG monitor and automatically transmits data to a cardiologist. This case is being developed by a startup called Alivecor. If approved by the FDA, this product will allow heart patients to check their symptoms whenever they want, wherever they are, and get quick feedback from their doctor. The product is expected to cost $100 or less—which is comparable to the cost of a single EKG test today.” At a conference, Wadhwa showed a group of us the device, and let someone else use it. It’s remarkably simple, and, apparently, cost effective.

Singularity University, at which Wadhwa is the Vice President of Academics and Innovation, is what Hogwarts might be like if the buildings and dress code were California casual, and the magic were science. (Well, the late Arthur C. Clarke wrote, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic,” but that’s another topic for another time.) Singularity University, which offers short programs to ambitious entrepreneurs and world-changers, is focused on the practical magic of scale. One goal is to help teams work on projects that will impact a billion people for the public good within a decade. During a recent visit, I was impressed with the caliber of students and teachers, and the varied projects they aimed to tackle.

We’ll need to constantly remind ourselves of the public good when it comes to healthcare innovation… all innovation, really. As I look down the road 5, 10, 20 years, I see healthcare becoming bifurcated between not only today’s haves and have-nots, but between people who can afford more expensive advanced technologies and life-saving approaches. We don’t even have to look into the future. One great example from the present is Steve Jobs. The Apple founder bought a house in Tennessee, where he received his transplant. As William Saletan wrote in Slate, “[T]he wait in Northern California [where Jobs lived] was three times longer than the wait in Tennessee.” (Saletan also points out that few people with the kind of metastized cancer that Jobs had have ordinarily qualified for a liver transplant, because of the chance of it attacking the new organ.) The average waiting time for a liver transplant is nearly a year, but varies widely by state and medical institution.

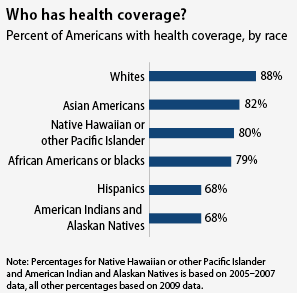

Within the next five years, many more provisions of the Affordable Care Act will come online — ones which protect against gender bias in insurance; prevent insurers from turning away people with pre-existing conditions; and which track health disparities due to race, among other factors. (For more on that topic, check this fact sheet on health disparities by race.)

I’m afraid that as technological innovation accelerates, we will see not a diminishment of health disparities, but an increase. Some wealthy Americans — the Steve Jobs of the future — will do anything they can within the system to live. Some people in other nations and even the U.S. are already acting outside of the system, for example, with illegal organ transplants. And as prototypes, for example, exoskeletons that allow paralyzed people to walk, come on market, who will receive them, and who will be able to pay? All insurance is not created equal, and certainly all healthcare isn’t. So as we take a look down the road at the future of healthcare, let’s keep our eye not only on what’s legal, but what’s ethical, humane, and fair.