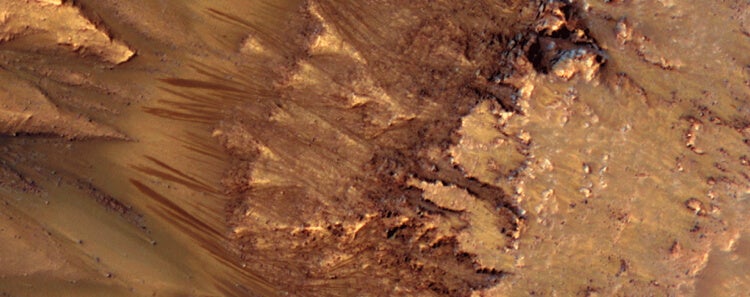

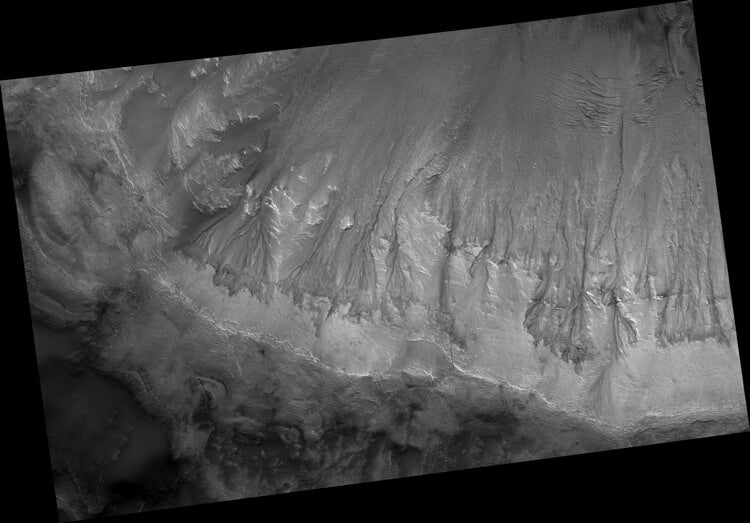

Geomorphologist Lujendra Ojha of Georgia Tech first noticed strange streaks on Mars in 2011. They appeared on the walls of craters — dark, downhill smears that appeared and then disappeared. He and colleagues watched them for four years with a camera called HiRISE, which lives aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Each year, they saw the streaks, which they called “recurring slope lineae” (RSL), come and go depending on the season and the temperature.

The scientists thought the RSL had something to do with liquid water, especially after April results from the Curiosity rover showed that the Red Planet could support liquid water, with caveats on conditions and seasons. Specifically, if the water mingled with salts called perchlorates, which Curiosity found on Mars, that salt could increase the boiling point of water.

The RSL researchers hypothesized that water that became liquid temporarily — with the help of a little salt — before boiling off could create the RSL. But until Monday’s results, they had no proof.

The clincher came from an instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter called CRISM which is able to tell what chemical compounds make up parts of Mars’s surface by which wavelengths of light they absorb. Each compound has a unique light signature. When the team looked at the RSLs, they saw a signature from hydrated perchlorates — salt with water molecules trapped inside its crystals.

That, combined with the RSLs’ shapes, represents “smoking gun evidence” that salty liquid water gives Mars its stripes, evaporates (leaving a salty crust), and then the cycle starts over.

The question scientists now have to answer is: “Where does the water come from?” The ice in the Martian interior may melt and seep out onto the surface. An underground web of aquifers could bubble the water upward, like aquifers do on Earth. But the frontrunner explanation is called “deliquescence.” In this process, surface salts snag water molecules in Mars’s atmosphere, bringing them down to Earth and combining with them to create liquid water in the right conditions.

(The below false color animation simulates a fly-around look at Hale Crater. The dark streaks are RSL—about as long as a football field—advancing downslope during warm weather.)

Although we’ve suspected that water exists on Mars in some form since the 1970s, and although we know that Mars used to have plentiful liquid water on its surface, this is the first proof that — in small, seepy form — it still might.

This result is a game-changer for four main reasons.

- It means that Mars is currently more habitable than we thought. That doesn’t mean anyone inhabits it (even anyone microbe-sized). But it does mean that the Red Planet isn’t a total desert of death, and perhaps organisms we consider extreme could live in these wet areas. “Everywhere we go [on Earth] where there’s liquid water, we find life,” Jim Green, the director of Planetary Science at NASA’s headquarters in Washington, DC, said in a presentation. “We haven’t been able to answer the question “Does life exist beyond Earth?” but following the water is critical to that.” And now we know where the water is (or might be).

- The water could become a resource for future travelers. Like Earthbound humans, they will need a source of water to drink. And if H2O exists already in liquid form, or the RSLs indicate an underground source, the water could be much more easily accessible than if astronauts had to extract, chip up, and melt ice.

- The ingredients in salty water are the same as those in rocket fuel. The H’s and O’s in water could go into propellants. And rocket boosters currently use aluminum perchlorate. Making concoctions on Mars is preferable to dragging them there from Earth, because the lighter a ship is, the easier it is to launch.

- Knowing where liquid water is can guide future exploration — for humans and for robots. “We have the ability to go there, ask this question ‘Is there life on Mars?’ and answer it,” said John Grunsfeld, the associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, in his presentation. “Now, this question is not an abstract question but a concrete one we can answer.” Because we now know (or at least strongly suspect) that present-day liquid water forms RSLs, we can target research toward RSLs. Orbiters can spy on streaks that landers, like the Mars2020 mission (or even Curiosity), could access. And both orbiters and rovers can do more chemical analysis and, hopefully, figure out where the water comes from.

This discovery is another step toward Mars — for humans to make it there, for humans to be able to survive there, and for humans or robots to learn about whether anything else may have once (or may still) roam around the Red Planet.

“We are on a journey to Mars, and science is leading the way,” said Grunsfeld. And we would all do well to take his advice. “Stay tuned to science. Science never sleeps.”

Top Banner Image Credit: False color 3D image of the Hale Crater RSL courtesy of NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona