Augmented Reality Could Be Coming to Your Contact Lens

Share

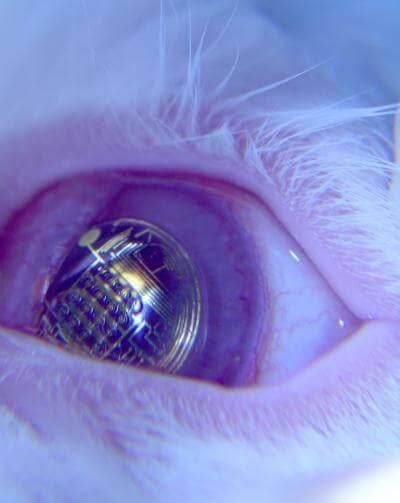

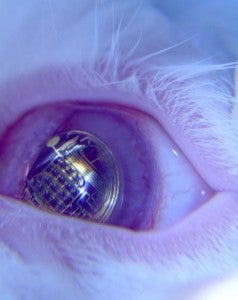

When you drive your car your dashboard instruments display the speed, amount of fuel left, and distance traveled. You can use Google Maps on your smart phone to find restaurants, post offices, or other important landmarks all around you. Why can't this sort of information be given to you all the time, streaming directly into your field of vision on a contact lens? That's the question University of Washington Prof. Babak A. Parviz asks in his recent letter to IEEE Spectrum. Parviz and his team have been developing miniature circuits and simple LED displays and integrating these elements onto a contact lens-like polymer. They've tested them on rabbits who can wear the devices without harm. As Parviz points out, introducing Augmented Reality onto a contact lens is just a matter of time and effort.

Augmented Reality applications are starting to crop up everywhere, from table top games, to toy store displays. AR allows digital images and information to be blended with streaming video in real time. Using a computer screen or TV, the digital world and the real world overlap before your eyes. Pavik wants that statement to be literal: the overlap should be right before your eyes. As electronic elements become smaller and able to function at ultralow power, there should be little reason why electronics can't function directly on your body. AR contact lenses could also record information too. Biosensors on your eye would be able to monitor your health and then display that data to you through the AR interface. These devices would not only grant you increased knowledge, they could lead to bionic eyesight. High powered cameras could beam their recorded images directly onto your eyes through the lens, letting you see further, sharper, better.

Well what do we have here?

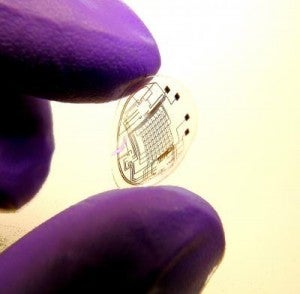

To date, Parviz's team has made some great first steps into proving that the AR contact lens concept is possible. Here's a quick summary of the accomplishments they list in the IEEE article:

- Parviz has developed several micro circuit components suitable for use on a contact lens. These include: control circuits, power circuits, communications circuits, an antenna, and a LED. That LED was activated to provide a single pixel in the field of vision.

- All of these elements consisted of semitransparent hardware that was embedded onto a polymer or glass that emulated a traditional contact. The AR contact prototype was then embedded in a biocompatible polymer to keep toxins inherent in semiconductor materials from spreading onto the eye.

- The entire structure was tested on a rabbit eye for 20 minutes without ill effect and the LED was lit.

- The team has also developed a simple biosensor that could be used to determine blood glucose levels by monitoring the eye's surface.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Yet these are just the first steps to actually creating an AR contact lens. That single LED is just one pixel, ideally you would want many more. According to Parviz, the useful image area of a device directly on your eye is about 1.2 mm. The current LED setup is about 300 microns which creates a single pixel that is a donut 112 microns in diameter and 60 microns thick. The goal is to create an array of 3600 pixels each 10 microns in diameter and 10 microns apart.

Once you generate an LED screen, you still have to get your eye to focus on it. Parviz reccommends the use of several thin micro-lenses that would fit with the AR contact. Essentially you would have just a few more layers of polymer that act as a telescope to get the LED image correctly seated on your retina.

Powering a contact is going to be interesting. Obviously a wireless system would be best. The University of Washington team created an RF circuit that could pick up energy broadcast from a battery pack in the 900 MHz to 6 GHz bandwidth - ideal for not frying your body with power. Parviz also suggests that a miniature solar cell could provide energy for the contact. Either way, the amounts of power supplied would be small (100 microwatts through RF, maybe 30 microwatts from the solar cell). The good news is that very little power is really needed. A LED situated directly on your eye shouldn't be very bright in order to be work. In fact, we could see a passive display (light is blocked instead of generated) work just as well as an active one. A passive system would work much like an LCD screen, where the ambient light of what you were looking at would function as a backlight.

What I find exciting about Parviz's work, and his ideas for the future, is that the AR contact is an ideal level of technology for many users. While we could one day have images broadcast into our brains, or enhance our eyes through genetic engineering, I find those concepts a little alien and uncomfortable. What happens if someone hacks your brain feed, or if there's a problem with the genetic manipulation? AR contact lenses could provide bionic eyesight, an integration of digital and real world images, and health monitoring as effectively as these other hypothetical systems. And if anything goes wrong, or if you want to upgrade to the newest technology, well, you just take the contact off and replace it.

As Parviz points out, his team still has many hurdles to overcome. They've tested circuit elements, but they haven't actually created the integrated chip they would need for AR. They've lit a single LED, but they haven't actually generated an image. There are many more parts of the puzzle that have to be created and then miniaturized to fit in the tiny space allotted. It will likely take years if not decades for these engineering problems to be solved. Still, I have high hopes for the technology. Parviz has a healthy National Science Foundation grant and I think the demand for the kind of device he describes is great enough to encourage others to enter into the field as well. Like the 100 million other contact wearers out there, I put plastic on my eyes every morning to improve my vision. Someday, with the help of AR technology, I hope to improve it even further.

[photo credits: Parviz Research Group, University of Washington]

Related Articles

Scientists Send Secure Quantum Keys Over 62 Miles of Fiber—Without Trusted Devices

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading