Gene Therapy Turns Several Leukemia Patients Cancer Free. Will It Work for Other Cancers, Too?

A new cancer treatment called targeted cellular therapy has generated a lot of excitement in the field. Researchers tried the approach on patients suffering from lymphocytic leukemia with no other treatment options. After receiving targeted cellular therapy, 26 of 59 patients, including 19 children, are now cancer-free.

Share

A new cancer treatment pioneered at the University of Pennsylvania has generated a lot of excitement in the field in addition to a handful of breathless media reports. Called targeted cellular therapy, the approach has given several dozen patients what Laurence Cooper of the MD Anderson Cancer Center called “a Lazarus moment.”

The patients all suffered from lymphocytic leukemia and had exhausted other treatment options. The researchers, Carl June and David Porter, announced the results recently at the American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition in New Orleans.

“Those patients were facing certain death,” said Cooper, who wasn’t involved in the Penn study but is researching a similar treatment at MD Anderson.

After receiving targeted cellular therapy, 26 of 59 patients, including 19 children, are now cancer-free. Patients with the acute form of the cancer, which affects both children and adults, were especially likely to respond positively to treatment.

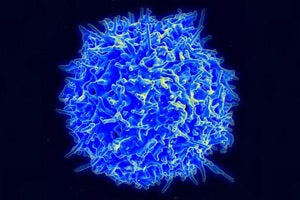

Targeted cellular therapy is an extension of long-standing efforts to ramp up the patient’s own immune system to destroy cancer cells. With advances in genetics, doctors can now reconfigure patients’ T cells to target a particular type of cancer cell.

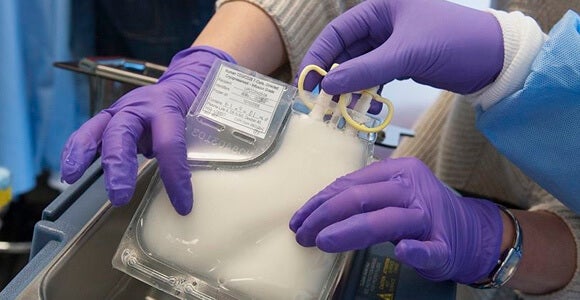

June and Porter removed the patients' T cells and genetically “rebuilt” and multiplied them before reintroducing them into the patient's bloodstream. The weaponized T cells find and destroy all cells with the protein CD19 on their surface, which includes the cancerous B cells found in chronic and acute lymphocytic leukemia.

Patient Doug Olson had long suffered from chronic lymphocytic leukemia, or CLL, when in 2010 he became one of the first patients to undergo targeted cellular therapy. A few weeks after his treatment, June and Porter could find no cancer cells in Olson’s body.

“The immune system eradicated his tumor. He had pounds — literally pounds — of tumor, and it went away in less than a week. It was an astonishing event that we saw,” June said in a Penn video.

More than 3 years later, Olson still shows no signs of CLL. Other early patients have also remained in remission, according to the doctors.

“There are clues that the T cells continue to kill leukemia cells in the body for months after treatment. Even in patients who had only a partial response, we often found that all cancer cells disappeared from their blood and bone marrow, and their lymph nodes continued to shrink over time. In some cases, we have seen partial responses convert to complete remissions over several months,” Porter said in a news release.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The treatment isn’t without risk, though. Patients suffer severe flu-like symptoms while the revved-up immune cells do their work. They require round-the-clock medical care, sometimes including the immunosuppressant drug tocilizumab. None have died from the treatment.

The modified T cells, which remain in the body, also destroy patients’ healthy B cells, which also express the CD19 protein. B cells help the immune system fight infection by making antibodies, and patients may require gamma globulin treatments as a preventive measure.

Of course, bone marrow transplants, a long-standing therapy for leukemia which also works by supplying patients with higher-functioning T cells, carries quite serious risks. One in five patients who undergoes it dies, and many aren’t able to have the surgery because there is no suitable donor available.

Will arming T cells lead to treatments that bring those suffering from other types of cancer back from death’s door? It’s a matter of finding other molecules like CD19 to target on the cancer cells without killing too off cells that patients can’t do without, Cooper explained.

CD19 lends itself to potential treatments for various types of leukemia and lymphoma. Cooper is part of a team researching a treatment for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that targets CD19.

“We don’t have a really long list of other molecules,” he said.

But they do have a few leads. Researchers are pursuing similar approaches for pancreatic and breast cancers as well as glioma, the type of brain cancer that killed Ted Kennedy.

“It’s a ‘you have a hammer, go get some more nails’ type thing,” said Cooper.

Images: Genetically engineered T cells, Porter, June and colleagues courtesy University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine; T cell, NIAID via Wikimedia Commons

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading