First Balloons and Drones, Now Dirigibles: The Race for a Truly ‘World Wide’ Web

Share

Facebook wants to be as cool as Google. Google wants to be the most innovative tech firm in history. Both are aiming to deliver internet access to the world’s offline billions—one with balloons, the other with drones. But what about dirigibles?

Dirigibles (or airships) figure prominently in early 20th century propaganda, the adventures of Indiana Jones, and alternate universes (see the TV show Fringe). But excepting eye-in-the-sky ads at sporting events, the dirigible is largely out of fashion.

Space firm, Thales, thinks that needs to change.

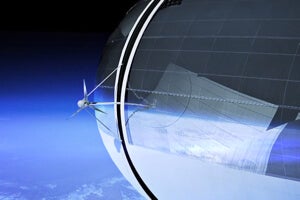

The maker of commercial satellites knows well the cost of putting hardware into orbit. So what about something a little lower and cheaper? Enter StratoBus, an autonomous dirigible designed to lug 200 kilogram payloads into the stratosphere.

At 20 kilometers, StratoBus would operate above commercial airliners and below space divers (see Felix Baumgartner). Sunlight would bathe the 70- to 100-meter dirigible’s solar panels all day, while its energy storage system would get it through the night—powering its instruments and twin propellers.

Unlike Google Loon, StratoBus would be a stationary system. Its carbon fiber shell would be designed to minimize wind resistance, while its props dynamically counteract winds reaching up to 90 kilometers an hour.

The 200 kilogram payload (equivalent to a small satellite) could be used for Earth observation missions including border surveillance, oil spill detection, coastal erosion studies—even, Thales suggests, monitoring pirate ships.

And of course, StratoBus could also provide a lower-cost alternative to launching telecommunications satellites or building expensive ground infrastructure. The airships could provide mobile internet and GPS to remote areas, boost signal in crowded areas, or act as a complement and go-between for telecom satellites.

We like the idea. Google’s passive balloons may need to be carefully coordinated to prevent holes in the network, while Facebook’s drones may face payload constraints.

Thales estimates StratoBus could operate autonomously for up to a year and have a five-year lifespan overall. But the firm doesn’t anticipate having a prototype up and running for another five years.

Likely, this early in the game, cost isn’t remotely calculable. Will a dirigible with a five-year lifespan be cheaper than a satellite with an average 10- to 15-year lifespan? Would customers need to trash their StratoBus after five years and buy a new one? Or might it be refitted for less?

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Facebook is likewise still in the early stages of their solar drone proposal. The firm recently seeded a lab with some fifty aerospace experts and bought the maker of the Zephyr solar drone, Ascenta. The idea isn’t as far fetched as it might seem.

Last year, we wrote about Solar Impulse, a solar plane that crossed the US in installments and holds world records for the highest (30,300 ft), longest (26 hours), and farthest (693 miles) solar powered flights.

Given Solar Impulse’s sluggish pace and dubious scaling potential, we suggested that although such technology may never make it into commercial flight, it could well compete with Google Loon for non-satellite telecommunications networks. (Maybe we’ve got a fan over at Facebook—or maybe it’s just an obvious idea.)

Google Loon, meanwhile, is an attractive proposal for its simplicity. The balloons would join StratoBus in the stratosphere, but instead of powering props to fight the wind—Loon balloons go with the flow. A network of such balloons would encircle the Earth providing internet access to remote areas.

Google is also the furthest along of all three projects. One of their balloons recently clocked its first around-the-world trip in just 22 days. Though it was a quick circuit, it also highlighted a few challenges in riding the winds. Seasonal wind patterns, for example, can be hard to predict, and their balloon did a "few loop-de-loops" over the Pacific.

But the team is honing their wind prediction models and say they can now more efficiently control the balloons' altitude. This allows them to catch favorable winds to maintain course. (They used such methods to dodge the polar vortex.)

Whether balloons, dirigibles, or drones, there's a race on to connect the globe. Added to lower launch costs, such inventions may finally realize the "world wide" part of the web.

Image Credit: Thales, Solar Impulse/YouTube, Google

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading