Cure For Multiple Sclerosis? Liberation Procedure Moves Forward

Share

For years, scientists have struggled to understand why the immune systems of multiple sclerosis patients attack their own bodies. With such a debilitating disease, a simple cause – and a simple cure – might seem too good to be true. In the past we've been covering new developments in the work of Dr. Paolo Zamboni, which suggests that a commonplace surgery might be enough to halt damage to patients’ immune systems. The so-called “liberation procedure” is gaining steam, causing controversy, and (most recently) attracting funding to investigate what could be a major step towards curing MS.

For those who haven't read our previous two stories on the matter (here and here), Zamboni’s theory identifies poor blood drainage from the brain as the primary culprit in MS symptoms. The answer? An angioplasty, a simple surgery to improve the blood flow of narrow or obstructed vessels. Many MS sufferers have undergone the procedure with reported success, and many more are seeking it. Controversy surrounds Zamboni’s underlying theory, the inconsistency of results, and whether hospitals should offer the unproven technique.

Last month, the National MS Society and MS Society of Canada devoted $2.4 million to fund research into the liberation procedure. The organizations announced that the money will be divided into seven research grants intended for research that explores the link between MS and what Zamboni considers its cause: “chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency,” or CCSVI. Research teams include a combination of experts in both MS and vascular tissues, working in tandem to investigate CCSVI and its role in the disease. To many, the awarding of this money - a decision made by many experts in the field - vindicates Zamboni's theory, which has been the subject of considerable controversy since its publication last year.

A few additional updates: Since our last article, additional studies have supported the link between CCSVI and MS. Simka et al. published an article in April in the journal International Angiology, and found that 90% of MS patients also have some form of CCSVI. An Australian youtube user named kezzcass has been documenting her own amazing success following surgery on a youtube channel. Finally, there's a web forum on CCSVI that was hosted by the American Academy of Neurology and the MS Society. It includes discussion by Zamboni, Zivadinov, and Dr. Aaron Miller of the National MS Society. The video can be seen at the end of this story.

Background

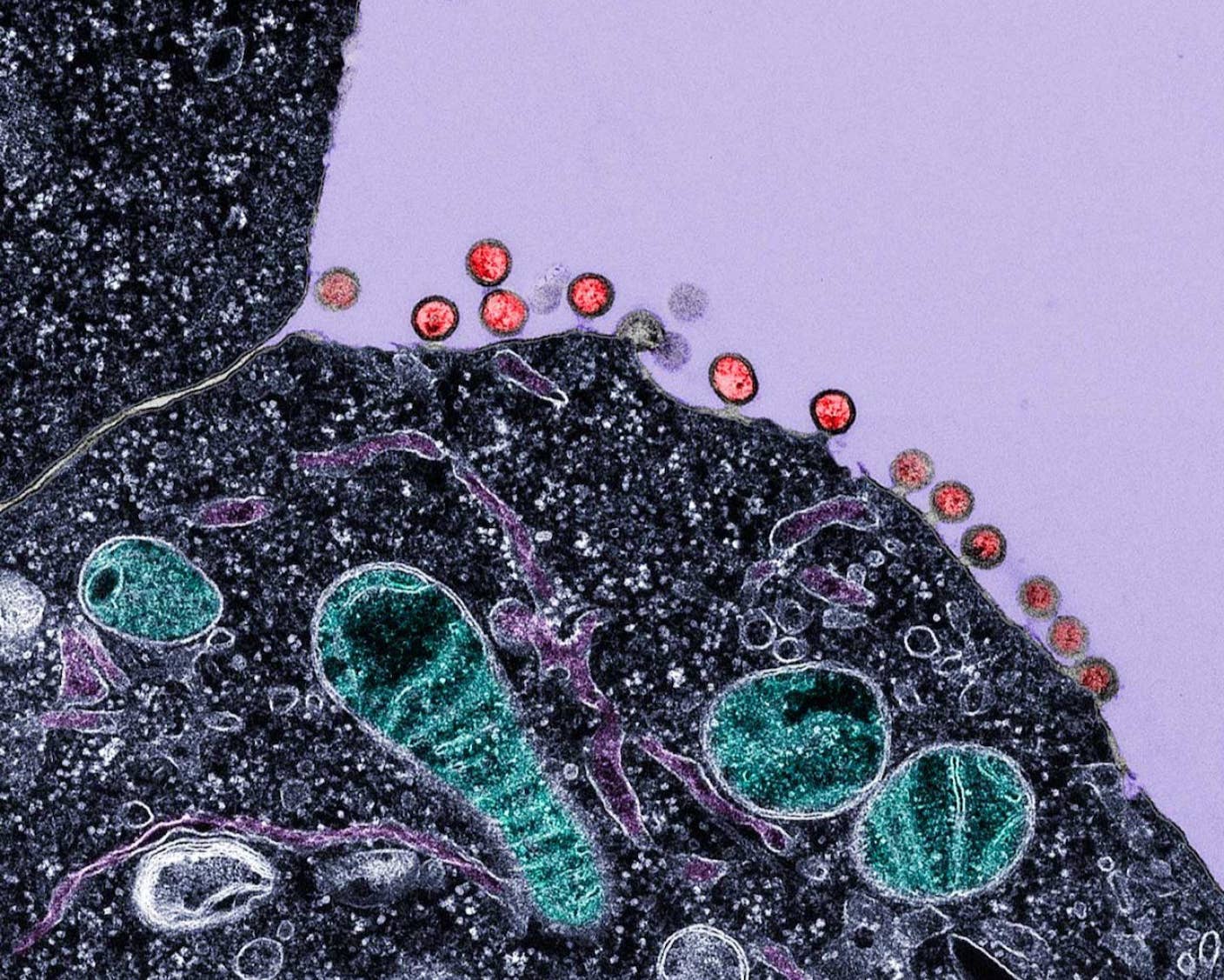

Multiple sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that affects over 2.1 million people across the world. Usually beginning in adulthood, immune cells begin to attack the body’s myelin, a fatty material that surrounds the axons of neurons in the brain. Myelin helps neurons to carry electrical signals through the nervous system; as myelin is destroyed in MS patients, a wide variety of physical and cognitive deficiencies begin to emerge. The symptoms vary depending on where in the brain the myelin damage occurs, but common problems include fatigue, loss of coordination, bowel and bladder disfunction, dizziness, and a range of cognitive and emotional changes.

There is no cure for MS, so most current treatments aim to mitigate the symptoms of the disease and modify its course over the lifetime. A variety of drugs are available that suppress the immune system and slow the process of demyelination – but many of the drugs require weekly injections, and carry difficult side-effects. Despite the relative success of treating MS symptoms with drugs, we still don’t understand why the immune system attacks the body’s own myelin – but Dr. Zamboni has a theory.

The Theory

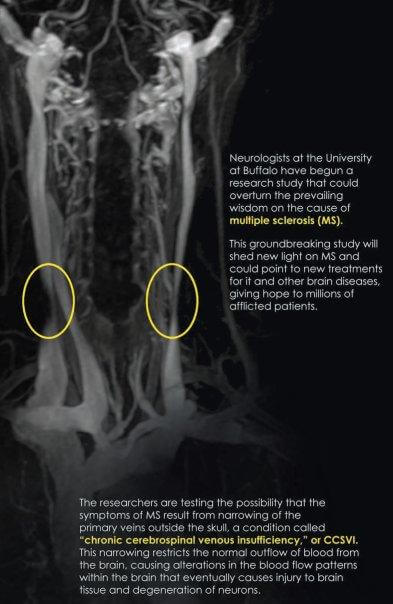

Zamboni – whose own wife has MS – recognized that in many patients, the three veins responsible for draining blood from the brain (the two jugulars and the azygos) are tangled or constricted. He named this symptom “chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency,” or CCSVI. In a healthy adult, blood vessels in the brain are impermeable to many of the blood’s contents – the blood brain barrier protects the brain from potential harm (e.g. bacterial cells) and only gives passage to smaller molecules like oxygen, carbon dioxide, hormones, and so on. Zamboni hypothesizes that poor drainage caused by CCSVI might cause a reflux of blood into the brain that increases blood pressure. The results of this pressure are twofold. First, iron is deposited out of the blood and into the brain. Second, if blood vessels are stretched out, they can tear microscopically and leak immune cells into the brain. The immune system then attacks the iron deposits, and MS results.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This is where the liberation procedure comes in. Zamboni proposed that balloon angioplasty, a common technique for widening blood vessels, should alleviate the symptoms of MS. Last year, he published a study of 65 MS patients who underwent the surgery; two years after the procedure, 73% of the subjects had no symptoms. Since his research was initially reported, many MS patients throughout the world have sought the liberation treatment from angioplasty surgeons.

But not everyone is convinced. Controversy has surrounded Zamboni's highly publicized work since his initial study was released. The link between poor drainage and MS is far from perfect, as a collaborative study between Zamboni and Dr. Robert Zivadinov revealed: only 60% of MS patients showed CCSVI, compared with 43% of patients with different neurological disorders and 22% of healthy subjects. Many patients' angioplasties had only short term success, with 47% of patients' veins narrowing again within a year of surgery. Other experts of MS remain skeptical of Zamboni's claims until more conclusive evidence supports his theory - something the new research grants will hopefully provide.

Legal concerns have also slowed the number of liberation procedures, as hospitals safeguard themselves against an unproven technique. Many hospitals' lawyers have stopped the procedures until it has been proven within peer-reviewed processes, which has kept many hopeful MS patients from receiving the treatment. As with stem cells and other controversial procedures, this has led to an increase in medical tourism to countries outside the US.

The $2.4 million in research grants is promising - it shows that Zamboni's theory is taken seriously enough to warrant further research. The concerns regarding his theory are very real, and should be addressed before the liberation procedure is regarded as some miracle cure. Hopefully new research will vindicate his approach; even if it doesn't, probing his findings should help to clarify the origins of MS immune response, which is a step in the right direction.

[image credits: Alessandro Vincenzi, The Globe and Mail; The Multiple Sclerosis Resource Center; Bret Gundlock, National Post]

Drew Halley is a graduate student researcher in Anthropology and is part of the Social Science Matrix at UC Berkeley. He is a PhD candidate in biological anthropology at UC Berkeley studying the evolution of primate brain development. His undergraduate research looked at the genetics of neurotransmission, human sexuality, and flotation tank sensory deprivation at Penn State University. He also enjoys brewing beer, photography, public science education, and dungeness crab. Drew was recommended for the Science Envoy program by UC Berkeley anthropologist/neuroscientist Terrence Deacon.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading