Catching Students (and Teachers) Who Cheat In the 21st Century

Share

Your child's smart phone could be helping them fake their own intelligence. School administrators, teachers, and industry organizations are worried that high tech gadgets are making it easier than ever before for students to cheat on exams - and they're doing something about it. Companies like Caveon in Utah have adapted forms of statistical analysis to determine which students are cheating based solely on their test results. Bring whatever kind of devices into the testing room that you like, the evidence of cheating will be in your answers. According to the New York Times, the Department of Education in Mississippi claims that they've reduced cheating by 70% since hiring Caveon back in 2006. Many more states are clients of the company, alongside The College Board, and IBM. Yet their kind of data forensics is only one of many ways in which we could reduce academic dishonesty. For every technology that enables cheating, there will be another that catches those that use it.

Standardized Cheating

What exactly are companies like Caveon doing when they perform data forensics? Well, simply put, they are looking for things that don't make sense. Did your answers seem to agree too closely with others who took the test? Have your grades increased dramatically over a previous exam? When you erased, did you always end up changing to the correct answer? By looking for statistically unlikely events, analysts can identify students who cheated. It doesn't matter if you wrote things on your hand, whispered to a neighbor, or texted a friend for answers - in the end your cheating will show up as a statistical anomaly that Caveon can find. Small fluctuations, as you would expect from a student test to test, or small correlations (every student got question 20 right because it was so easy) won't trigger the alarms. It's only when you hit a one in a million chance that a result could happen randomly that Caveon's ears start to perk up.

Many of these techniques are adaptations of standard analytical methods used in forensic accounting, and other fields of fraud detection. There are naturally occurring statistical patterns in most things that humans produce. For example, Benford's Law tells us that humans use more numbers starting with 1 or 2 than we do 8 or 9. (Strange but true. There's a really fun discussion on this counter-intuitive statistical fact on NPR's Radio Lab.) Unless a test taker is aware of these natural laws and able to mimic them, their cheating answers will show up as observable anomalies. If they mask their behavior...well, they probably aren't improving their scores by much at all (and they've shown themselves to be pretty intelligent, too.)

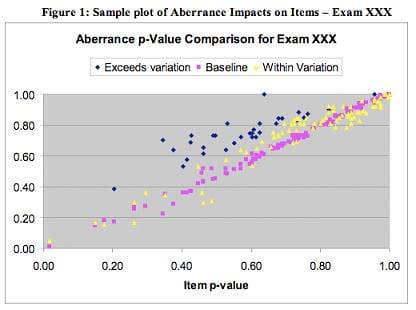

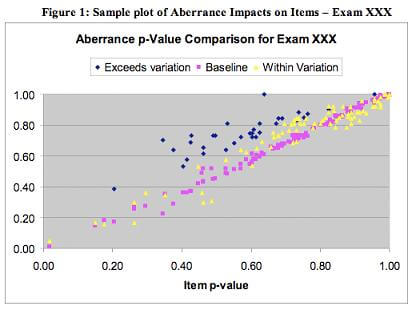

Pink marks show baseline values, yellow the answers that deviate slightly. Blue markers are so deviant they may indicate cheating. Graphs like this help Caveon find the academically dishonest.

As you can imagine, data forensics is easiest to explain in terms of standardized tests where students fill in ABCDE answers to multiple choice questions. The rise of standardized tests in the US, especially as a result from the No Child Left Behind Act, has made such analysis an important tool in catching a large number of cheaters. Standardized tests are some of the most stressful (and arguably impactful) exams a student will take, and the pressure to cheat may be greatest here. Students, of course, aren't the only ones who feel the pressure to cheat.

Teachers do, too. Popular books like Freakonomics have highlighted the ways in which teachers may alter student's tests to improve their own assessment ratings. Or because they want their students to get better funding. Similarly, many industrial/professional groups like the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying, or the Association of Government Accountants (both Caveon clients) recognize that their members will feel pressure to cheat on their tests, or alter the test scores of their friends or employees. In all of these cases, forensic analysis of test results can help identify who is sharing answers, or otherwise cheating on the exam.

As analytical programs become more sophisticated, and more widely used in schools, we'll be better able to catch people who cheat on standardized tests. In fact, I'm willing to bet that, if properly applied, the kind of techniques used by Caveon could dramatically curtail cheating in the years ahead. Data forensics could be the means to make cheating on these exams so difficult to get away with that fewer and fewer students will try. The future of standardized tests could be relatively cheat-free. Yet there are other areas of academic dishonesty in which data analysis alone can't always help.

Plagiarism

Outside of standardized tests, plagiarism is perhaps the most infamous form of cheating. It's a growing concern in a world where any student can go online and find hundreds, if not thousands, of papers that have been written on any subject. There are many internet-based services that allow you to scan an electronic document and detect how much, if any, has been copied and pasted from online sources. With enough processing power you can quickly compare one document to millions of others. There are some services that are sophisticated enough to detect when a student's essay matches the same general flow as a previously written essay (a possible sign of plagiarism). Yet the boundaries between referencing and interpreting someone else's work and outright plagiarizing it can be blurry in some instances. Testing for plagiarism in a written paper is always going to be a bit subjective.

Less so, perhaps, for computer science. With methods similar to those used to detect plagiarism in writing, teachers are able to determine when a student is stealing someone else's code instead of inventing their own. Such anti-cheating measures have become easy to apply in academia, and the results have been enlightening. According to PC World, 23% of all cases of academic dishonesty at Stanford University have come from computer science students - well out of proportion considering they make up only 6.5% of the total. University of Washington professors estimate that 1-2% of all entry-level computer science work at their school is academically dishonest (either through plagiarism or students unethically collaborating on projects).

Are computer science students out there less honest than their peers? Probably not, but their choice of careers makes it harder for them to cheat without getting caught. Their instructors are good at developing algorithms to identify those who share or copy code, and their work is submitted in a format that is designed to be easily analyzed electronically. The real problem isn't that computer science students have such high rates of cheating, it's that we haven't been able to detect that same amount of cheating that is occurring in other disciplines.

One way to counter plagiarism is to decrease its usefulness to students. According to PC World, Georgia Tech allows computer science students to work with their peers freely, but requires them to list collaborators and orally explain the code they submit to an instructor. You can't just turn in a program, you have to understand it. That's a similar sentiment to many oral exams and thesis defenses you see in graduate school. Increasing the importance of oral evaluations in college could help curb cheating - at least until we develop sub-dermal speakers.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Is That Really Cheating?

In the battle between cheaters and cheater-hunters sometimes it's hard to say who is on the right side of the ethical debate. Many standardized exams have practice tests you can take to help prepare you for the real thing. Such practice isn't considered cheating. Unless, of course, the practice test comes from the wrong source. "Brain dumps" are online forums where students list the questions they just took on an exam, ostensibly so that future takers will know what to expect. Because such listings are generated from memory, they are generally inaccurate in one way or another, perhaps as different from the real exam as the approved practice tests. Yet studying one is considered cheating, while the other is not.

Sometimes even taking an approved practice test can be considered cheating. Recently a professor at the University of Central Florida told his class of 600 students that he suspected 200 had cheated on a midterm exam. The students turned themselves in after an offer of amnesty (dependent on their enrollment in an ethics class). The news made global headlines. What form did the students' malfeasance take? They studied a list of questions made by a textbook publisher. The professor copied many of these questions into his exam instead of generating his own. His plagiarism wasn't considered cheating, their studying of a public resource was. Interesting, no? Techdirt has more on this story, here, and you can see some fun college TV journalism in the following video:

As we move firmly into the information age, these sort of gray areas and double standards are going to crop up more and more. We're going to be able to find answers to almost any question online. Even if teachers generate their own completely new exams, there's only so many ways to test the same skill. Chances are that you could study for a test with questions that are remarkably similar to what many professors would ask you. Is that really cheating?

The better question is, why do we really care? In high school, it was a big deal if you worked with someone else on homework or a project. In college, many professors accounted for collaboration, and even allowed open book exams. In the laboratory at grad school if you weren't constantly collaborating and looking things up then you were probably making a mistake (actually, you were probably making a mistake no matter what you were doing...that's science for you). The truth is that the same skills that help a student cheat - communicating with others, knowing how to easily access reference materials, etc - are the ones we want them to have when they enter the workplace. Clearly each student needs to demonstrate that they have mastery of a subject, but why does that demonstration need to preclude the skills that could help them succeed later in life?

As we continue down our path of advancing technology, the rules of cheating in academia may need to be revised. If we continue to test for rote knowledge and basic calculation then we are setting the standard of education at a level that will allow our children to be easily replaced by computers and robots. Even synthesizing new material from reference sources (the backbone of most collegiate research papers) is a feat able to be performed by software available today. Evaluation of knowledge, rapid decision making - these are some of the skills at which humans excel over computers, and which students will need in the future.

Of course students will always need some rote knowledge, and a lot of basic level processing skills. Testing those skills will inevitably lead to tests that students can easily cheat upon, and so we will always need anti-cheating techniques like the ones Caveon sells. My point is this: Although advancing technology will help us catch cheaters even as it helps them get better at cheating, that cycle should really be avoided entirely. Test the skills that make humans unique whenever possible, and help students learn how to educate themselves with the resources around them. In the end we'll all have smart phones, virtual assistants, and (possibly) enhanced brains. The people who can take advantage of those technologies are going to excel. Even if you call them cheaters.

[image credit:Francis Storr, Caveon]

[source: New York Times, Caveon, PC World]

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

Scientists Want to Give ChatGPT an Inner Monologue to Improve Its ‘Thinking’

What we’re reading