CDC Issues New Guidelines for Tuberculosis As Drug-Resistant Forms Spread

Share

The 500,000 year-old pathogen responsible for tuberculosis (TB) has infected 1 out of every 3 people on the planet, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

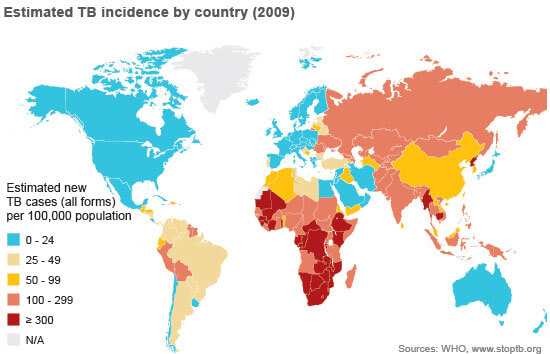

Though other worldwide infectious diseases, such as HIV, influenza, malaria, and hepatitis, often steal the limelight, the bacterium responsible for TB, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is incredibly prevalent, and could prove to be a much greater threat. Modern diagnostics and pharmaceuticals provide healthcare professionals with weapons to identify and wage pharmaceutical war against this disease, but WHO recently reported that drug-resistant forms of the bacteria are on the rise in eastern Europe and Central Asia, allowing evolved strains to kill 50% of those infected. In an effort to crack down on TB in the US, which has only about 4% of the population infected, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has issued new guidelines that provide a faster, more straightforward regimen that can reduce the time of treatment by two-thirds.

But can new plans lay the groundwork for eliminating TB in industrialized nations, and if so, can the same approach defeat TB across the world, even as new drug-resistant strains are gaining a foothold? As with any long-fought war, only time will tell.

People typically become exposed to TB when an infected individual expels the bacteria by sneezing, coughing or even talking. The bacteria then infiltrate through the respiratory passages and into the lungs. Because the bacteria grow slowly, multiplying 15- 20 times slower than typical bacteria, the immune system has a fighting chance to wall off the pathogens and keep them under control. Individuals with this "latent TB" are noninfectious, but if the bacteria are able to gain ground against the immune system — especially if it is suppressed by concurrent illness and/or poor health — the disease can progress to the "active TB" phase of disease. This usually occurs within 18 months of infection, although some individuals may carry latent TB in its dormant state around for many years before developing disease. Once active, the bacteria multiply, eventually destroying tissue and overwhelming the body's ability to repair itself to the extent that the lungs or other organs can be eaten away (which is why the old name for the disease was 'consumption').

Only those with active TB spread the bacteria to others. Individuals with weak or compromised immune systems, such as infants, the elderly, or immunocompromized individuals, are at particularly high risk for infection and subsequent disease progression. Statistically, 5 to 10% of infected individuals develop active TB over the course of their lives, accounting for the 9.4 million new cases of active TB and 1.7 million deaths in 2009 worldwide, with most of these infections in developing countries.

If you've seen any number of thriller/horror movies involving a pathogenic outbreak (a number of zombie movies come to mind), this sounds like a recipe for a pandemic. So why hasn't the human race been wiped out by TB already? Well, it almost did. In the 18th and 19th centuries, TB was common and close to being epidemic in countries that were experiencing overcrowding due to urbanization and industrialization, such as in Europe where the TB death rate was over 30%. Then medical practices and general hygiene slowly improved in the 20th century, which helped lower its threat, as well as the isolation of individuals with TB in sanatoriums. But it was the advent of the antibiotic streptomycin in 1948 which began to turn the tide. Today, TB treatment regimens employing a handful of the 10 FDA-approved drugs are utilized to treat both latent and active forms over the course of 9 months.

Herein lies the problem. TB treatment course is long, and even though patients are urged to complete the full drug schedule, they don't always do it. If people with strep throat struggle to take all the antibiotics, which is generally only 10 days, you can see how challenging it could be to take a pill a day for 9 months. When all the drugs aren't taken, then only the weakest of the bacteria are wiped out, so the ones that are the most resilient to the antibiotic survive. This is known as antimicrobial resistance (as we covered back in April) and is well described in the following video:

Even Sir Alexander Fleming, who made the serendipitous discovery of penicillin in 1928, warned the world about drug-resistant bacteria in his 1945 Nobel Prize address saying, “The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug make them resistant.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

As you might have guessed, people infected with TB haven't always taken all their drugs, which is why WHO issued warnings and established a new action plan in light of new strains of drug-resistant TB arising in Europe. In fact, 440,000 new patients with drug-resistant TB are identified globally every year. These new strains of TB are unfortunately a human-made problem. Patients infected with the new resistant strains may need treatment for up to two years and require surgery to remove infected tissues. So monitoring disease progression is not only important for patients, but for the population as well. Imagine if patients with the drug-resistant forms don't take all their medication. They would effectively be helping to create the next superbacteria, which could lead to epidemic infections across the world.

It's clear that identifying individuals who have latent TB is a top priority in order to start them on treatment before they become infectious. This is the aim of the new CDC guidelines released in early December. Even though TB is not widespread in the US, it is still a concern because of its latency and the aging population. The new recommendations reduce treatment time to 12 weeks and replaced the 270-daily doses of the old schedule with 12 once-weekly doses. The CDC report emphasizes the need for close monitoring to minimize adverse reactions as well as ensure that the full drug regimen is taken.

There has been a lot of doomsday forecasting about the potential for a global pandemic, whether it is bird flu or something as equally virulent, but the truth is that the new drug-resistant TB strains pose as much of a threat to the world today as they did a few hundred years ago. Early detection of latent TB would be ideal to shutting down the bacteria, and thereby stopping its spread, but diagnostics tests still struggle to be accurate. Fortunately, developments are underway that may lead to turning the tide against TB, including a vaccine for latent TB in clinical trials. But for now, the efforts by WHO and the new policies of the CDC are strides in going on the offense against one of the humankind's oldest enemies.

To learn more about the worldwide movement to combat TB, check out the Stop TB Partnership.

[Sources: CDC, Merck Manual, nobleprize.org, reuters, WHO]

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Thousands of Everyday Drone Pilots Are Making a Google Street View From Above

What we’re reading