The Era of Robotic Warfare Has Arrived – 30% of All US Military Aircraft are Drones

Share

Some herald it as the cure for terrorism, others deride it as mindless video game warfare, but few doubt that the American era of drone warfare has arrived. From short range surveillance craft like the Raven to missile packing hunter-killers like the infamous Predator, the US military is awash with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). According to a recent report from the Congressional Research Service, nearly one in three US warplanes are drones...and those machines are changing the way the world wages war. US soldiers in Afghanistan rely more and more upon intelligence gathered from drones, and President Obama recently lauded the precision and success of deadly drone-strikes against top terrorist targets in Pakistan. Meanwhile all advanced militaries in the world, from Israel to Russia, seem to be improving their own drone capabilities. Yet with this surge in robotic craft come rising concerns over the ethics, and liabilities, of UAVs. The rise of drones seems unstoppable, but will this shift in tactics improve or deepen the ravages of war?

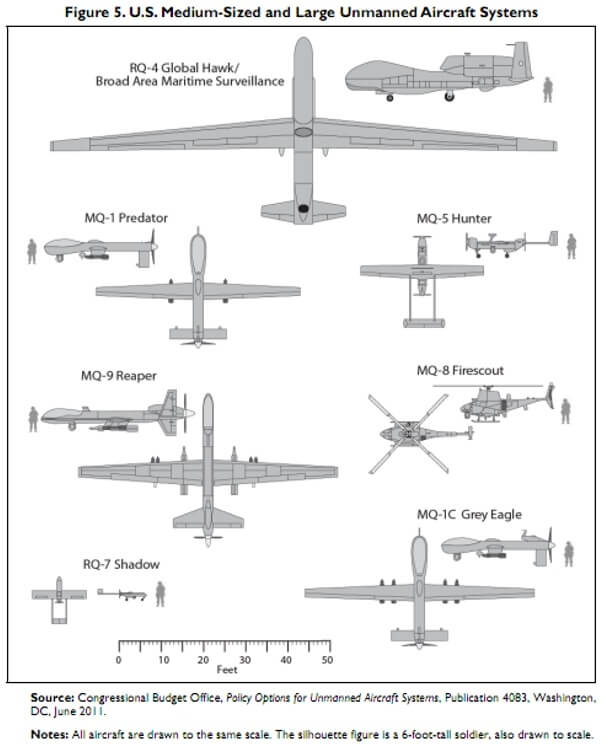

Wired's Danger Room broke the Congressional Report Service story earlier this month, calling out some of the most enlightening figures from the 50 pages study (mirrored here). About 31% of US aircraft are unmanned. That represents an amazing change over the past few years as such UAVs only represented 5% of the US total in 2005. Of course, the vast majority of these drone craft are relatively small, able to be launched by hand. The most prolific is the Army's Raven, with 2200 on order and 1300 delivered. The most widely discussed, and feared, drones are the Predators and Reapers, which can carry heavy ordnance (including Hellfire missiles) and are often operated remotely by human pilots stationed in the US. However, CRS reports that there are only about 160 Predator and Reapers in service.

Why is the population of drones rising exponentially in the US military? Again, the CRS numbers are very revealing. While representing more than 30% of the total aircraft flown, drones account for just 8% of the warplane budget. Nearly forty Predator and Reaper drones have crashed in Afghanistan and Iraq (with the loss of small UAVs like the Raven being considerably higher), yet the accident rate for Predators has dropped significantly in the past few years falling from 20 cases per 100,000 hours in 2005 to just 7.5/100k in 2009. That accident rate puts the Predator (and Reaper) on par with the F-16! And pilot lives are never lost in a drone crash. On a case by case basis, individual UAVs may or may not be more cost effective than manned planes for a particular mission, but as a whole they seem to be a better investment. In fact, the US is on track to spend $26 billion on drone R&D between 2001 and 2013. A small fraction of the total US military budget, but possibly the investment that may yield the highest dividends.

No new technology can be borne into battle, however, without carrying with it some new dangers as well. Critics of the reliance on drones point to two large security risks, both in the handling of data. First, most aerial drones are not used directly as weapons, but as mobile platforms for intelligence gathering. Even the Predator comes packed with cameras to observe its surroundings in high definition and at high speeds. With the surge in the use of UAVs has come a tidal wave of video and sensor information, much of it streamed to remote locations far from the point of operation. There have already been a few well-reported cases of insurgents tapping into that data stream for use against US troops. Such risks are likely to increase as technology-use among opposition forces improves.

Second, whether a drone is operating under its own programming or being remotely piloted by a human, they are open to receive control commands. The possibility of drones being hacked is very real, and some claim that the recent capture of an RQ-170 spy drone in Iran was accomplished through such hijacking techniques. Whether or not that's the case, UAVs are clearly susceptible to inflight theft in ways that manned vehicles simply are not.

The following video describes the RQ-170 and its recent capture by Iran:

Above and beyond technological concerns is the growing opposition to UAVs on ethical grounds. The issues raised by opponents are varied but can be categorized into three general critiques: that drones give the US (and other governments) unchecked ability to assassinate their targets, that drones developed for use in foreign conflicts may eventually be used against a nation's own citizens, and that drones desensitize soldiers to killing (and that, by extension, a large number of civilians have been killed in drone strikes). Among those raising concerns on the growing use of drones is the ACLU, which has filed suit to gain access to the US' so-called “targeted killing program” that seeks to eliminate high-value targets using Predators. Protestors in both the US and Russia have reported strange surveillance craft hovering during their demonstrations, reportedly the use of drones as domestic spies. Public opinion on drones in the UK, and much of the EU, is generally considered poor. While it is difficult to find a single source that articulates the wide range of outrage against drone warfare, the following news segment from Russia Today certainly tries:

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Trivializing the concerns over the use of UAVs in war would be a mistake. Yet the armed forces of nations all around the world seem undeterred by opposition voices. As mentioned in the CRS study, the per year investment in drone R&D is increasing, projected to rise to $3.9 billion from the US Department of Defense. Among the upcoming vehicles expected to see launch is the Avenger, the successor to the Predator and Reaper, capable of flying higher, longer, and 50% faster and carry upwards of 50% more/heavier ordinance. Private companies are developing scouting UAVs armed with anti-personnel weapons for use by border agents and police. The US Navy is developing both unmanned jet fighters and automated turrets capable of destroying drones. Trade organizations for UAVs are attempting to recast their public image in the EU, Israel has its own UAV projects, and systems from China and Russia can be assumed to be developing on pace as well.

Simply stated, no matter what moral issues are raised, UAVs are not going away. The tactical and economic advantages are too large for any military to sacrifice. Accordingly, governments are becoming more vocal in the support of this technology. President Obama recently admitted to use of Predator drone strikes in Pakistan, which were long rumored to be killing Al Qaeda operatives, during a recent Google Hangout. Obama, however, denied that such strikes had high rates of collateral damage and generally supported the use of drones as precise (see clip below, full video available here).

US allies are likewise vocal about their support. Yemen has requested, and received, increased US drone patrols as the nation prepares to shift power from its president to its vice-president. It's hoped that well-placed UAVs could curb the growing threat of terrorist groups hoping to influence the country during political volatile times. Even as Pakistan, and other nations have condemned US strikes as violations of the sovereignty of their air space they have requested access (sales) of the vehicles to their own militaries.

The fact that no armed force wants to sacrifice the use of drones should suggest the recent success and ongoing potential of this technology. Undoubtedly the growing reliance on UAVs has altered warfare and will continue to do so. With that change we should also expect battles over domestic use of these aircraft for it's almost certain that law enforcement agencies will find the vehicles just as advantageous as their military counterparts. We may also fear that remotely targeting enemies will lend a certain “numbness” to soldiers around the globe. Yet that fear was raised with long range high altitude bombers in the Second World War, with nuclear proliferation in the Cold War, and perhaps with every military technological innovation since. Smart warfare seeks to remove soldiers from danger even as it makes those soldiers more effective. UAVs are no exception. If we must argue against unmanned warfare, let us argue against warfare itself, for it is the intention of deadly force, not the technology that delivers it, which ultimately bears responsibility for the death and destruction that follows. If we must use robots to fight, let us use them well, use them decisively, and then stop and transform them into something more productive. Ultimately it is the peaceful applications of such drones: search and rescue, novel construction, exploration, etc, that will hopefully form their lasting legacy.

[image credits: Public Domain image (Brigadier Lance Mans, Deputy Director, NATO Special Operations Coordination Centre), Congressional Research Service]

[video credit: PressTVGlobalNews, Russia Today]

[source: Congressional Research Service, Danger Room, WhiteHouse.gov]

Related Articles

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

This Robotic Hand Detaches and Skitters About Like Thing From ‘The Addams Family’

Waymo Closes in on Uber and Lyft Prices, as More Riders Say They Trust Robotaxis

What we’re reading