Satellites Track Humans, Now It’s The Animals’ Turn

Share

Satellite technology is a modern-day "Wonder of the World." Consider that currently over 1,000 active satellites orbit the Earth, communicating with ground-based transmitters and receivers for a host of applications, such as delivering scientific measurements, weather information, and television programming, to name a few. Since the launch of Sputnik I in 1957, satellite technology has increasingly connected people together, whether in the same town or on opposite sides of the planet, effectively making the world flat.

One of the increasingly employed technologies is GPS tracking, which many of the world's 6.6 billion mobile subscribers (over 90 percent of the world's population) have come to rely on. For the last few decades, scientists too have utilized satellite tracking to monitor wildlife to better understand their migratory patterns and the impact humans have on their environments. Recently, for the first time, satellite tracking has provided insight into the last of the marine megavertebrate species to be monitored by satellite: the giant manta ray.

Although this latest study is a success story for a technology that has matured over two decades, it also highlights just how far behind satellite tracking of animals is compared to humans and how desperately that needs to be changed.

The research, published in PLoS ONE (read the full article for free here), described how six manta rays were tagged with trackers as they traversed nearly 700 miles around the Yucatan peninsula and were monitored for up to 64 days before the trackers fell off. The researchers discovered that the manta rays predominantly remained in warmer water (26-30°C) of less than 50 meters deep, but spent nearly 90 percent of their time outside of Marine Protected Areas where human contact is minimized.

Because manta rays are currently listed as 'vulnerable' to extinction by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, knowing the degree to which they intersect with human activities is essential to understanding their long term survival. This is especially important as the rays are often at risk of being hit by shipping boats, chopped up by fisherman for use as shark bait, and hunted for their cartilaginous gill rakers that are used in Eastern medicine practices.

Furthermore, manta rays are exposed to humans increasingly in the megafauna tourism industry that offers scuba divers a chance to swim with the rays. A study by The Manta Ray Of Hope Project estimated that a single manta ray brings in an income of $1 million to local ecotourism over its lifetime. The global tourism value of manta rays is estimated at $50 million a year, while the market value for the ray's gill rakers is $11 million, so the study concluded that there is much greater financial value to the tourism industry in keeping the manta rays alive. Unfortunately, though current population sizes are unknown, it is believed that giant manta ray numbers are dwindling rapidly.

Slate put together a video highlighting the study:

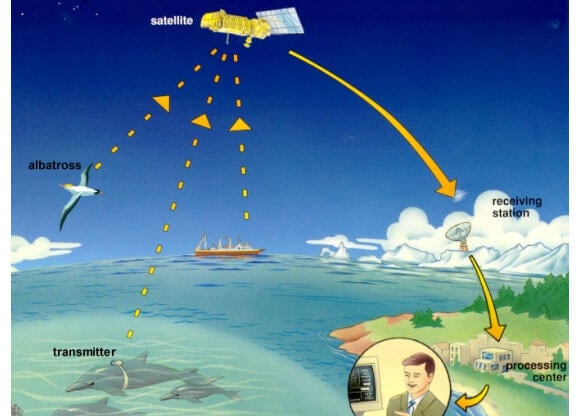

For over 30 years, the migratory patterns of marine animals, including sharks, turtles, and now giant manta rays, have been made possible by the Argos satellite system. Launched in 1978 as a joint venture between the French Space Agency, NASA, and the National Oceanic and Atmosphere Administration (NOAA), this system was originally intended for meteorological and oceanographic studies only. But in 1986, the system, which employs a number of satellites, was commercialized, allowing researchers to propose new uses for the system.

Since that time, satellite tracking via Argos has become a vital research tool for studying marine biology and ecology, with over 3,000 animals currently being tracked by Argos. A 2009 review in the journal Endangered Species Research found that satellite telemetry of marine megavertebrates was maturing into "an operational science." Tracking has helped researchers follow leatherback turtles making a 7,500-km journey across the South Atlantic, manatees trekking from Florida up to Rhode Island, and a host of sharks, which have seen an 80 percent population drop in the last 50 years. But the study also revealed a rather shocking truth: only 92 studies using satellite tracking were reported in the literature between 1987 and 2006 with less than a quarter of these studying marine mammals.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

In other words, we really have very little idea of what's going on under the sea.

As with other species that call the ocean home, it is difficult to gauge exactly what impact humans are having on marine life, but it doesn't look so good. We're doing a horrible job at managing the oceans between the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, whose size is exaggerated but still considerable, the loss of 10,000 shipping containers to the sea every year, and overfishing which has been projected to cause a global collapse of fish species by mid-century if action isn't taken. A recent study discovered that something as innocuous as replacing native trees along the coast of an atoll with non-native palms produced a cascade of effects resulting in a massive decline of seabird, plankton, and manta ray populations. It's also conjectured that humans cause extinction at a faster rate than new species can evolve, and though the rate of extinction may not be as rapid as some believe, increasing pressure on the ocean will only add to the 16 known marine species that have become extinct since 1972.

The ocean is considered by many to be the last great frontier on Earth, full of numerous resources and mysteries about life on Earth, so it is imperative that related technologies can be transferred rapidly to enhance marine studies. Recently, James Cameron made a well publicized dive in partnership with National Geographic to the Mariana Trench in a new submarine, beating Richard Branson to the punch and demonstrating how far submersible technology has come since the first dive in 1951 to the bottom of the ocean. Other projects are underway to use the power of modern technologies to explore the ocean, such as the development of underwater drones, which could turn out to be as successful as military drones have been.

New satellite tracking systems are also gaining momentum. An initiative called the International Cooperation for Animal Research Using Space (ICARUS) is focused on small animal tracking using radio transmitters (much smaller than the larger Argos tags) and hopes to be monitoring 1,000 small animals by 2014. Previous tracking of marine life using the 27 GPS satellites has been difficult because the tags are detectable only in shallower water and GPS can take at least a minute to coordinate a signal. However, newer Fastloc technology has reduced the amount of time considerably down to around a tenth of a second and extended the depth to 1,000 meters.

Still, if we will have smartphones soon that will be able to track our position down to the inch using a whole host of technologies, including wireless, GPS, and Bluetooth, to coordinate position, surely there must be a way to do something similar for wildlife monitoring. Satellite tracking has proven to be such a powerful technology that it's clear what's needed is an advanced telemetry and coordinated tracking system to monitor multiple species in real time.

And while it may seem like a tall order, such a system will be in place for humans in the near future, even in the face of international issues, legislation, and privacy concerns, so can't we find a way to monitor the rest of life on Earth as well?

[Media: NASA, National Geographic, WFU, YouTube]

[Sources: Argos, LA Times, PLoS One, Shark Savers]

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

Hackers Are Automating Cyberattacks With AI. Defenders Are Using It to Fight Back.

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through March 7)

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

What we’re reading