First HIV Prevention Drug Approved By The FDA

Share

Right on the heels of a new at-home HIV test receiving FDA approval comes word that the first HIV prevention pill has also been approved. Produced by Gilead Sciences, the dual-drug Truvada has been in use since 2004 as part of treatment for those infected by HIV. But studies in 2010 showed that the antiretroviral medication worked effectively to prevent contraction of the virus in at-risk individuals, such as those in relationships with HIV-positive partners or even sex workers.

Truvada is actually two drugs (emtricitabine and tenofovir) combined to make HIV replication in the body more difficult. Although it is used as therapy once the HIV virus has infected T-helper cells, its mechanism of action appears to work as well at stopping infection in the first place. When low dosages of Truvada are taken daily, the risk of infection was reduced by 42 percent in a trial of HIV-negative gay and bisexual men. Among heterosexual couples in which one partner was infected, the infection rate was reduced by 75 percent against placebo.

One member of the advisory panel who made the recommendation for Truvada's approval in May told the New York Times that the drug represented "an amazing opportunity to turn the tide on this epidemic." Every year, approximately 50,000 Americans are diagnosed with HIV.

But the drug is not a replacement for safe sex practices, such as the use of condoms, or a waiver from HIV testing. In fact, it is vital that anyone taking the drug for prevention purposes be HIV-negative. Why? To prevent the emergence of drug-resistant forms of HIV, which is why anyone taking the drug must be tested every 3 months. Resistance might also occur if people don't take the pills religiously, as low levels of the drug can strengthen viruses that can adapt to it, just as bacteria do with antibiotics.

A year supply of Truvada is estimated to be $13,000, and it's still unclear if insurance companies will cover any of the cost. They may very well want to wait until a recently announced clinical trial involving Truvada is completed before covering the cost. The 4-year clinical trial aims to test another HIV treatment, Selzentry, as an alternative to Truvada, which carries with it some concerns about bone and kidney damage.

Since the 1980s, governments and medical communities have had little more than cautionary education to prevent HIV from becoming a major threat to the human race. But Truvada's approval may open up a whole new approach to the prevention of HIV, signaling the beginning of the end for the virus.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

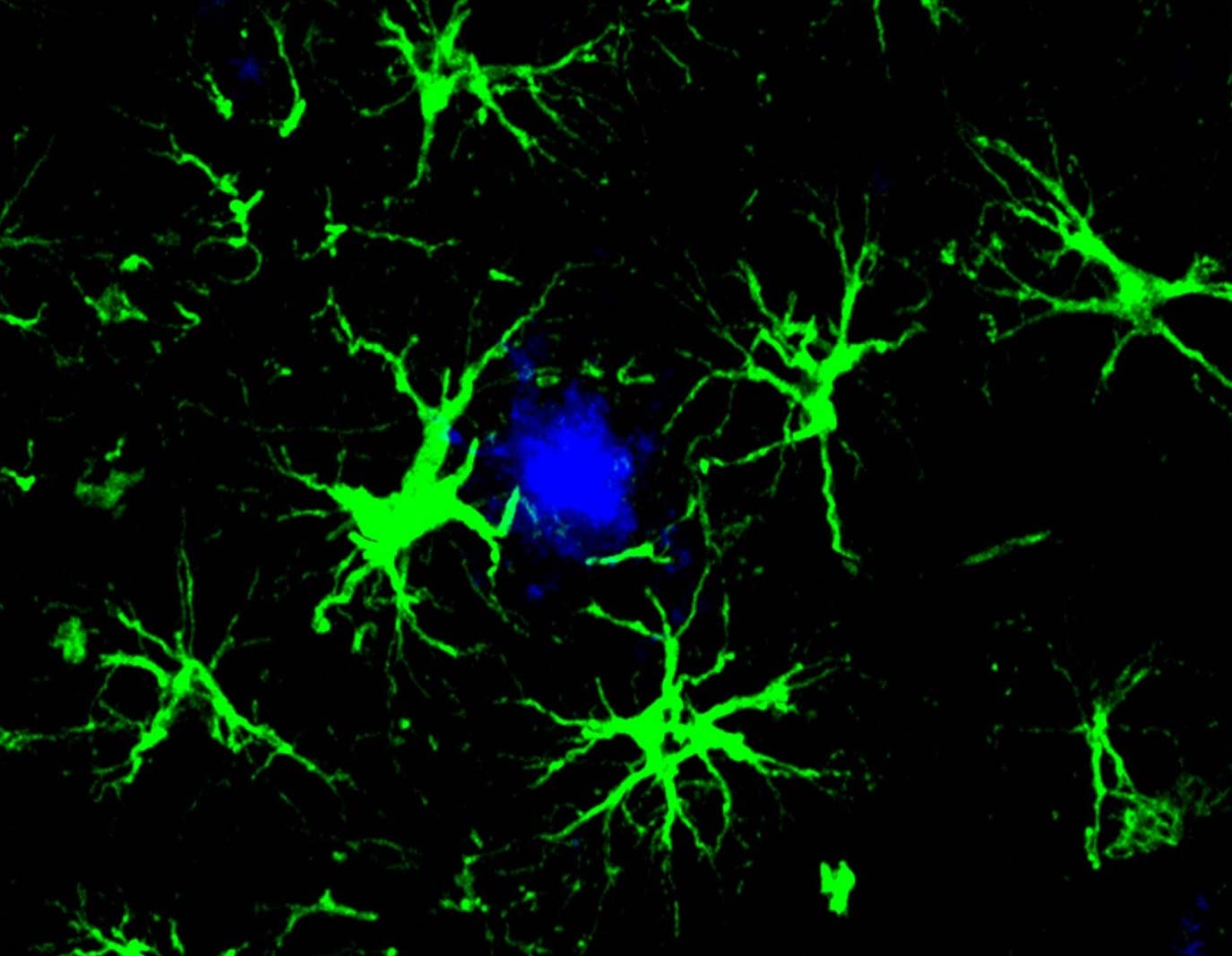

These Genetically Engineered Brain Cells Devour Toxic Alzheimer’s Plaques

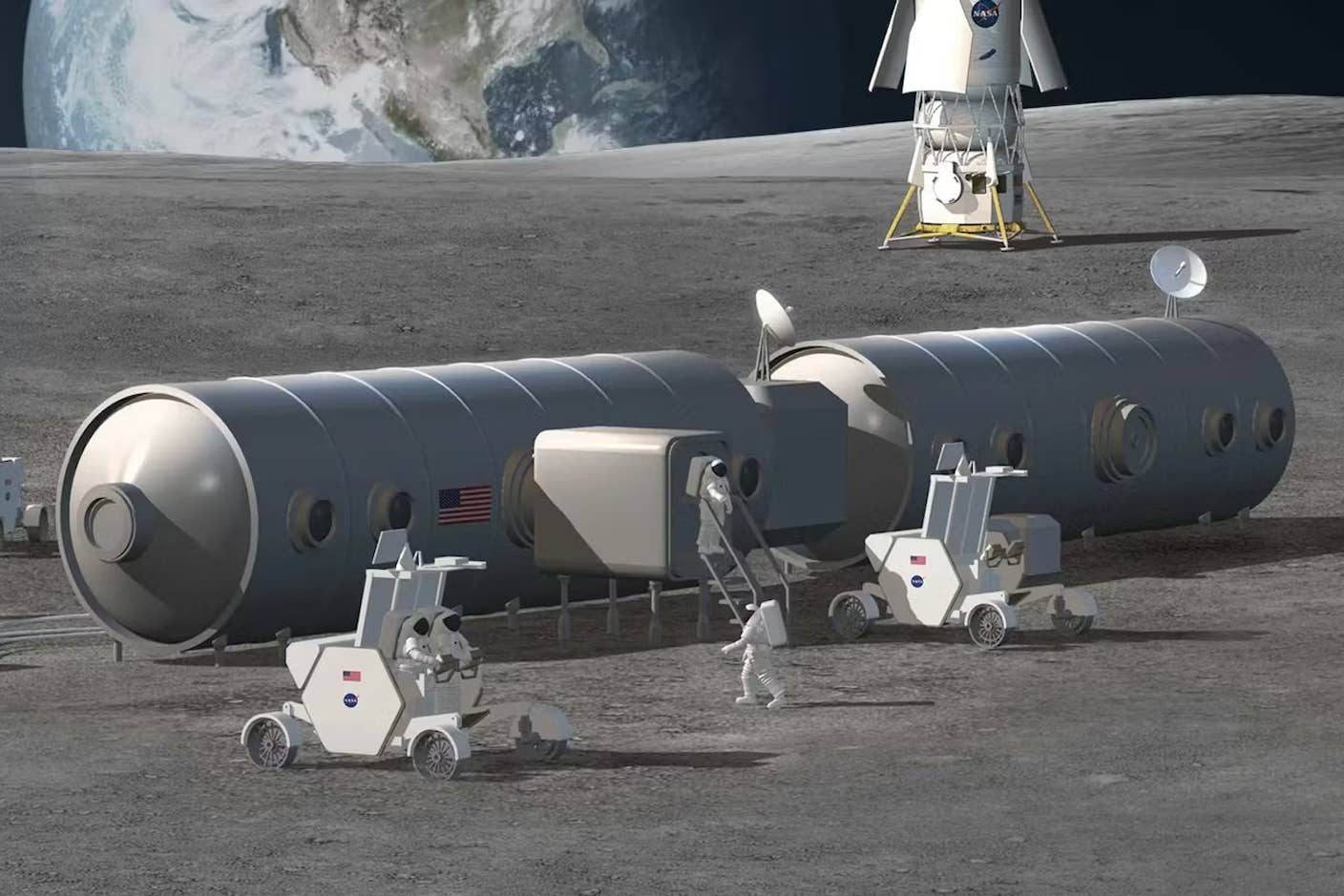

The US Plans to Break Ground on a Permanent Moon Base by 2030. Here’s What It Will Take.

In a First, Researchers Use Stem Cells and Surgery to Treat Spina Bifida in the Womb

What we’re reading