Cheap, Paper-Based Blood Test Costs Only Pennies, No Lab Equipment Needed

Share

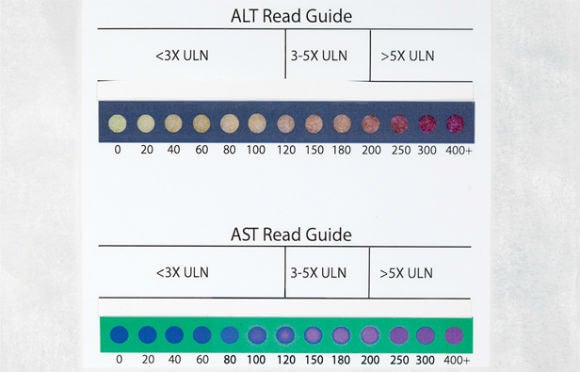

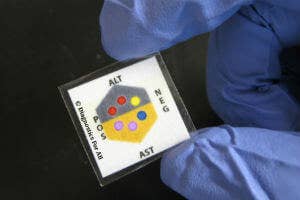

An inexpensive diagnostic test made from paper has been developed that can assess liver health in only 15 minutes and for only pennies a test. The test uses a single drop of blood from a fingerprick to measure the presence of liver enzymes, and doesn't require the presence of a laboratory, instrumentation, or syringes. If liver enzymes are present in the blood, wells within the paper will show a color change, which can be color matched to a scale to determine approximate degree of concentration.

Liver damage can be a consequence of taking antiretroviral drugs, which are prescribed to HIV patients. Because of the high HIV-infection rates in poor countries, liver problems are on the rise, so the ability to cheaply monitor blood is important to prevent potentially fatal side effects of the drugs meant to save people's lives.

The nonprofit captured some attention in 2009, when the potential of its research was promising. Now three years later, the organization recently announced that it is testing its paper-based chips with HIV patients in a Vietnamese hospital with hopes that the tests could be ready for the clinic by 2014, once regulatory approvals are obtained.

The postage stamp-sized paper diagnostics system was developed in the laboratory of Harvard Professor George Whitesides over five years ago. With funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Professor Whitesides started the non-profit organization, Diagnostics For All., and looked to improve the health of the poorest areas of the world.

The manufacturing process for the diagnostic tests are relatively easy, in that an ink jet printer using wax ink prints a pattern on two sheets of paper. One sheet contains reagents that react with lizer enzymes, the other dyes that change color if a reaction occurs. The two sheets are fused together by heating, so that channels or wells that can be used as miniaturized test tubes for reactions are produced.A plasma filter is added and the three are laminated together, and cut into squares.

When a drop of blood is placed onto the plasma filer, capillary action draws only plasma into the wells, and a reaction occurs if enzymes are present. Fifteen minutes later, a color change indicates the concentration range of enzymes presents. Though this can be spotted checked by eye, greater accuracy could be achieved using scanning the paper with a smartphone, which are incredibly prevalent throughout regions in which the kit would be used.

With this approach, the company believes it can manufacture up to a thousand tests a day at its current size.

While this particular test is rather straightforward in its design, it will require the same kind of testing for accuracy that any diagnostic test would undergo. For developing countries, the regulary hurdles aren't as severe, hence the timeline for getting them into the clinic.

This video from Innovators on Bloomberg TV does an excellent job explaining the technology and the researchers behind it:

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

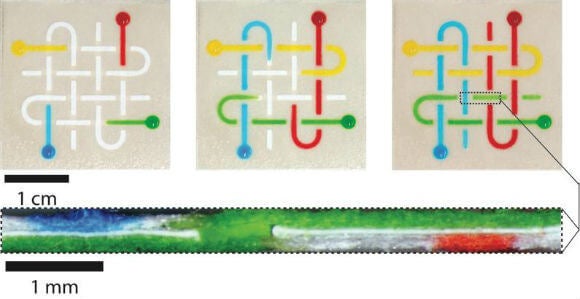

Professor Whitesides has been working in the area of microfluidics for years, and much more sophisticated designs (shown at the top of the page) can be achieved in which fluids can be drawn up into channels within paper and their flow controlled. The work being done by Diagnostics For All to get these tests into the practice will go a long way toward adoption of paper diagnostics.

The team is also working on malaria and dengue fever tests, according to Fast Co. Additional enzymes could be monitored as long as the proper reagent-dye combinations were cheap and stable on paper.

Though paper diagnostics has seen limited use to date, new fabrication techniques could open the door to a variety of diagnostic tests that could compete with standard ELISA testing, down the road. But the first step is to get a working kit adopted on a broad scale in order to show the viability of the approach.

To learn more about Professor Whitesides research in this area, check out his research group page on Paper Diagnostics Systems here.

David started writing for Singularity Hub in 2011 and served as editor-in-chief of the site from 2014 to 2017 and SU vice president of faculty, content, and curriculum from 2017 to 2019. His interests cover digital education, publishing, and media, but he'll always be a chemist at heart.

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading