Stem Cell Breakthrough in Mice Points Toward a Way to Repair Tissue in Humans

Some Spanish researchers were the first to turn mature cells into stem cells inside the body itself. They prompted the cells of adult mice to regain the ability to develop into any type of specialized cell, which is normally only briefly present during embryonic development. The results were published in September in the journal Nature.

Share

The field of regenerative medicine hopes one day to be able to produce new, healthy tissues and organs with patients’ own DNA by turning some of the patient's cells into stem cells that can then be guided to develop into healthy tissue. The cutting-edge process requires doctors to remove some of a patient's cells to do work on them in the lab.

But some Spanish researchers recently managed to turn mature cells into stem cells inside the body. They prompted the cells of adult mice to regain the ability to develop into any type of specialized cell, which is normally only briefly present during embryonic development. The results were published in September in the journal Nature.

The scientists likened the results to turning back the clock on dysfunctional human cells, giving them the chance to form again, erasing disease or other damage done over a lifetime.

“This change of direction in development has never been observed in nature,” said María Abad, the article’s lead author and a researcher in Manuel Serrano’s lab at the CNIO, as the center is known.

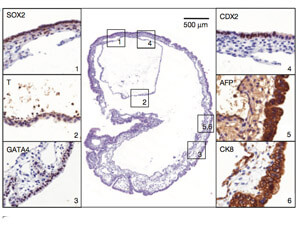

The experiment worked like this: Mice were genetically engineered to produce the genes that convert mature cells into stem cells. The transformation has previously only been successfully done in a Petri dish. When the genes were activated, the mice grew teratomas, or tumors made up of various tissue types akin to a failed embryo. The mice also began to circulate stem cells in their blood stream that were more diverse and plastic than even induced pluripotent stem cells, or iPSs.

“The next step is studying if these new stem cells are capable of efficiently generating different tissues such as that of the pancreas, liver or kidney,” said Abad.

Scientists have been able to reprogram adult cells to develop into the types of cells that form the different layers of an embryo. But they haven’t been able to produce the cells that make up tissue that sustains the development of a new embryo, like the placenta. The stem cells Abad and Serrano induced in mice did produce those cells. The stem cells they produced were described as "totipotent" rather than "pluripotent" for that reason.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

In fact—and this part is creepy—when placed in a mouse’s abdominal cavity, the stem cells formed an embryo-like structure, with the three types of cells organized in the right order. Like mouse embryos, the structures were hollow spheres filled with liquid.

Clearly the process needs some tweaks before it can be used on humans, lest it result in tumors like the teratomas that the lab mice developed.

Still, it has generated excitement from others in the field.

"It means that every cell in the body may have the potential to regenerate a new organism," George Daley, a stem-cell researcher at Children's Hospital Boston, told the Wall Street Journal.

Anthony Atala, director of Wake Forest’s Institute of Regenerative Medicine, told Singularity Hub that regenerating organs in place is the Holy Grail of curing diseased organs but also a very risky approach.

“It goes right along the lines of what we’re looking at with these strategies, in terms of how can you bring those cells to an earlier time point. But the challenge is how do you control the process to see that you don’t go too far back and start making tumors,” Atala said.

Serrano's lab plans to focus next on how doctors could target the process, in order to regenerate a specific area of damaged tissue without triggering tumors.

Images: anyaivanova / Shutterstock.com; Serrano and Abad courtesy CNIO; findings via Nature

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

What we’re reading