Power Storage, Missing Link in Path to Renewables, Gets a Mandate in California

The inability to store electrical power has become more important as the developed world has begun to try to adopt cleaner energy sources, such as solar and wind power. The sun isn’t always shining and the wind isn’t always blowing, but people and factories always need electricity. But energy storage is getting its mainstream debut in California. The state has mandated that by 2024, its major utilities provide 1,325 megawatts of storage, which is slightly more than what a single major power plant produces and about a fifth of a percent of what the state used on average per day, according to the most recent state statistics.

Share

Electricity, despite having transformed nearly every aspect of life on Earth, remains a technology with some significant limitations. More than half of the energy that goes into producing electricity is lost, and even the energy that is successfully converted into electricity is a use-it-or-lose it proposition, so much of it ends up wasted as well.

The inability to store electrical power has become more important as the developed world has begun to try to adopt cleaner energy sources, such as solar and wind power. The sun isn’t always shining and the wind isn’t always blowing, but people and factories always need electricity.

But energy storage is getting its mainstream debut in California. The state has mandated that by 2024, its three major utilities provide 1,325 megawatts of storage, roughly equivalent to what one major power plant produces and about a fifth of a percent of what the state used on average per day, according to the most recent state statistics.

“Storage is a game-changer that can help people manage their energy use and expand the capacity of renewable resources to provide power to homes and businesses. This decision will spur investment and innovation in energy storage and help Californians unleash their creative and economic power,” Catherine Sandoval, a member of the California Public Utility Commission that issued the new requirement, said in a news release.

Storing electrical power isn't technically difficult; the challenge is doing it at a price that makes it worthwhile as a regular practice. California hopes to push the industry to get there faster, just as it did in 2002 with its early requirement that utilities use renewable sources for 20 percent of the power they sell.

Worldwide, there’s only enough storage on the grid to handle 1 or 2 percent of what’s generated, according to Gregg Maryniak, who leads Singularity University’s Energy and Environment instruction.

“It’s really important that there’s that mandate. It’s an important and progressive step to have for storage,” he said.

The most common method of storing electrical power involves pumping water uphill when power is abundant, and then using the water to generate power hydroelectrically when power is needed. The new rule limits how much of this type of storage utilities can count toward the mandate. Other methods in use also rely on particular types of geography to work, sidelining them from wider use.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The renewable energy industry has had stronger motivation than conventional utilities to make storage work.

Concentrating solar power arrays, which tap the thermal energy of the sun, also sometimes use molten salt to store heat for later use. The salt is stored in tanks and used to drive a steam turbine when energy is needed and the sun isn’t shining.

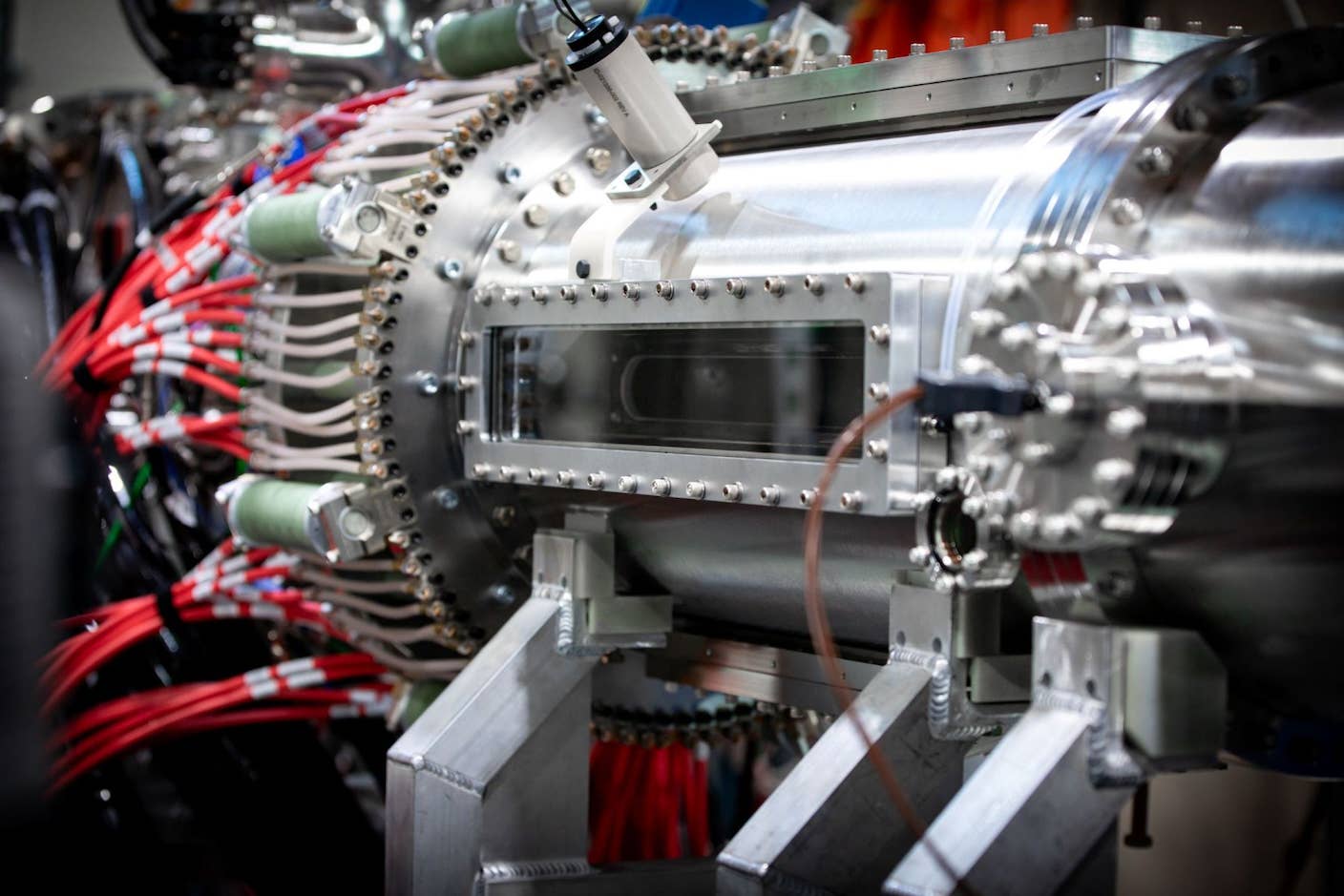

There are new methods in the making as well. Halotechnics, based in Emeryville, Calif., has developed a glass with an even higher melting point than salt in order to increase storage efficiency. Berkeley-based Lightsail has pioneered more efficient methods to compress, and later decompress, air as a way to store electricity.

These companies and others will get a boost from California’s new requirement. And if storage works in the Golden State, similar requirements will likely march across the rest of the U.S. and Europe.

But only time will tell: The storage facilities aren’t required to be operational until 2024.

Photos:

Parabolic trough concentrating solar array by Z22 via Wikimedia Commons

Castaic Power Plant, a pumped-storage plant near Los Angeles: State of California via Wikimedia Commons

Solana power plant, an Arizona plant that uses molten-salt storage, Concentrating Solar Power Alliance

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

Startup Zap Energy Just Set a Fusion Power Record With Its Latest Reactor

Scientists Say New Air Filter Transforms Any Building Into a Carbon-Capture Machine

Investors Have Poured Nearly $10 Billion Into Fusion Power. Will Their Bet Pay Off?

What we’re reading