Human Skin Grown From Stem Cells Replicates The Real Thing

Researchers have successfully produced skin in the lab that reproduces the skin barrier. The advance presents a viable alternative to animal testing for cosmetics.

Share

It’s much easier to defend the use of animal testing for medical research than for cosmetics testing. Yet many cosmetics companies continue to test on animals to ensure that their products don’t produce negative outcomes for their human customers.

Even as medical researchers produce “organs on a chip” to help with drug testing, developing human skin for cosmetics testing has remained elusive. Simply cultivating skin cells in a petri dish doesn’t work because the cells don’t proliferate enough to be useful for many tests. And fabricating skin cells from stem cells has also fallen short, because the epidermal cells grown in a lab culture don’t produce the same barrier that human skin uses to keep moisture in and toxins out.

Researchers at King’s College London and the San Francisco Veteran Affairs Medical Center report they have cleared those hurdles.

“Our new method can be used to grow much greater quantities of lab-grown human epidermal equivalents, and thus could be scaled up for commercial testing of drugs and cosmetics,” said Theodora Mauro, who led the San Francisco team.

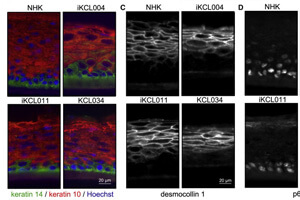

Using both human embryonic stem cells and induced pluripotent stem cells, they developed keratinocytes, the cells that make up the skin’s protective barrier. They positioned the cells into layers while gradually reducing the humidity in the cell culture, and ended up with a stratified epidermis with skin barrier properties similar to those of normal skin. (Essentially, different proteins dominated in each layer.)

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The method could viably produce enough skin samples to be used commercially for drug and cosmetics testing, according to the researchers.

An added benefit: Making the skin from stem cells means that particular diseases could be intentionally produced for study, including common skin ailments like dermatitis in which a defective skin barrier means that toxins cannot be handily repelled and become irritants. Admittedly, these diseases are neither life-threatening nor medically exciting, but they are a big nuisance for those who suffer from them. Some, like atopic dermatitis, remain poorly understood.

“The ability to obtain an unlimited number of genetically identical units can be used to study a range of conditions where the skin’s barrier is defective due to mutations in genes involved in skin barrier formation. We can use this model to study how the skin barrier develops normally, how the barrier is impaired in different diseases and how we can stimulate its repair and recovery,” Mauro said.

Use of stem cell-based proxies for specific human organs, both to study disease behavior and to test drugs, is a rapidly growing market. In many cases its benefits are so hypothetical — eliminating negative outcomes that would, statistically, have happened if in vitro organ tissue hadn’t been used — that they go unheralded. It will be interesting if the benefits of lab-made skin — potentially vastly reduced animal testing laboratories — garner more attention for the technique.

Photos: Tania Zbrodko / Shutterstock.com, Petrovo, Mauro, Ilic et al, courtesy Stem Cell Reports

Cameron received degrees in Comparative Literature from Princeton and Cornell universities. He has worked at Mother Jones, SFGate and IDG News Service and been published in California Lawyer and SF Weekly. He lives, predictably, in SF.

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 21)

What the Rise of AI Scientists May Mean for Human Research

This ‘Machine Eye’ Could Give Robots Superhuman Reflexes

What we’re reading