First Patient Receives Stem Cell Treatment for Degenerative Eye Disease

Share

Since stem cells were first hailed as a potential cure for a variety of diseases, we have witnessed setbacks, controversies, and failures. Now, however, human trials for the use of stem cells in treating degenerative eye disease have received the green light from an oversight committee in Japan after they agreed that the proposed treatment is safe.

The trial is especially significant because instead of employing controversial embryonic stem cells, researchers will instead use induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells—that is, stem cells derived from the patient's own body (in this case, the skin).

With the approval, a team of doctors, led by Dr. Yasuo Kurimoto, transplanted retinal tissue grown from a patient’s own induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells in the hopes of treating her eye disease. The elderly woman suffers from age-related macular degeneration, one of the most common causes of visual impairment in people over 50.

The disease results when the retina detaches from the underlying tissue because of either the accumulation of cellular debris or the over-growth of blood vessels.

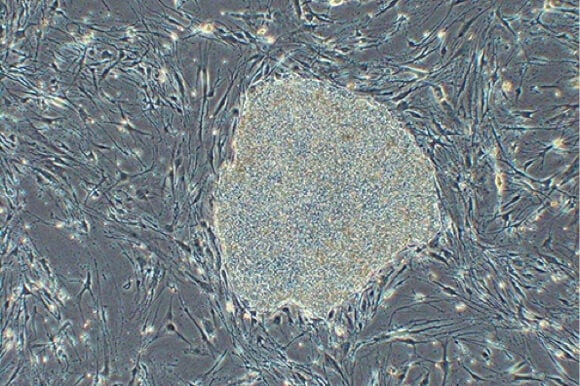

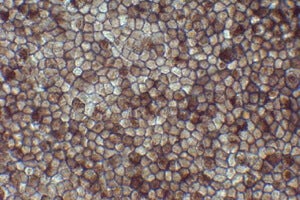

To generate the transplanted tissue, Dr. Masayo Takahashi, from the Laboratory for Retinal Regeneration at the RIKEN Center for Developmental Biology in Kobe, Japan, took skin cells from the patient and coaxed them into pluripotent cells. These cells were then manipulated to become retinal tissue that were grown as thin sheets and used to replace the patient’s damaged tissue.

Though this treatment may not fully restore the patient’s vision, it is expected to at least prevent her from going fully blind. It also serves as an important proof-of-principle that iPS cells are safe and effective for use in treating degenerative eye disease.

Before human trials, the researchers tested the safety of iPS cells in mice and monkeys. They found tissue made from iPS cells did not cause immune reactions because it came from the same animal it was transplanted into. Further, they didn’t find evidence the cells grew into cancerous tissue, a serious concern regarding the use of stem cells.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Like embryonic stem cells, iPS cells have the potential to become any type of cell in the body. However, clinical use of iPS cells gets around the ethical and religious objections to the production and subsequent destruction of human embryos to harvest stem cells.

When President Obama loosened federal restrictions on the use of embryos for research in 2009, he only removed the ban on embryos left over from in vitro fertilization (IVF) treatments. The Bush-era ban on the creation of embryos strictly for research is still in effect.

This is why research into the feasibility of iPS cells for therapeutic uses has received much support in the past few years. Indeed, the 2012 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Dr. Shinya Yamanaka and Dr. John B. Gurdon for their discovery that differentiated cells could be induced to become pluripotent cells.

Now, two years later, we’re witnessing one of the first clinical applications of iPS cells.

Of course, only time will tell whether these cells live up to their potential to yield revolutionary treatments for a host of human diseases. For now, it will be important to continue funding these types of studies whenever they show promise in the clinic.

Image Credit: RIKEN

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

This Light-Powered AI Chip Is 100x Faster Than a Top Nvidia GPU

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 20)

What we’re reading