There’s a Robot Waiting to Treat Your Predicted Heart Attack (Interview)

Share

Habib Frost, Medical Innovator & Entrepreneur

Copenhagen, Denmark

Like the swinging of a pendulum, the mind of an inventor is often inspired by the voice of the critic; a filter that questions everything it is presented, and importantly so.

Though there is no formal vocational track to becoming an inventor, the call to invent was deep within Habib Frost from a young age. Growing up in Denmark, Habib had an innate interest in technology and the human body. When his parents would leave the house, Habib enjoyed picking apart whatever object of the moment grabbed his interest. By age 17, Habib began medical school in his hometown of Copenhagen and graduated at 23, setting a new record as the youngest medical doctor in Denmark.

Throughout medical school, Habib began noticing that things were not working out as well in the medical landscape as he hoped—people weren’t surviving as often as he had imagined. Specifically, he took note of the low survival rate of cardiac arrest patients treated with a defibrillator—with a meager 1 in 10 making it to hospital discharge.

One day in particular during his training forced Habib to pause, reexamine, and ultimately redirect his path in medicine. During that day, a 4-month-old girl went into cardiac arrest, and they couldn't save her. “After half an hour of trying to save her, my mentor said, ‘We'll figure out what's wrong with her. She's dead.’ Later that same day, we had a young woman also suffer a cardiac arrest. The defibrillator did not have an effect on her either.”

Habib took the next few days to contemplate what he really wanted to do, and from this introspection the ideas for Neurescue emerged. Over 2 years later, Neurescue is now a venture-backed startup using emerging technologies to develop a new medical device that can vastly improve the resuscitation and survival rates of cardiac arrest.

Upon beginning his new endeavor, Habib’s colleagues thought he was insane, "Why would you be able to come up with anything new when people have been trying to solve the same problem for the last 40 years?" became a common remark Habib heard.

But undeterred, and after roughly 320 attempts of scouting the technology landscape, and mixing and matching, Habib invented an entirely new solution, pitched it to just one venture capital firm in Denmark, and got funding—all within his last year of medical school. The product is a lightweight device for medical professionals treating patients in cardiac arrest that combines machine intelligence with modern micro-sensors and actuators to supplement the human capability of those practitioners.

“What we've been able to come up with is a new treatment that wasn't possible with a machine, robotics, or human skill alone. But combining human skill and machine technology opens up a whole new plethora of treatments.”

Habib’s ambition for the future of medical innovation holds more. A lot more. He’s dreaming of fully automated procedures previously performed by medical professionals with years, decades, of skilled training. “At some point, you wouldn't even need the medical person at all.”

Sitting down with Habib Frost felt a little like interviewing an inventor of the early 1910s predicting the world we live in today—delightfully terrifying, in the best way imaginable.

IS THERE VALUE IN RECEIVING TREATMENT FROM WARM HANDS?

One of the wisest decisions we can make is to acknowledge that modern robotics can deliver the same actions of compassion as warm hands, even though there might not be a beating heart behind them. – Habib Frost

Alison: You’re in a moment of distress and a machine comes to take care of you. As we move towards increased medical automation, will patients still need the one-on-one human interaction to calm and comfort them during treatment or diagnosis?

Habib: I think we simply cannot scale the current model of medicine. Even in some of the wealthiest countries, we still don’t have enough time with “warm hands” for patients.

We will be able to afford much more if we look at how we can relieve these very busy hands with automated systems. So, instead of having a nurse transporting food, giving medication, and doing charts, that nurse would have time for a conversation with the patient who just got a new piece of vital information, to see how that person feels about it.

Having a system that performs these vital measurements and procedures—these very repetitive procedures—will create more time to have those conversations, and more time for that compassion. I do believe that eventually robots will also be able to deliver this compassion.

HOW TO SCALE MEDICAL INNOVATION GLOBALLY

The increase in automation, sensors, and robotics doesn’t necessarily correlate with increase in price. Quite the contrary, it is having people with 15 years of training behind them—and that being a requirement—that is what prevents medical innovation from scaling to low-income countries. –Habib

Alison: If we live in a world where an emergency medical robot takes action in response to a signal sent by your cardiac implant, which is predicting the heart attack you’re about to have, how will we disseminate this across the world to provide equal treatment globally?

Habib: Carrying out an operation with anesthesiologists, surgeons, surgical nurses can easily cost $50,000 per procedure. That doesn’t scale. An autonomous surgical system performing that same procedure using only $2 or $3 in electricity—this scales.

Alison: It’s interesting, because this is the very antithesis of what we're taught growing up, which is to become as skilled as possible, and that that is where the most value and money is. This would really turn that model upside-down.

Habib: Right now people believe that you need hands that have 15 years of training before you can scale something to high-income and low-income countries—that is actually what's preventing us from having this new technology in high-income and low-income countries.

I think disrupting this idea that what a medical doctor can do is somehow holy is greatly important. This means removing the notion that there’s something magical happening with human hands—or something magical happening with the human mind with only 20 seconds to spare. Seeing that machines can perform many of these tasks is going to be essential to delivering scalable technology globally.

We need to be aware of how much is repetitive in medical practice. Most of the tasks are so repetitive and don’t require ingenuity during the daily practice. I think this old mindset is what is keeping us back.

INNOVATION WHEN YOU CAN’T “FAIL FAST”

So the question becomes, how do you promote innovation in highly regulated fields, but at the same time, not stifle the innovation? -Habib

Alison: During the innovation processes it’s encouraged to “fail fast,” but as a doctor, you can’t simply “fail fast” and move on to your next case. How does this impact medical innovation and the early iteration processes?

Habib: You have to be very respectful of the best practice, and deliver that to your patient, but also influence and change the landscape by having an experimental mind. What regulatory bodies do is wonderful—they ensure our safety—but at the same time it can stand in the way of great innovation. And that challenge can be hard to tackle.

I actually think that medical training should look more and more like engineering.

Medical school and engineering can almost be opposite. In engineering, you start with the math and physics, and you build your way up, and you constantly ask, "What can I create that doesn't exist yet?" Whereas with medical research the question is usually, "What can I discover that’s waiting to be unveiled?"

It’s going to become increasingly important for medical professionals to have that innovation mindset, to have that entrepreneurial spirit.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

MINDSET AS A BARRIER TO ENTRY

Mindset can make you hold back some of your greatest ideas. Once you're liberated externally, your own internal mindset and ideas also get liberated. –Habib

Alison: Was there a moment in your life when an internal liberation to your thinking occurred? Where you woke up to the kind of work you wanted to do?

Habib: When I had to decide my bachelor’s degree project, at first I couldn't come up with anything. I didn’t think I had it in me to come up with some new, wonderful hypothesis or invention. When I was around people who wanted to keep me down, my own drive was kept down as well.

There was a flipping point where I suddenly went from not thinking, not believing in myself that I could come up with any ideas, to suddenly having many. Then it was a question of choosing which one to act on. Once I started letting myself have bold ideas, they've been increasing in quality and quantity ever since.

When I started having that diversity of international friends and students with different perceptions of what you can do, and what kind of ambitions you can go for, that also was that exact moment when I also liberated my own thoughts and my capabilities for ideas.

WHAT DOES EMERGENCY MEDICINE LOOK LIKE IN 2020?

Your personal implant or wearable sensors will predict that you're going to be in distress 10 to 15 minutes from now, based on an evaluation of your physiological state, and will dispatch a self-driving system (or UAV) to treat your emergency condition before it happens. –Habib

Alison: If you were to look forward five years from now to 2020, do you have a prediction or a vision of how emergency medical respondents may look different?

Habib: I think we'll have an increased awareness of the fact that our mental processing plummets in these emergency situations. We demand so much from these people in the field.

You have to almost be ADHD to thrive in it. Entrepreneurs and emergency physicians actually have quite a lot in common. You have a risk agnostic gene that can thrive in a very high-risk situation, a very rapid situation, and they wouldn't be suited to work with the same patients over 20, 30 years like some other physicians might.

Currently, we have physicians and nurses performing emergency procedures and making emergency decisions on their own. Eventually this can be partially replaced by technology performing these procedures, and followed by having more and more autonomous therapeutic circles, where technology actually does the procedure.

The experience in the future will be that you have automated service of, let's say, one person and one autonomous emergency robot that will be by your door, ready to pick you up for the heart attack you're about to have.

HUMAN ERROR UNDER PRESSURE

As passionate and dedicated as our medical professionals are today, I only think we can do our patients justice by augmenting those capabilities with the new technologies around us.

–Habib

Alison: On the subject of using technology to decrease human error, what happens to the human mind when making a life or death decision in those condensed decisive moments?

Habib: Your IQ drops, your memory falters, even the position of your hand and body movements are more prone to error. You're at high risk of getting hurt. For example, I‘ve tried to be out on the ice retrieving a patient; I’ve tried to be inside a building where there's a risk of collapse. We shouldn't actually send people inside burning houses, or rubble, or out on ice for that matter. We shouldn't use people in high-risk situations.

There eventually will be increased awareness that the decisions physicians make should not be made by the processing capability of the human mind alone. We simply cannot allow these decisions to happen by the skill set of the human alone.

Connect with me on twitter @DigitAlison or @SingularityHub, or follow the full series here. Learn more about Singularity University's Graduate Studies Program here.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Alison tells the stories of purpose-driven leaders and is fascinated by various intersections of technology and society. When not keeping a finger on the pulse of all things Singularity University, you'll likely find Alison in the woods sipping coffee and reading philosophy (new book recommendations are welcome).

Related Articles

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through December 13)

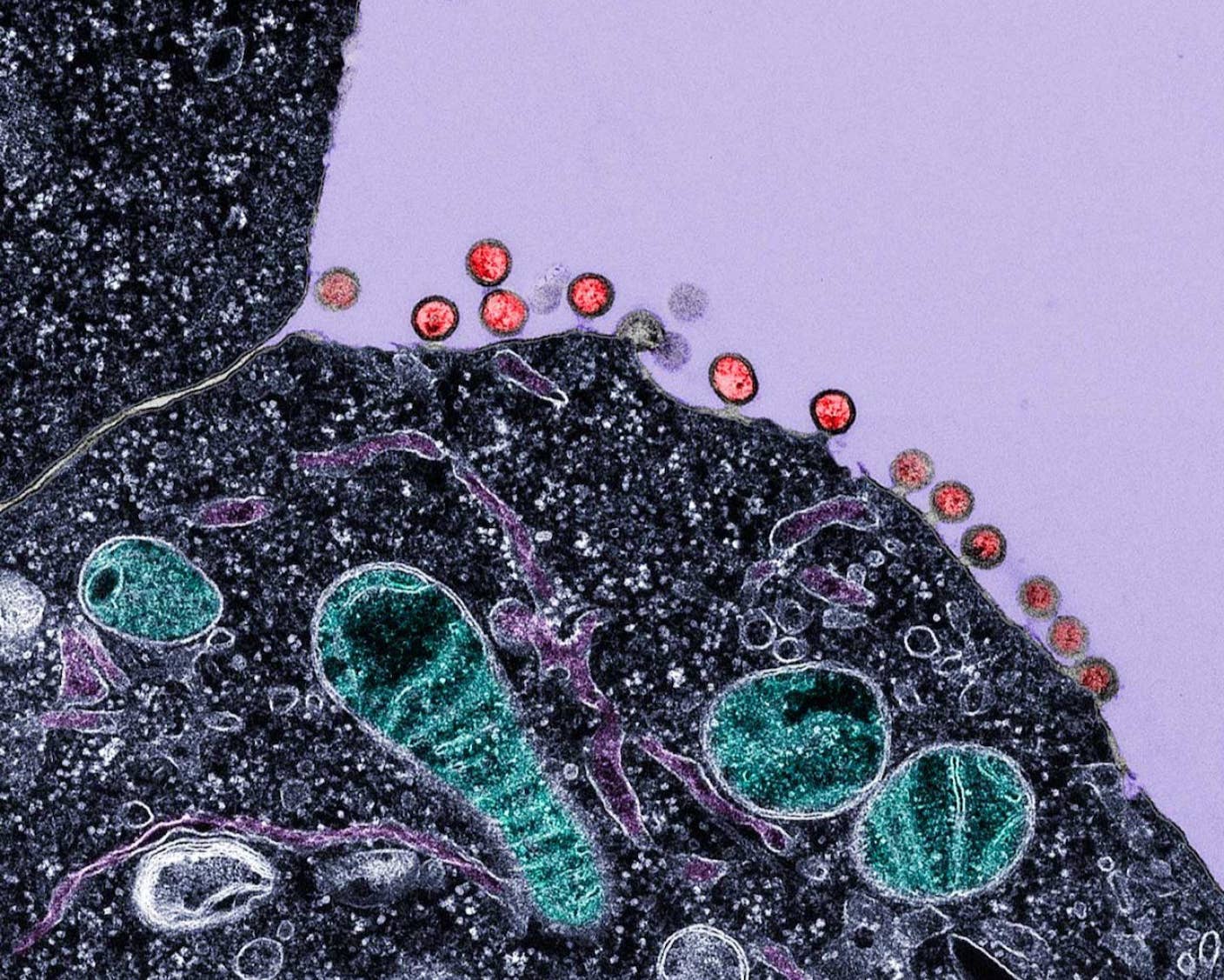

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

How Scientists Are Growing Computers From Human Brain Cells—and Why They Want to Keep Doing It

What we’re reading