3 Ways Exponential Technologies Are Impacting the Future of Learning

Share

“Simply put, we can’t keep preparing children for a world that doesn’t exist.”

-Cathy N. Davidson

Exponential technologies have a tendency to move from a deceptively slow pace of development to a disruptively fast pace. We often disregard or don’t notice technologies in the deceptive growth phase, until they begin changing the way we live and do business. Driven by information technologies, products and services become digitized, dematerialized, demonetized and/or democratized and enter a phase of exponential growth.

Nicole Wilson, Singularity University’s vice president of faculty and curriculum believes education technology is currently in a phase of deceptive growth, and we are seeing the beginning of how exponential technologies are impacting 1) what we need to learn, 2) how we view schooling and society and 3) how we will teach and learn in the future.

Watch Nicole Wilson, VP of Faculty and Curriculum at Singularity University discuss the three ways which exponential technologies are impacting how we teach and learn.

Exponential Technologies Impact What Needs to be Learned

In a 2013 white paper titled Dancing with Robots: Human Skills for Computerized Work, Richard Murnane and Frank Levy argue that in the computer age, the skills which are valuable in the new labor market are significantly different than what they were several decades ago.

Computers are much better than humans at tasks that can be organized into a set of rules-based routines. If a task can be reduced to a series of “if-then-do” statements, then computers or robots are the right ones for the job. However, there are many things that computers are not very good at and should be left to humans (at least for now). Levy and Murnane put these into three main categories:

Solving unstructured problems.

Humans are significantly more effective when the desired outcomes or set of information needed to solve the problem are unknowable in advance. These are problems that require creativity.

Working with new information.

This includes instances where communication and social interaction are needed to define the problem and gather necessary information from other people.

Carrying out non-routine manual tasks.

While robots will continue to improve dramatically, they are currently not nearly as capable as humans in conducting non-routine manual tasks.

In the past three decades, jobs requiring routine manual or routine cognitive skills have declined as a percent of the labor market. On the other hand, jobs requiring solving unstructured problems, communication, and non-routine manual work have grown.

The best chance of preparing young people for decent paying jobs in the decades ahead is helping them develop the skills to solve these kinds of complex tasks.

What are these skills exactly?

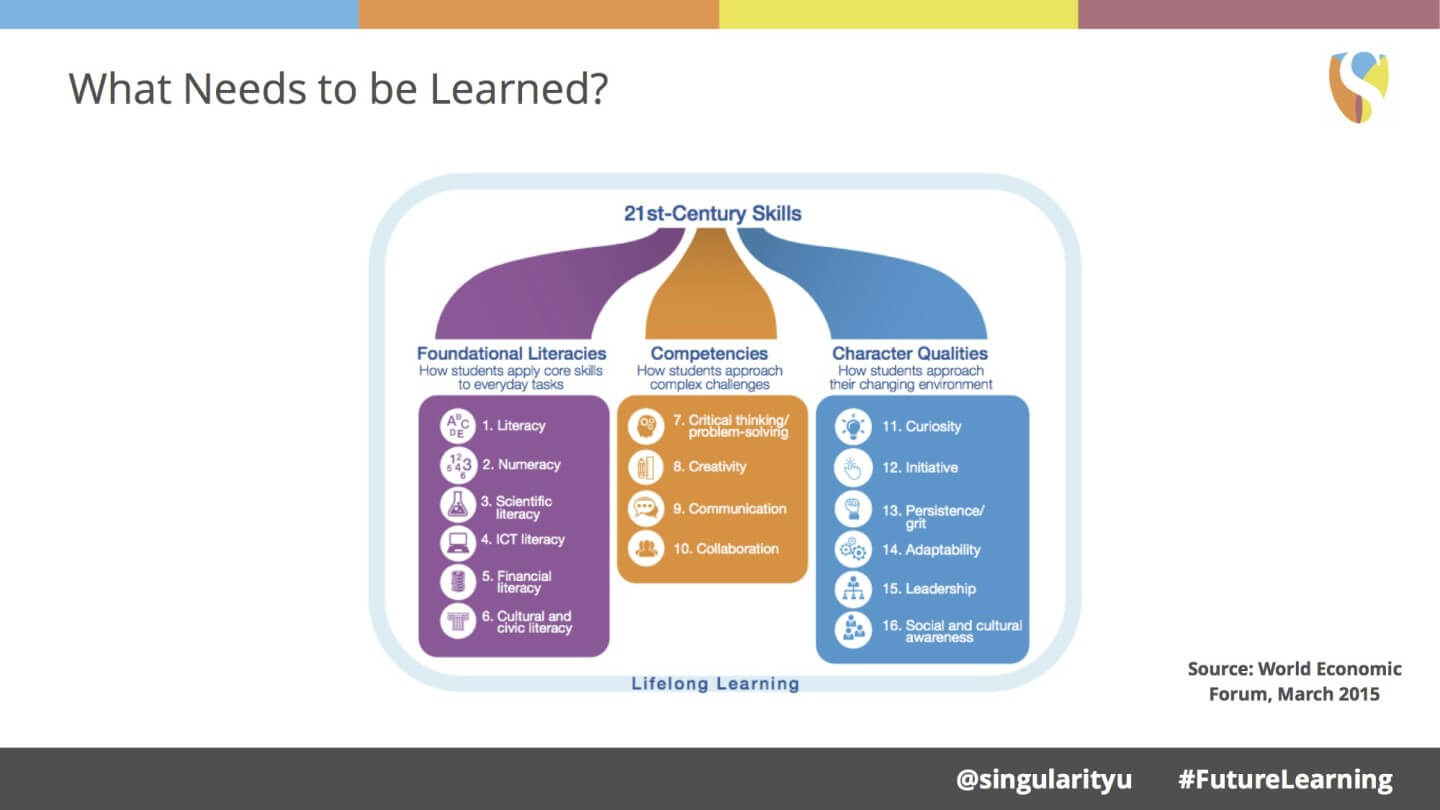

In March, the World Economic Forum released their New Vision for Education Report, which identified a set of “21st century skills.” The report broke these into three categories: ‘Foundational Literacies’, ‘Competencies’ and ‘Character Qualities’.

The foundational literacies are the “basics.” Reading, writing, sciences, along with more practical skills like financial literacy. Even in a world of rapid change, we still need to learn how to read, write, do basic math, and understand how our society works.

The competencies are often referred to as the 4Cs — critical thinking, creativity, communication and collaboration — the very things computers currently aren’t good at. Developing character qualities such as curiosity, persistence, adaptability and leadership help students become active creators of their own lives, finding and pursuing what is personally meaningful to them.

Exponential Technologies Impact How We View Schooling and Society

In her book, Now You See It, Cathy N. Davidson, co-director of the annual MacArthur Foundation Digital Media and Learning Competitions, says 65 percent of today’s grade school kids will end up doing work that has yet to be invented.

Davidson, along with many other scholars, argues that the contemporary American classroom is still functioning much like the classroom of the industrial era — a system created as a training ground for future factory workers to teach tasks, obedience, hierarchy and schedules.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

For example, teachers and professors often ask students to write term papers. Davidson herself was disappointed when her students at Duke University turned in unpublishable papers, when she knew that the same students wrote excellent blogs online.

Instead of questioning her students, Davidson questioned the necessity of the term paper. “What if bad writing is a product of the form of writing required in school — the term paper — and not necessarily intrinsic to a student’s natural writing style or thought process? What if ‘research paper’ is a category that invites, even requires, linguistic and syntactic gobbledygook?”

And if term papers are starting to seem archaic, formal degrees might be the next to go.

Getting a four-year degree in any technology field makes little sense when the field will likely be radically different by the time the student graduates. Today, we’re seeing the rise of concepts like Mozilla's “open badges” and Udacity’s “nanodegrees.” Udacity recently reached a billion-dollar valuation, partially based on the promise of their new nanodegree program.

Exponential Technologies Impact How We Teach and Learn

Technologies like artificial intelligence, big data and virtual and augmented reality are all poised to change the way we teach and learn both in the classroom and outside of it.

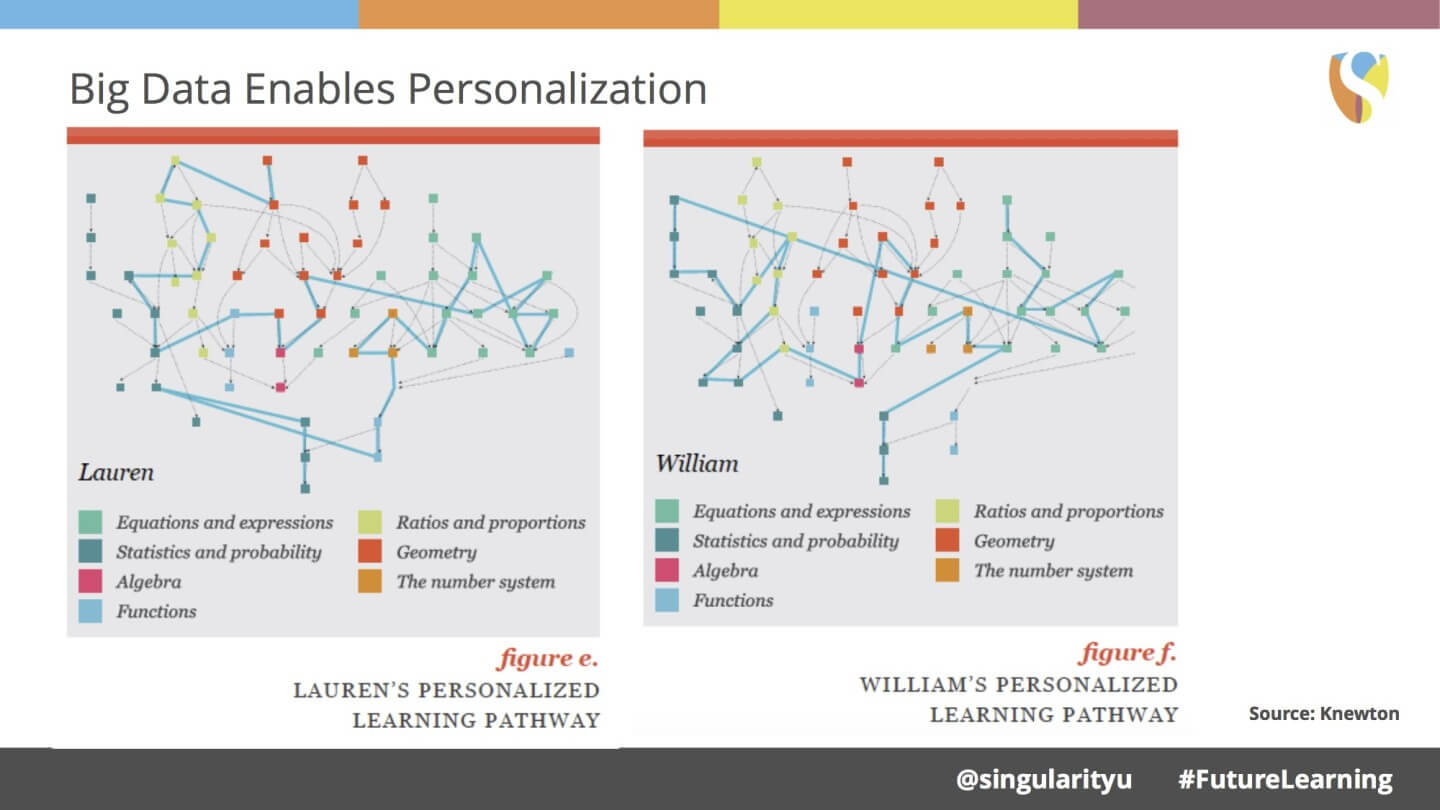

The ed-tech company Knewton focuses on creating personalized learning paths for students by gathering data to determine what each student knows and doesn’t know and how the student learns best. Knewton takes any free, open content, and uses an algorithm to bundle it into a uniquely personalized lesson for each student at any moment.

And while there’s no lack of enthusiasm around the potential of using virtual reality to change education, we are just seeing the first baby steps toward what will eventually be the full use of the technology. Google Expeditions, which aims to take students on virtual field trips and World of Comenius, a project which brought Oculus Rift headsets to a grammar school in the Czech Republic to virtually teach biology and anatomy are just two examples of many teams going through the process of trial and error to define what works for education in VR and what doesn’t.

It’s clear that technologies undergoing exponential growth are shaping the skills we need to be successful, how we approach education in the classroom, and what tools we will use in the future to teach and learn. The bigger question is: How can we guide these technologies in a way that produces the kind of educated public we wish to have in the coming years?

Sveta writes about the intersection of biology and technology (and occasionally other things). She also enjoys long walks on the beach, being underwater and climbing rocks. You can follow her @svm118.

Related Articles

Autonomous AI Agents Have an Ethics Problem

Sparks of Genius to Flashes of Idiocy: How to Solve AI’s ‘Jagged Intelligence’ Problem

Researchers Break Open AI’s Black Box—and Use What They Find Inside to Control It

What we’re reading