China’s Curious Dream of Floating Nuclear Plants on the Ocean

Share

The family of nuclear reactors found on the seven seas is about to grow—China recently announced plans to build a floating, ship-based nuclear power plant. Construction of the ship will begin next year, and if things go to plan, it will start producing electricity by 2020.

If you’re wondering whether that’s such a good idea—you probably aren’t alone.

But nuclear reactors at sea aren’t uncommon. The US Navy alone currently has around 100 reactors powering its submarines and aircraft carriers. However, the idea of floating nuclear reactors generating energy for uses other than powering their home vessel is relatively untested.

China isn’t the only country exploring nuclear power plants at sea.

Russia’s ‘Project 20870’ involves placing two nuclear reactors on 140-meter long, 30-meter wide barges. The plan would use these nuclear barges’ 300MWt (thermal energy production) or 70 MWe (electrical energy production) to power remote cities and industrial sites throughout the Russian Arctic.

Both projects might owe inspiration to the first ship-based nuclear power station, which was decommissioned in 2014. The American MH-1A, ‘Sturgis’, was constructed back in the 1960s and towed to the Panama Canal region, where it supplied essential electricity between 1968 and 1976.

It’s estimated the MH-1A helped bring up to 15 more ships through the canal a day than would otherwise have been possible.

A flexible platform for the future?

What are the advantages of putting nuclear reactors on ships? China General Nuclear, the company behind the new project, stresses the flexible nature of a ship-based nuclear reactor.

“The 200 MWt (60 MWe) reactor has been developed for the supply of electricity, heat and desalination and could be used on islands or in coastal areas, or for offshore oil and gas exploration.”

Other potential uses could be for new, large-scale industrial installations and flexible emergency power to regions in the event of natural disasters such as earthquakes or tsunamis.

According to Jacopo Buongiorno, an MIT professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering, building smaller sea-based nuclear power plants could also help dramatically lower construction cost and time—it can take decades to build a large nuclear power plant on land.

Concept drawing of an offshore nuclear plant. The floating structure would house staff and include a helipad, like an offshore oil rig. Image Credit: MIT

Buongiorno and his team at MIT have suggested placing reactors on platforms similar to those used for deep-sea oil drilling. The plants would be situated between 8 and 12 miles from the coast at a depth of at least 100 meters. Power cables would run to switchyard facilities situated on land.

Being placed so far from land would help protect the plants against earthquakes and tsunami waves, which are relatively small so far out.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The MIT team describes offshore nuclear power generation as “a potential game changer” in terms of nuclear power economics as it allows for assembly-line-like production of units.

China betting on nuclear

The ocean-based nuclear power plant is one of a string of new types that was outlined in the China’s 13th five-year plan. The plan underlines that China aims to adopt innovative energy technologies, and that the country will build at least 100 new nuclear power reactors in the coming ten years.

It appears the country will use nuclear power to help reduce its current heavy reliance on coal, and in doing so, dramatically lower emissions of CO2 and air pollutants, which have reached health-threatening levels in many areas. China will invest more than a trillion dollars in nuclear energy over the coming years. In time, it’s hoping to recuperate some of that by becoming a leading global exporter of nuclear technology.

The dangers of going to sea

While there are advantages of placing nuclear power plants on water, as you might expect, the new projects are not without their critics.

Greenpeace has voiced concern about what effect massive storms could have on ocean-based nuclear reactors. Others worry ocean-based reactors would be more susceptible to terrorist attacks.

Operating nuclear reactors in an Arctic climate is complicated to say the least, and another concern is that barges like those used in the Russian project might not be as protected from earthquake or tsunamis as reactors further out at sea.

It makes plenty of sense to carefully weigh potential risks and benefits.

One use case, however, does show that disciplined operators can take nuclear to the oceans. The US Navy has logged more than 5,400 reactor years and traveled more than 130 million miles. They have sailed all the seven seas, including some of the most hostile environments, without any publicized accidents.

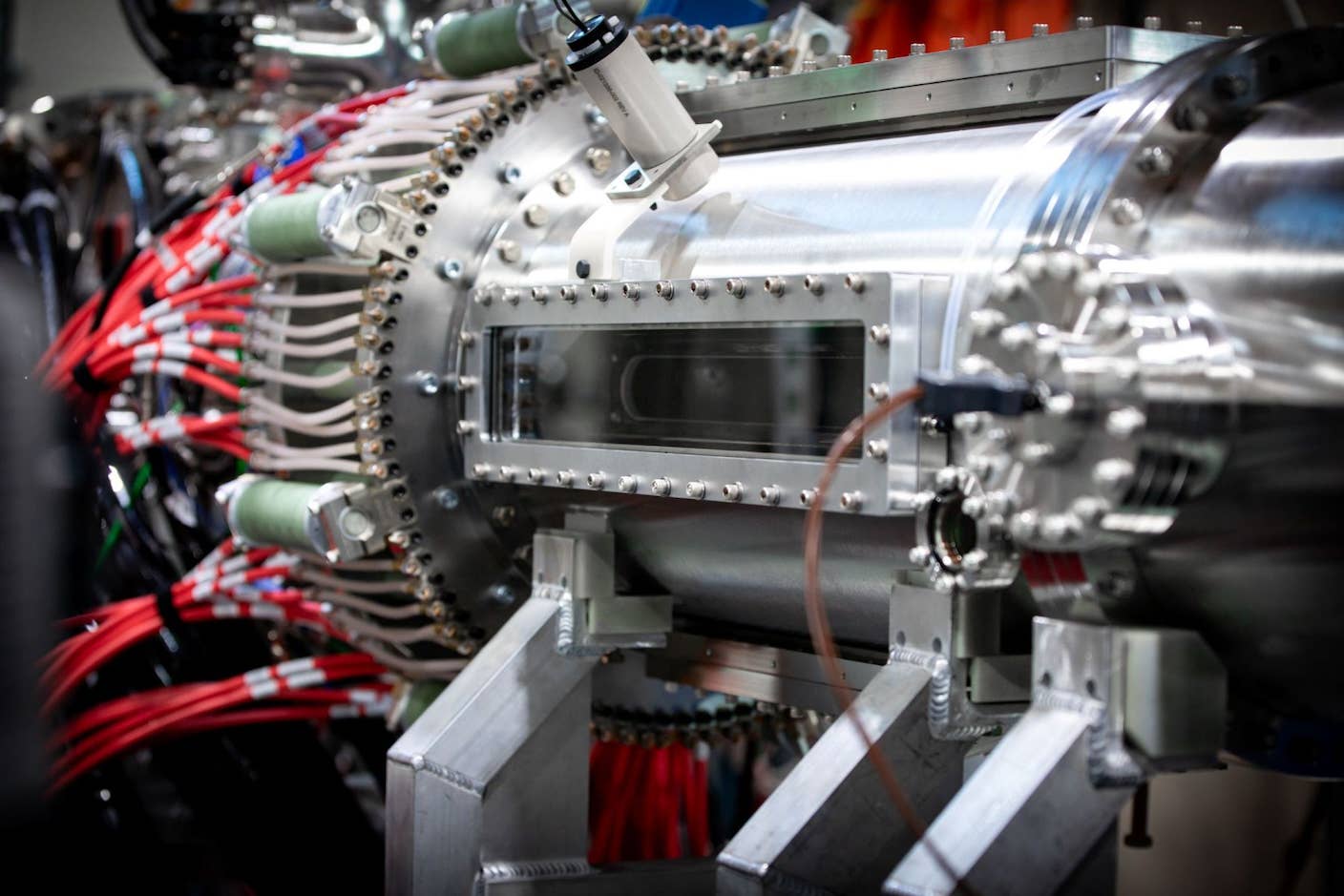

Image Credit: Shutterstock.com

Marc is British, Danish, Geekish, Bookish, Sportish, and loves anything in the world that goes 'booiingg'. He is a freelance journalist and researcher living in Tokyo and writes about all things science and tech. Follow Marc on Twitter (@wokattack1).

Related Articles

Startup Zap Energy Just Set a Fusion Power Record With Its Latest Reactor

Scientists Say New Air Filter Transforms Any Building Into a Carbon-Capture Machine

Investors Have Poured Nearly $10 Billion Into Fusion Power. Will Their Bet Pay Off?

What we’re reading