All the Brain-Boosting Goodness of Exercise…in a Pill?

Share

Lets face it: Love it or hate it, exercise is good for our brains.

Feeling stressed? Hit the trails: running boosts the fight-or-flight brain chemical norepinephrine and enhances our body’s ability to respond to stress. Got the winter blues? Working out just 30 minutes a day, a few times a week immediately ups overall mood and may combat depression. Can’t think straight? 20 minutes of lifting enhances long-term memory by about 10% in healthy young adults. Getting forgetful? Distance running increases brain volume, augments the birth of new neurons and slows age-related brain deterioration, even in old age.

The evidence is overwhelming: regular exercise may be as close to a brain-boosting elixir as we can get (plus it’s free!).

There’s just one problem: many of us don’t like to exercise. Some people — due to chronic illnesses such as cancer or other conditions — physically can’t. Yet these people often stand to gain the most from the mental benefits of working out.

The solution seems obvious. What if there’s a way to distill the positive effects of exercise, put it into a glorious pill and let everyone reap its mental benefits?

Muscle power

Yes, an “exercise pill” sounds like old news — but in truth, the quest is just getting started.

Late last year, a collaboration between the University of Sydney and the University of Copenhagen collected muscle tissue from four men who biked intensely for 10 minutes, and found over 1,000 different molecular changes.

“We’ve created an exercise blueprint that lays the foundation for future treatments, and the end goal is to mimic the effects of exercise,” said Dr. Nolan Hoffman, one of the authors of the study.

There’s more in the works. Recently the National Institute of Health organized a huge multi-center clinical study to try to map out, in unprecedented detail, how exercise changes our genes, protein turnover, metabolism and epigenetics — that is, how genes are expressed — in muscles and fatty tissue.

“Identification of the mechanisms that underlie the link between physical activity and improved health holds extraordinary promise for discovery of novel therapeutic targets and development of personalized exercise medicine,” wrote the participating researchers in a report in Cell Metabolism.

With the help of bioinformatics and big data, the search has been fruitful: a team from Harvard announced a drug that converts your stubborn white fat to the metabolically active brown fat, transforming fat-storing cells into thermogenic fuel-torching engines; a molecule dubbed “compound 14” tricks your body into thinking it’s low on energy, thereby pushing the cells’ energy factories into overdrive in an attempt to make more.

When we look at benefiting the brain, however, our cornucopia of potential exercise pills rapidly dwindles. None of the candidates discovered so far can make us sleep, feel and think better in the way that exercise can.

Scientists are just starting to bridge the gap. One crucial question stands in the way: exercise directly acts on the body’s skeletal muscle and cardiovascular system. So how does the brain know that the body just worked out?

The mythical messenger

What are the molecules that signal from the body to the brain after exercise?

It’s a question that’s already spurred one startup, caught the eye of leading venture capitalists and is potentially worth tens of millions of dollars.

It’s also one mired in controversy since the get-go.

In 2012, Dr. Bruce Spiegelman at Harvard Medical School announced the discovery of irisin, the bombshell “exercise mimetic” that thrilled the world. Named after the Greek messenger goddess Iris, irisin is a protein released by skeletal muscle after moderate running.

Irisin travels through the blood into the brain, where it stimulates brain cells to produce a nurturing protein called BDNF. BDNF is like mother’s milk for the brain: it coaxes the hippocampus — a brain region crucially involved in memory — to give birth to new neurons and adds to the brain’s computational powers. It also rebuilds worn-down structures within a neuron, and makes the brain more resilient to stressors that would usually cause cell death.

BDNF makes the brain bloom, and Irisin seems to be the harbinger.

Spiegelman’s work was almost immediately scrutinized by the scientific community. Anonymous comments flooded PubPeer, a popular forum where scientists discuss published papers, questioning the validity of the data and even the existence of the protein.

Three years later, Spiegelman and his team shot back at the naysayers with a new study that quantified the levels of irisin in the bloodstream of human volunteers — confirming that it’s real — and showed that it is, in fact, released after exercise.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Irisin’s rollercoaster to fame (or notoriety) isn’t just a nerd fight.

For one, it shows how tough it is to pinpoint messengers that bridge the blood and brain. For another, “exercise pill” has somewhat of the same negative connotations as “anti-aging pills.” Many scientists believe that exercise acts on the body and brain in too many ways, making the quest for a single pill nothing more than a fool’s errand. Others think “magical fat loss pills” have no place in respectable research.

But the potential impact of a true brain-boosting exercise pill is too strong to ignore. Amidst all the controversy, several pioneering teams are chipping away at the question.

One of the hottest new candidates is kynurenic acid, a muscle metabolite that protects the brain from stress-induced changes associated with depression, at least in mice.

Another is AICAR. Initially developed to protect the heart from injuries during surgery, AICAR boosts the expression of genes involved in oxygen metabolism and running endurance in mice. When used in old mice, it made them smarter and more agile.

Other examples include experimental drugs with somewhat unimaginative names, such as GW1516. These act locally on muscles but also affect the mind: mice taking GW1516 for a week performed much better on tests for learning and memory. When scientists peeked into their brains, they found abundant new neurons scattered all across the hippocampus.

Pills for treadmills?

Most of the research so far was done in mice. But the results are likely to work in humans as well — if you’re willing to bear side effects such as gout, heart valve defects and reduced blood flow to the brain and heart.

The side effects of most of these drug candidates are still unclear, but the temptation of a better body and brain is strong. Since 2013, a few drug candidates have made the (underground) leap into humans — specifically, endurance athletes. Cases of professional cyclists doping GW1516 were so frequent that it prompted the World Anti-Doping Agency to issue a warning against the drug.

For the rest of us, a safe and effective exercise pill is still a ways off. At the moment, scientists are still trying to figure out what kind of exercise — distance running, high-intensity interval training or weight training — benefits the brain the most (spoiler: running gets the gold).

"We are at the early stages of this exciting new field," said Dr. Ismail Laher. a scientist at the University of British Columbia who recently published a think piece on the future of exercise pills.

“These medications have life-changing potential for some people,” agreed bioethicist Dr. Arthur Caplan at the NYU School of Medicine. But he warns against unintended consequences.

“If you install seat belts and airbags in cars people drive faster,” he said. “I just think (exercise pills) should be introduced gradually so that populations who really can’t exercise might see the benefits while harm to the general population can be minimized.”

It’s a field that’s rapidly moving forward, and well worth keeping tabs on. And maybe someday we’ll have an exercise-mimicking pill that, in terms of health, transforms couch potatoes into elite athletes.

But until then, for a natural body and brain-boost, hit the treadmill.

Image credit: Shutterstock.com

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

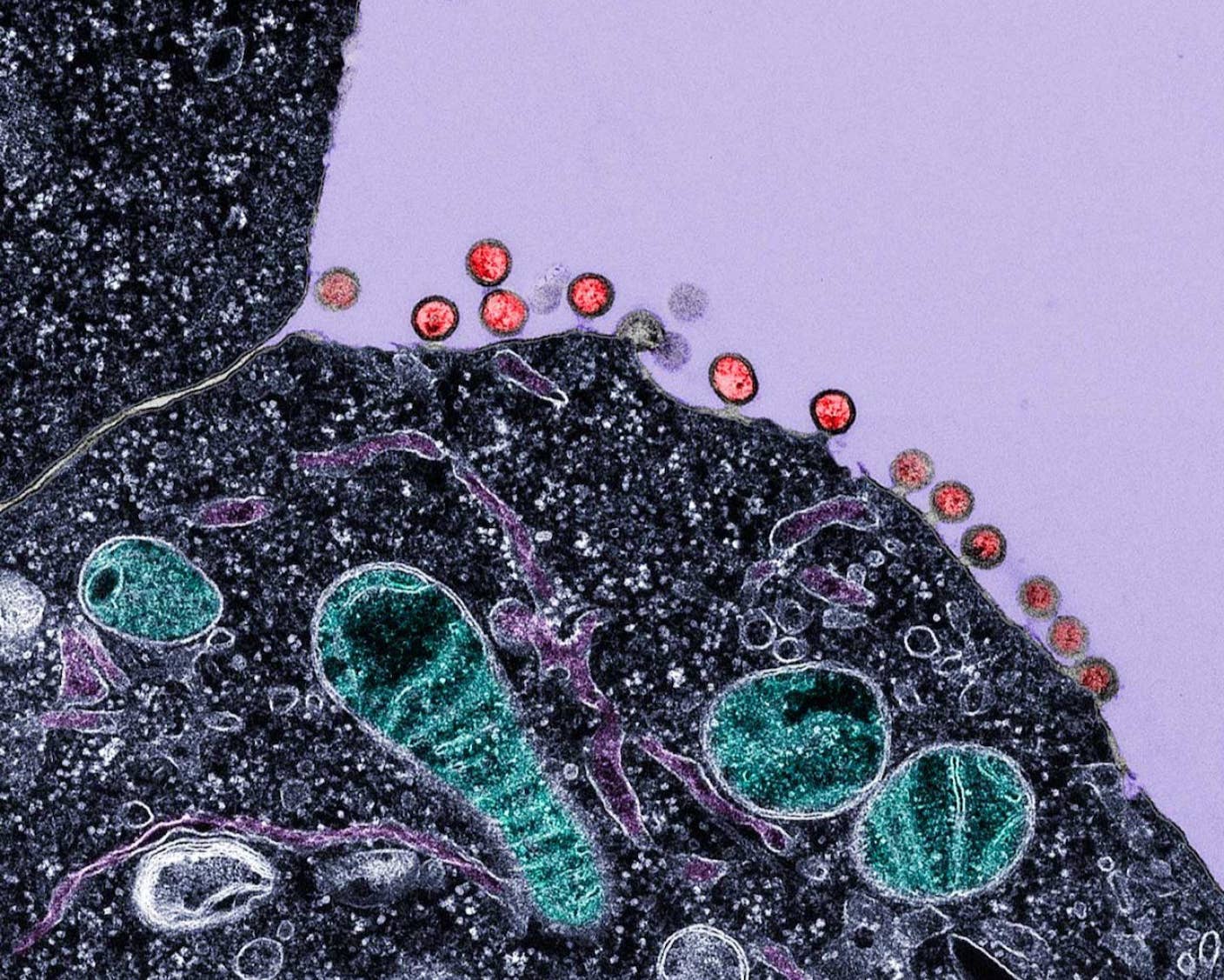

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

Scientists Just Developed a Lasting Vaccine to Prevent Deadly Allergic Reactions

One Dose of This Gene Editor Could Defeat a Host of Genetic Diseases Suffered by Millions

What we’re reading