Risk Takers Are Back in the Space Race—and That’s a Good Thing

Share

“In a fight between Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, who would win?” Peter Diamandis asked Blue Origin’s Erika Wagner to kick off a conversation with a panel of space entrepreneurs at Singularity University’s Global Summit this week in San Francisco.

“So, Peter, let me tell you about what we’re doing at Blue Origin,” Wagner answered rather diplomatically, eliciting chuckles from the audience. “We're really looking towards a future of millions of people living and working in space. The thing I think is really fantastic…is that the universe is infinitely large, and so, we don’t need any fisticuffs."

“We’re all going to go out there and create this future together.”

Diamandis is no stranger to the private space race. He’s long been a passionate investor in and driver of the new space industry. The first private suborbital flight in 2004—incented by his $10 million Ansari XPRIZE competition—hinted at how much could be built outside of government space agencies. But really, only the last few years have begun to deliver on the promise.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is the best-known new space firm. But 15 years ago, SpaceX didn’t exist. Seven years ago, they’d never launched a vehicle. Five years ago, they’d yet to resupply the International Space Station. And two years ago, there was no such thing as a reusable rocket.

Now, the company is routinely delivering satellites to orbit, resupplying the ISS, and recovering the first stages of their rockets. But they aren’t alone. In fact, Jeff Bezos’s Blue Origin recovered a suborbital New Shepard rocket before SpaceX successfully landed their orbital Falcon 9. And Blue Origin aims to go beyond suborbital flight with the upcoming New Glenn rocket.

So, no zero-g fisticuffs yet, but plenty of competition. Which is a good thing. Making space a more affordable place to visit will open other opportunities when we get there.

Planetary Resources, a company Diamandis cofounded, has plans to expand the global economy into space by prospecting and mining asteroids. And another space mining startup and Google Lunar XPRIZE finalist, Moon Express, aims to mine the moon for the same reasons.

Chris Lewicki, CEO of Planetary Resources, and Bob Richards, cofounder and CEO of Moon Express, joined Diamandis and Wagner on stage to talk over the trends making this possible.

Left to right: Peter Diamandis, Chris Lewicki, Erika Wagner, and Bob Richards at Singularity University's Global Summit in San Francisco.

The panel said exponential technologies—such as 3D printing, computing, and robotics—are a big reason feats that were once the sole domain of a few governments are becoming possible for startups with a team of 50 or 100 talented workers.

“We always talk about space being a place where spin-offs happen, where we would go spend a lot of money on Apollo and, in exchange, we get Teflon and cordless drills,” Wagner said. “And it turns out, now we're back in a part of the cycle where space is where spin-ins are happening.”

Perhaps this is most obvious in the size of satellites. Not too long ago, most satellites had to be the size of a house to include whatever instruments they carried. These days, in some cases, similar capabilities can be shipped to space in a box 10 centimeters to the side.

“Very similar to what happened in the computation world from the mainframe era of computers, things that were government-centric and filled a room were transformed into personals PCs…That’s what’s happening in space,” according to Richards.

Perhaps less obvious but no less important is the actual computation working under the hood.

SpaceX’s reusable rockets aren’t manually steered into a soft landing by remote pilots back at mission control. No human is capable of that task. Instead, computers take in a flood of information from onboard sensors and make rapid and continuous adjustments to land.

They’re basically self-driving rockets. The same technologies making autonomous cars possible are involved here too. And there might even be feedback between the two—much of the work done in space, after all, will continue to be done by robot. And in space, where communications can be sketchy and delayed, the more autonomous the better.

“I look at every autonomous car startup out there and think about where they will be in 5 to 10 years,” Lewicki said. “[I think about] all the sensors and all the technology that they will have commoditized that will make asteroid mining quite easy.”

Additive manufacturing has likewise found a niche in aerospace. 3D printers speed up the design-and-test process and also yield finished parts you can’t make any other way.

“[Blue Origin’s] New Shepard rocket has literally hundreds of 3D printed parts,” Wagner said. “It started off as the brackets and the guides and little pieces, and now, they're increasingly moving into the hot end of the engine and really are part and parcel to how our rockets work.”

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

All this, according to the panel, is reducing the time and cost of space projects.

“Our first quotes from an unnamed large aerospace company for our propulsion system in 2010 was $24 million in 24 months. We're now printing our engines for $2,000 in two weeks,” Richards said.

The economics matter. Although significant seed money is being put up by billionaires like Musk and Bezos, they won’t be able to foot the whole bill forever. Such investments need to show practical value too if the area is going to take off.

This, perhaps, is the most interesting bit of it all.

According to Richards, you don’t “get giggled at anymore” when proposing a space startup. Beyond individuals, strategic corporate partnerships and even sovereign wealth funds are emerging sources of funding. And venture capital firms are interested too.

The opportunity is enormous, according to Diamandis.

"Everything we hold of value on Earth: metals, minerals, energy, real estate, are in near infinite quantities in space," he said. "And so I've said this many times, I believe the first trillionaires will be made in space and the resources that we're talking about are multitrillion dollar assets."

While space startups aren’t giggled at anymore, however, neither are they fully mainstream. SpaceX is leading the way, but there hasn’t been what the panel called “a Netscape moment” yet, referring to the first big web browser that opened the internet for business. The new space industry isn’t yet irresistible in the same way.

SpaceX is making its reusable rockets look routine, and has lost a few along the way too. Virgin Galactic, the company Richard Branson founded with the ship developed for the original XPRIZE, lost a pilot in a tragic crash over the Mojave Desert a few years ago. There are still many risks and challenges, big visions and ambitions and unforeseen delays.

But if risk is necessary to move forward, the commercial environment is a better place to experiment, take risks, and try new things, according to Lewicki. There’s a reason, he said, that NASA’s next Mars rover will use processors built in 1993. They work. They’ll get the job done. The rover will roll across Mars. But it is nowhere near as capable as it could be.

“It's a failure-is-not-an-option mentality,” Lewicki said. “And when failure's not an option, success gets really expensive, and you worry about risk everywhere.”

For a startup, on the other hand, the risk-averse approach is not an option. They have to draw up a grand vision of something that isn't yet here and push the envelope to make it happen. Whatever the outcome, they all agreed, this is a special moment.

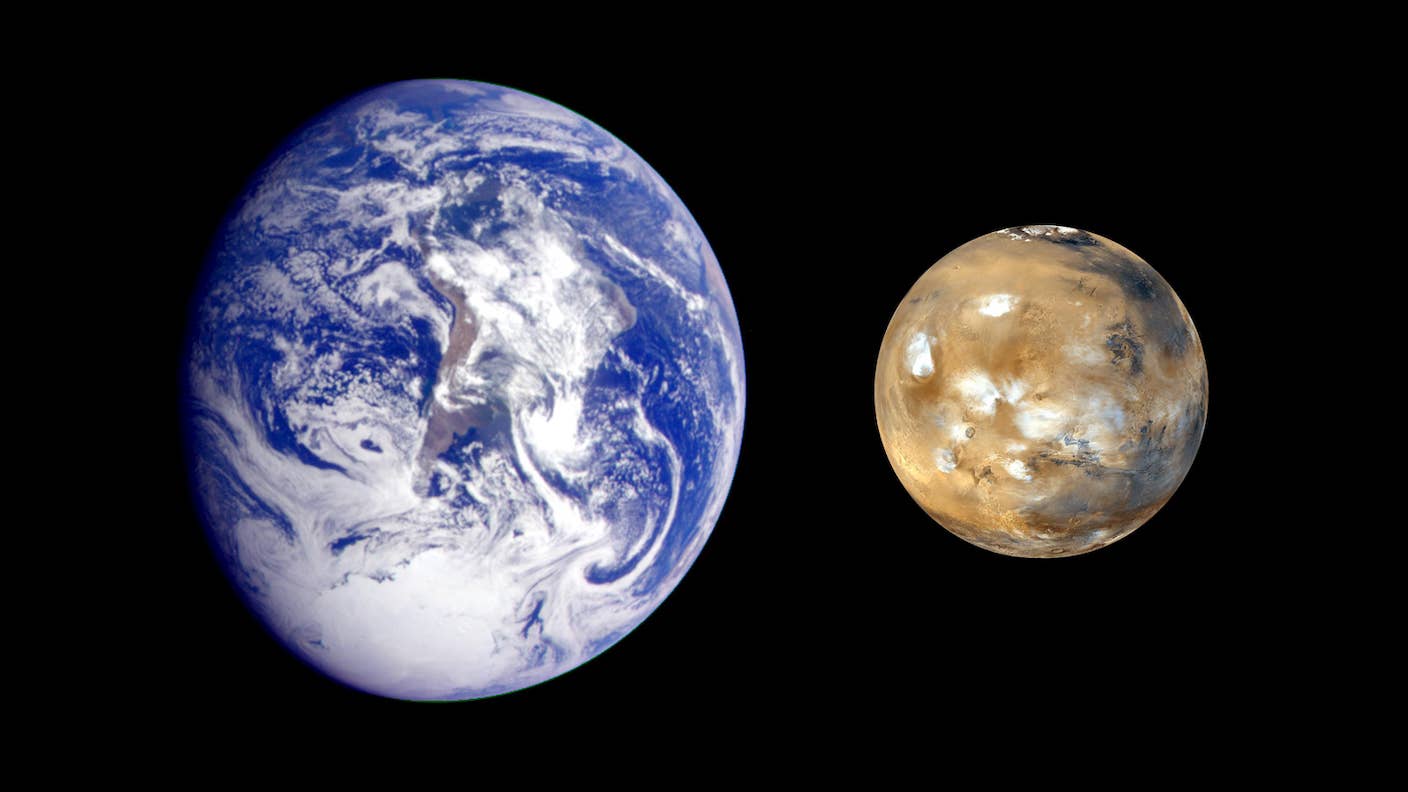

"Thousands of years from now whatever we evolve into, whatever we become, we're going to look back at these next couple of decades as the moment in time that the human race moved off the planet irreversibly," Diamandis said. "It's on our watch. It's right here, right now that we're becoming a multiplanetary species, which is an extraordinary thought."

Image Credit: Blue Origin

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

What we’re reading