Dinosaurs Could Have Avoided Mass Extinction If the Killer Asteroid Had Landed Almost Anywhere Else

Share

The decline of the dinosaurs, the rise of mammals and, ultimately, the origins of humans were even more unlikely than previously thought, according to new research. The huge asteroid collision that sparked this change in the Earth’s diversity was already a highly improbable roll of the celestial dice. But a new study suggests the mass extinction that followed it was only so severe because of where the asteroid struck.

Scientists believe the dinosaurs were largely wiped out 66 million years ago when an asteroid collision released a huge dust and soot cloud that triggered global climate change. The researchers, from Tohoku University in Japan, claim that the soot necessary for such a global catastrophe could only have come from a direct impact on rocks especially rich in hydrocarbons.

Rocks like this would only have been found on about 13% of the Earth’s surface. Add to this the need for a liberal dose of toxic sulfurous compounds in the rocks, and the odds that an impact of the same size (an already astronomically rare event) would have such devastating consequences lengthen to just one in 100.

The impact crater created by the 10-kilometer-diameter asteroid is located close to Chicxulub on Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula and was only identified as recently as 1991. Before then, it was hidden to scientists because it lay partly under a blanket of sediment on the seabed.

The underlying rocks were composed of gypsum (rich in sulfur) and also contained large reserves of hydrocarbons. Had the impact occurred a few hundred miles away, or indeed at most locations on the globe, then the consequences of the collision may have been vastly less severe. Terrestrial dinosaurs and many other groups may never have been driven to extinction, and their survival may have hindered or completely prevented the later spread of mammals—and, of course, humans.

Global blackout. Image Credit: Herschel Hoffmeyer / Shutterstock.com

The immediate blast and resulting shock and tidal waves would have killed much in their path no matter where the impact had occurred. Earthquakes and volcanic activity would have been triggered worldwide, and pieces of burning debris may have started extensive wildfires.

But it’s unlikely this would have caused the global extinction of huge numbers of species. Such immediate effects were relatively short-lived, and the real damage, as the researchers show, probably came from fine particulate matter ejected high into the stratosphere. The worst culprit, they argue, would have been fine hydrocarbon soots. This new research claims that those catapulted into the upper atmosphere probably originated from rocks at the impact site rather than from forest fires.

Soot in the stratosphere could have simply blocked out the sun over a period of years, creating the equivalent of a nuclear winter, shutting down photosynthesis and decimating ecosystems as a result. But the researchers argue that as well as general darkening, the effects upon climate were more varied, resulting in droughts towards the equator and more extreme cooling at mid to high latitudes. Sulfate aerosols would also have caused acid rain, altering ocean chemistry and stressing marine and terrestrial ecosystems alike.

The Tohoku scientists used global climate models to predict the size of these effects depending upon the geology of where the asteroid struck, as well as the volume and chemistry of the material thrown into the upper atmosphere. In most other locations, it wouldn’t have produced such devastating results. It seems that the Earth could not have been hit anywhere much worse.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The next mass extinction

All species inevitably go extinct and the history of life on Earth is one of constant turnover. Extinctions also occur at all scales, from the demise of individual species to what we call “mass events” that see 75% or more of species wiped out globally. There have been five such mass events over the last half billion years, and we appear to be sleepwalking into a sixth of our own making thanks to pollution, habitat destruction, and hunting.

The possibility of a future asteroid impact is also very real. NASA’s Near Earth Object Program seeks to map out the trajectories of comets and asteroids that appear set to come close to the Earth. Plans are afoot to develop technologies capable of deflecting objects on a collision course.

But in the meantime, this new research suggests that we should worry slightly less about the probable consequences of the next extraterrestrial disaster, focus our attention closer to home, and reflect on our outrageous good fortune for being here in the first place.

Matthew Wills, Professor of Evolutionary Palaeobiology at the Milner Centre for Evolution, University of Bath

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

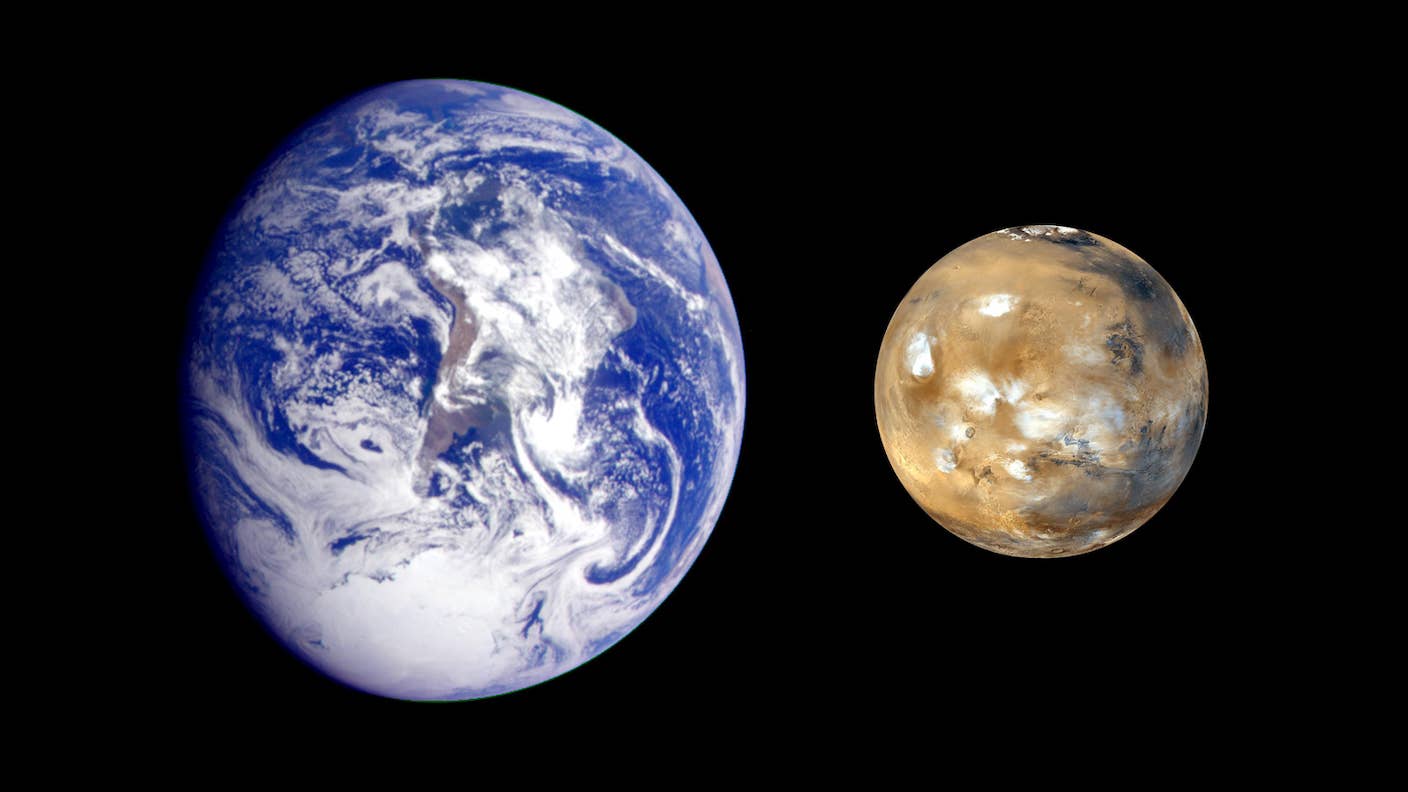

Image Credit: muratart / Shutterstock.com

Professor Matthew Wills was a student and postdoc in Bristol, spent a year working with Doug Erwin at the Smithsonian, and was for two years an Assistant Curator at the Oxford University Museum. He moved to Bath in 2000, where he is now part of the Milner Centre for Evolution. His interests include macroevolutionary patterns and trends, particularly the manner in which groups rapidly explore their morphological ‘design’ options. He still hasn’t got the hang of Thursdays.

Related Articles

More Space Junk Is Plummeting to Earth. Earthquake Sensors Can Track It by the Sonic Booms.

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

What we’re reading