How a Machine That Can Make Anything Would Change Everything

Share

“Something is going to happen in the next forty years that will change things, probably more than anything else since we left the caves.” –James Burke

James Burke has a vision for the future. He believes that by the middle of this century, perhaps as early as 2042, our world will be defined by a new device: the nanofabricator.

These tiny factories will be large at first, like early computers, but soon enough you’ll be able to buy one that can fit on a desk. You’ll pour in some raw materials—perhaps water, air, dirt, and a few powders of rare elements if required—and the nanofabricator will go to work. Powered by flexible photovoltaic panels that coat your house, it will tear apart the molecules of the raw materials, manipulating them on the atomic level to create…anything you like. Food. A new laptop. A copy of Kate Bush’s debut album, The Kick Inside. Anything, providing you can give it both the raw materials and the blueprint for creation.

It sounds like science fiction—although, with the advent of 3D printers in recent years, less so than it used to. Burke, who hosted the BBC show Tomorrow’s World, which introduced bemused and excited audiences to all kinds of technologies, has a decades-long track record of technological predictions. He isn’t alone in envisioning the nanofactory as the technology that will change the world forever. Eric Drexler, thought by many to be the father of nanotechnology, wrote in the 1990s about molecular assemblers, hypothetical machines capable of manipulating matter and constructing molecules on the nano level, with scales of a billionth of a meter.

Richard Feynman, the famous inspirational physicist and bongo-playing eccentric, gave the lecture that inspired Drexler as early as 1959. Feynman's talk, "Plenty of Room at the Bottom," speculated about a world where moving individual atoms would be possible. While this is considered more difficult than molecular manufacturing, which seeks to manipulate slightly bigger chunks of matter, to date no one has been able to demonstrate that such machines violate the laws of physics.

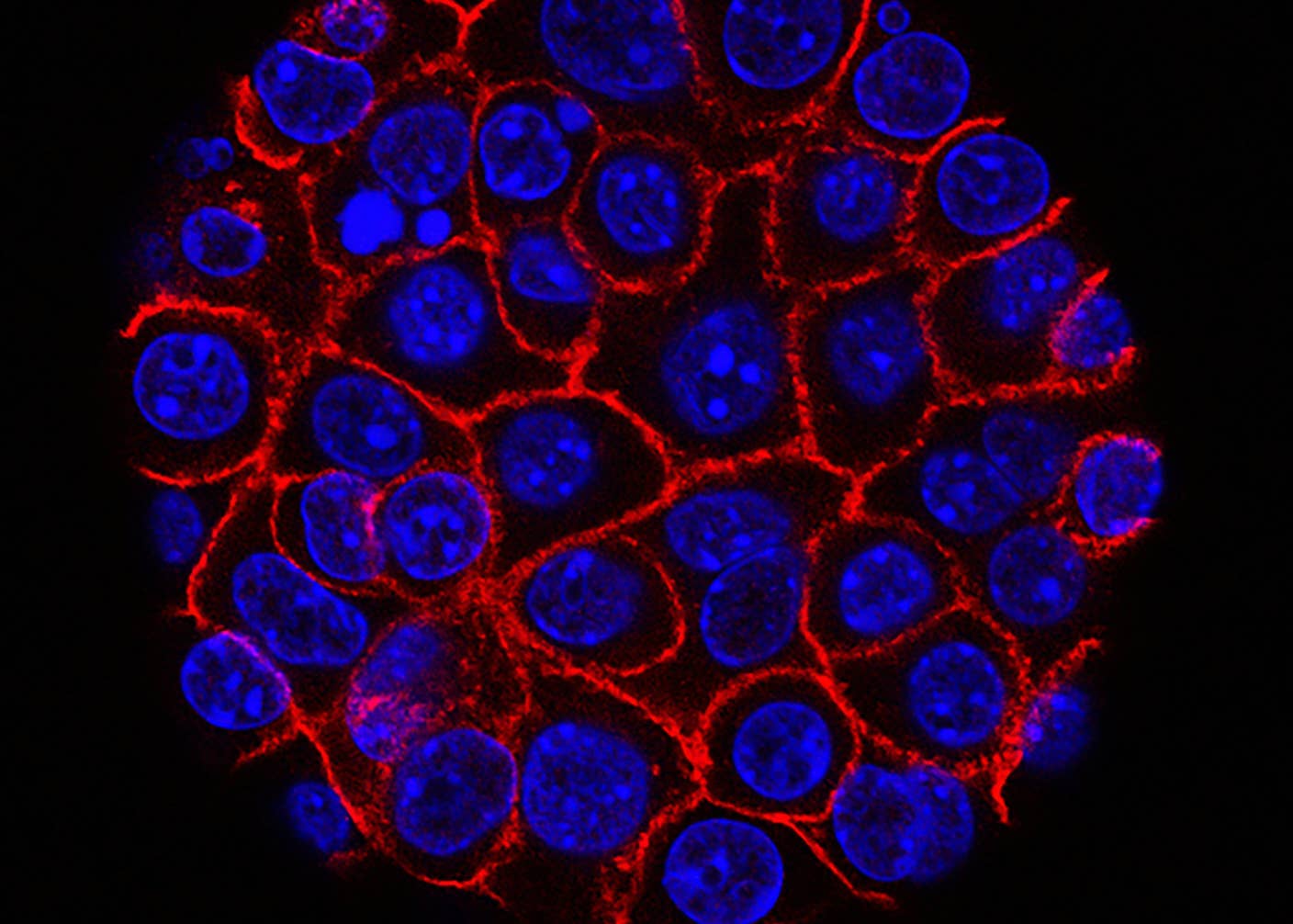

In recent years, progress has been made towards this goal. It may well be that we make faster progress by mimicking the processes of biology, where individual cells, optimized by billions of years of evolution, routinely manipulate chemicals and molecules to keep us alive.

"If nanofabricators are ever built, the systems and structure of the world as we know them were built to solve a problem that will no longer exist."

But the dream of the nanofabricator is not yet dead. What is perhaps even more astonishing than the idea of having such a device—something that could create anything you want—is the potential consequences it could have for society. Suddenly, all you need is light and raw materials. Starvation ceases to be a problem. After all, what is food? Carbon, hydrogen, nitrogen, phosphorous, sulphur. Nothing that you won’t find with some dirt, some air, and maybe a little biomass thrown in for efficiency’s sake.

Equally, there’s no need to worry about not having medicine as long as you have the recipe and a nanofabricator. After all, the same elements I listed above could just as easily make insulin, paracetamol, and presumably the superior drugs of the future, too.

What the internet did for information—allowing it to be shared, transmitted, and replicated with ease, instantaneously—the nanofabricator would do for physical objects. Energy will be in plentiful supply from the sun; your Santa Clause machine will be able to create new solar panels and batteries to harness and store this energy whenever it needs to.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Suddenly only three commodities have any value: the raw materials for the nanofabricator (many of which, depending on what you want to make, will be plentiful just from the world around you); the nanofabricators themselves (unless, of course, they can self-replicate, in which case they become just a simple ‘conversion’ away from raw materials); and, finally, the blueprints for the things you want to make.

In a world where material possessions are abundant for everyone, will anyone see any necessity in hoarding these blueprints? Far better for a few designers to tinker and create new things for the joy of it, and share them with all. What does ‘profit’ mean in a world where you can generate anything you want?

As Burke puts it, “This will destroy the current social, economic, and political system, because it will become pointless…every institution, every value system, every aspect of our lives have been governed by scarcity: the problem of distributing a finite amount of stuff. There will be no need for any of the social institutions.”

In other words, if nanofabricators are ever built, the systems and structure of the world as we know them were built to solve a problem that will no longer exist.

In some ways, speculating about such a world that’s so far removed from our own reminds me of Eliezer Yudkowsky’s warning about trying to divine what a superintelligent AI might make of the human race. We are limited to considering things in our own terms; we might think of a mouse as low on the scale of intelligence, and Einstein as the high end. But superintelligence breaks the scale; there is no sense in comparing it to anything we know, because it is different in kind. In the same way, such a world would be different in kind to the one we live in today.

We, too, will be different in kind. Liberated more than ever before from the drive for survival, the great struggle of humanity. No human attempts at measurement can comprehend what is inside a black hole, a physical singularity. Similarly, inside the veil of this technological singularity, no human attempts at prognostication can really comprehend what the future will look like. The one thing that seems certain is that human history will be forever divided in two. We may well be living in the Dark Age before this great dawn. Or it may never happen. But James Burke, just as he did over forty years ago, has faith.

Image Credit: 3DSculptor / Shutterstock.com

Thomas Hornigold is a physics student at the University of Oxford. When he's not geeking out about the Universe, he hosts a podcast, Physical Attraction, which explains physics - one chat-up line at a time.

Related Articles

These Supercharged Immune Cells Completely Eliminated Solid Tumors in Mice

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

This Week’s Awesome Tech Stories From Around the Web (Through February 28)

What we’re reading