6G Will Be 100 Times Faster Than 5G—and Now There’s a Chip for It

Share

Though 5G—a next-generation speed upgrade to wireless networks—is scarcely up and running (and still nonexistent in many places) researchers are already working on what comes next. It lacks an official name, but they’re calling it 6G for the sake of simplicity (and hey, it’s tradition). 6G promises to be up to 100 times faster than 5G—fast enough to download 142 hours of Netflix in a second—but researchers are still trying to figure out exactly how to make such ultra-speedy connections happen.

A new chip, described in a paper in Nature Photonics by a team from Osaka University and Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, may give us a glimpse of our 6G future. The team was able to transmit data at a rate of 11 gigabits per second, topping 5G’s theoretical maximum speed of 10 gigabits per second and fast enough to stream 4K high-def video in real time. They believe the technology has room to grow, and with more development, might hit those blistering 6G speeds.

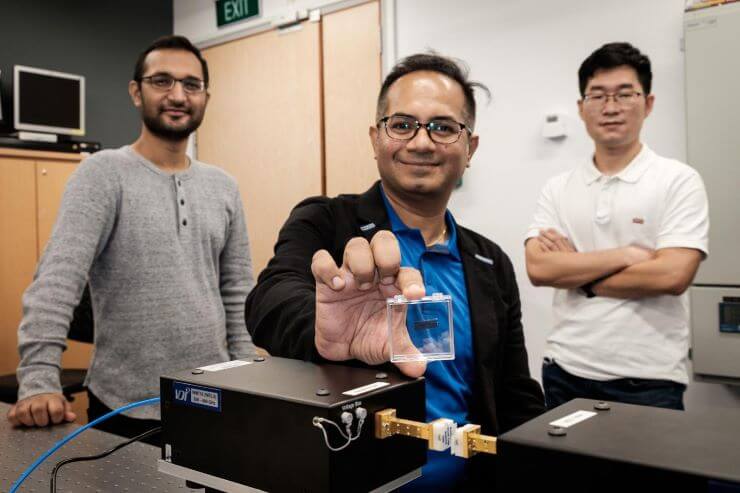

NTU final year PhD student Abhishek Kumar, Assoc Prof Ranjan Singh and postdoc Dr Yihao Yang. Dr Singh is holding the photonic topological insulator chip made from silicon, which can transmit terahertz waves at ultrahigh speeds. Credit: NTU Singapore

But first, some details about 5G and its predecessors so we can differentiate them from 6G.

Electromagnetic waves are characterized by a wavelength and a frequency; the wavelength is the distance a cycle of the wave covers (peak to peak or trough to trough, for example), and the frequency is the number of waves that pass a given point in one second. Cellphones use miniature radios to pick up electromagnetic signals and convert those signals into the sights and sounds on your phone.

4G wireless networks run on millimeter waves on the low- and mid-band spectrum, defined as a frequency of a little less (low-band) and a little more (mid-band) than one gigahertz (or one billion cycles per second). 5G kicked that up several notches by adding even higher frequency millimeter waves of up to 300 gigahertz, or 300 billion cycles per second. Data transmitted at those higher frequencies tends to be information-dense—like video—because they’re much faster.

The 6G chip kicks 5G up several more notches. It can transmit waves at more than three times the frequency of 5G: one terahertz, or a trillion cycles per second. The team says this yields a data rate of 11 gigabits per second. While that’s faster than the fastest 5G will get, it’s only the beginning for 6G. One wireless communications expert even estimates 6G networks could handle rates up to 8,000 gigabits per second; they’ll also have much lower latency and higher bandwidth than 5G.

Terahertz waves fall between infrared waves and microwaves on the electromagnetic spectrum. Generating and transmitting them is difficult and expensive, requiring special lasers, and even then the frequency range is limited. The team used a new material to transmit terahertz waves, called photonic topological insulators (PTIs). PTIs can conduct light waves on their surface and edges rather than having them run through the material, and allow light to be redirected around corners without disturbing its flow.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

The chip is made completely of silicon and has rows of triangular holes. The team’s research showed the chip was able to transmit terahertz waves error-free.

Nanyang Technological University associate professor Ranjan Singh, who led the project, said, "Terahertz technology [...] can potentially boost intra-chip and inter-chip communication to support artificial intelligence and cloud-based technologies, such as interconnected self-driving cars, which will need to transmit data quickly to other nearby cars and infrastructure to navigate better and also to avoid accidents."

Besides being used for AI and self-driving cars (and, of course, downloading hundreds of hours of video in seconds), 6G would also make a big difference for data centers, IoT devices, and long-range communications, among other applications.

Given that 5G networks are still in the process of being set up, though, 6G won’t be coming on the scene anytime soon; a recent whitepaper on 6G from Japanese company NTTDoCoMo estimates we’ll see it in 2030, pointing out that wireless connection tech generations have thus far been spaced about 10 years apart; we got 3G in the early 2000s, 4G in 2010, and 5G in 2020.

In the meantime, as 6G continues to develop, we’re still looking forward to the widespread adoption of 5G.

Image Credit: Hans Braxmeier from Pixabay

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

AI Companies Are Betting Billions on AI Scaling Laws. Will Their Wager Pay Off?

Super Precise 3D Printer Uses a Mosquito’s Needle-Like Mouth as a Nozzle

Is the AI Bubble About to Burst? What to Watch for as the Markets Wobble

What we’re reading