Autonomous Ravn X Drone to Launch Satellites From Airport Runways

Share

Huntsville Alabama’s Lowe Mill arts and entertainment center offers studios to artists of all kinds—sculptors, bookbinders, woodworkers. It’s the kind of place where, in more normal times, visitors might wander open studios and take ceramics classes.

It’s also, evidently, the kind of place where one designs autonomous drones to launch rockets.

Lowe Mill, you see, is owned by angel investor, Jim Hudson, and the headquarters of one of Hudson’s investments occupies 7,000 square feet at the former textile mill. The startup, Aevum, just unveiled the product of years of work—a sleek rocket-launching aircraft called Ravn X.

Ravn X is 80 feet long, 18 feet tall, and has a 60-foot wingspan. Aevum claims it’s the world’s biggest autonomous aircraft (private or military). It has no cockpit because, obviously, it has no need of a pilot. Instead, after autonomously taking off from an average-length runway, Ravn X will lift a two-stage, liquid-fueled rocket as high as 60,000 feet. It will release its payload, the rocket’s first stage will fire, and from there, it’ll race into orbit.

That’s the plan at least. Ravn X is ready to fly, but has yet to take off.

Aevum was founded in 2016 by CEO Jay Skylus and focused early on design, software, and building rockets. By 2019, the company had made good progress but needed a contract to fund its first launch. That funding materialized late in the year, when another startup, Vector, filed for bankruptcy, and the US Space Force transferred a $4.9 million contract—the Agile Small Launch Operational Normalizer (ASLON-45)—to Aevum. The company will begin testing in 2021, and hopefully attempt a first launch, likely ASLON-45, from Florida's Cecil Spaceport within the year.

Founder and CEO Jay Skylus and Ravn X. Image Credit: Aevum

Ravn X is designed to minimize cost and make use of existing tech and infrastructure. The drone runs on standard jet fuel, can be operated from an airport, and should be as easily reusable as a commercial jet. The company also hopes to win customers with a more seamless experience. They'll coordinate logistics start to finish, including the likes of payload transport and integration, for a more plug-and-play experience for clients.

Put the pieces together and Aevum thinks Ravn X will offer speed (launches as fast as every 180 minutes), flexibility (flying around weather to avoid launch delays), and low risk and labor costs (a crew of six, no pilot).

All this will be key. The company is one of a number of space startups vying for a slice of the satellite market.

Everyone knows SpaceX, of course. But where SpaceX is poised to dominate large payloads, smaller rockets aim to deliver faster, cheaper launches in the small-sat niche. Small satellites are coming of age as miniature sensors, electronics, and computers endow capabilities once reserved for bus-sized satellites on satellites the size of a few toasters.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Rocket Lab is chief among small-sat providers. It's already proven its rockets and is delivering payloads to orbit. Rocket Lab is one of two US startups—SpaceX being the other—that's made orbit. There's also other competition that's a bit more like Ravn X (though no one else yet offers autonomous launch capabilities).

Northrop Grumman's Pegasus is the most established example. Pegasus is an air-launched rocket lifted by a Lockheed L-1011 (a widebody jet like a Boeing 747) that's been in operation since the 1990s. Pegasus differs in its use of solid rocket fuel. Solid rockets are less complex and more reliable, but also, potentially less safe. Once lit, there's no turning off a solid rocket (short of blowing it up). Liquid rockets can be shut down if needed.

Virgin Orbit sits somewhere between Pegasus and Aevum. The sister company to Virgin Galactic will air-launch liquid rockets from a Boeing-747. The company won a $35 million US Space Force contract for 44 small satellites over three launches, the first of which is scheduled for fall 2021.

But Virgin’s experience may be instructive when it comes to timelines.

The company had planned to begin testing and commercial launch as early as 2018, but testing began this year instead. In their first launch attempt, the rocket didn’t fire and had to be ditched in the ocean. This was not unexpected—it took SpaceX a few tries to get to orbit—and it yielded data, as intended, to dial in future tests. A subsequent planned attempt was recently scrubbed due to the pandemic.

Similarly, the startup that first won the ASLON-45 contract, Vector, had aimed for commercial operations in 2019 before its financial troubles. Aevum appears financially more stable, claiming $1 billion in government contracts, but there's always uncertainty and the possibility of unexpected delays in space exploration. Timelines are necessary but apt to change. As Popular Science writer Andrew Rosenblum put it in 2018: "This is literally rocket science, and the risks of fiery explosion, costly technical delays, and regulatory snafu are omnipresent."

Whether Aevum's Ravn X gets to space next year remains to be seen. Still, the company is yet another example of a private space industry—increasingly fueled by experimentation at speed—offering new ways to get people and stuff into orbit and beyond. From SpaceX to autonomous drone launches, it's an exciting time for those with their eyes on the next frontier.

Image Credit: Aevum

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

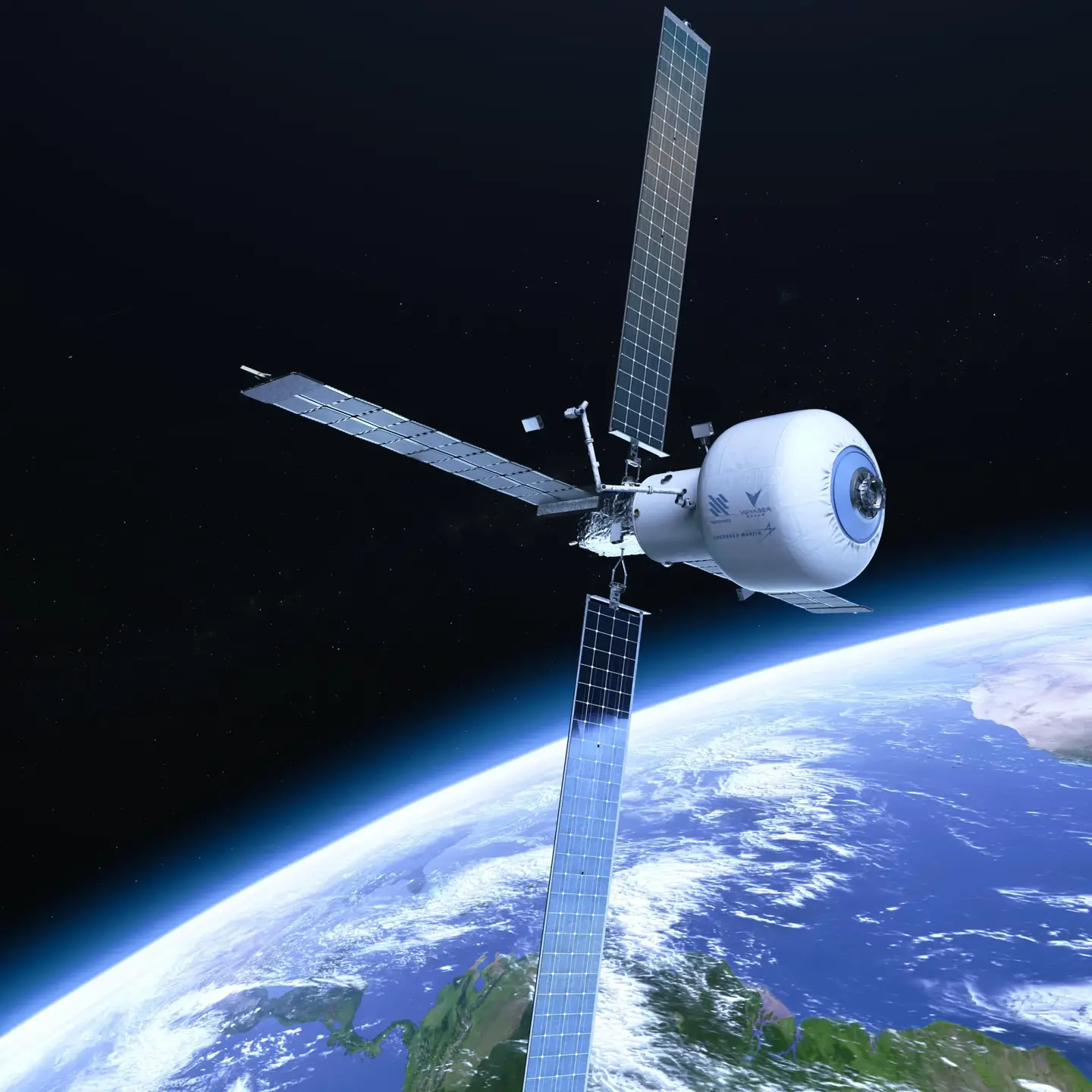

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading