How Many Galaxies Are in the Universe? A New Answer From the Darkest Sky Ever Observed

Share

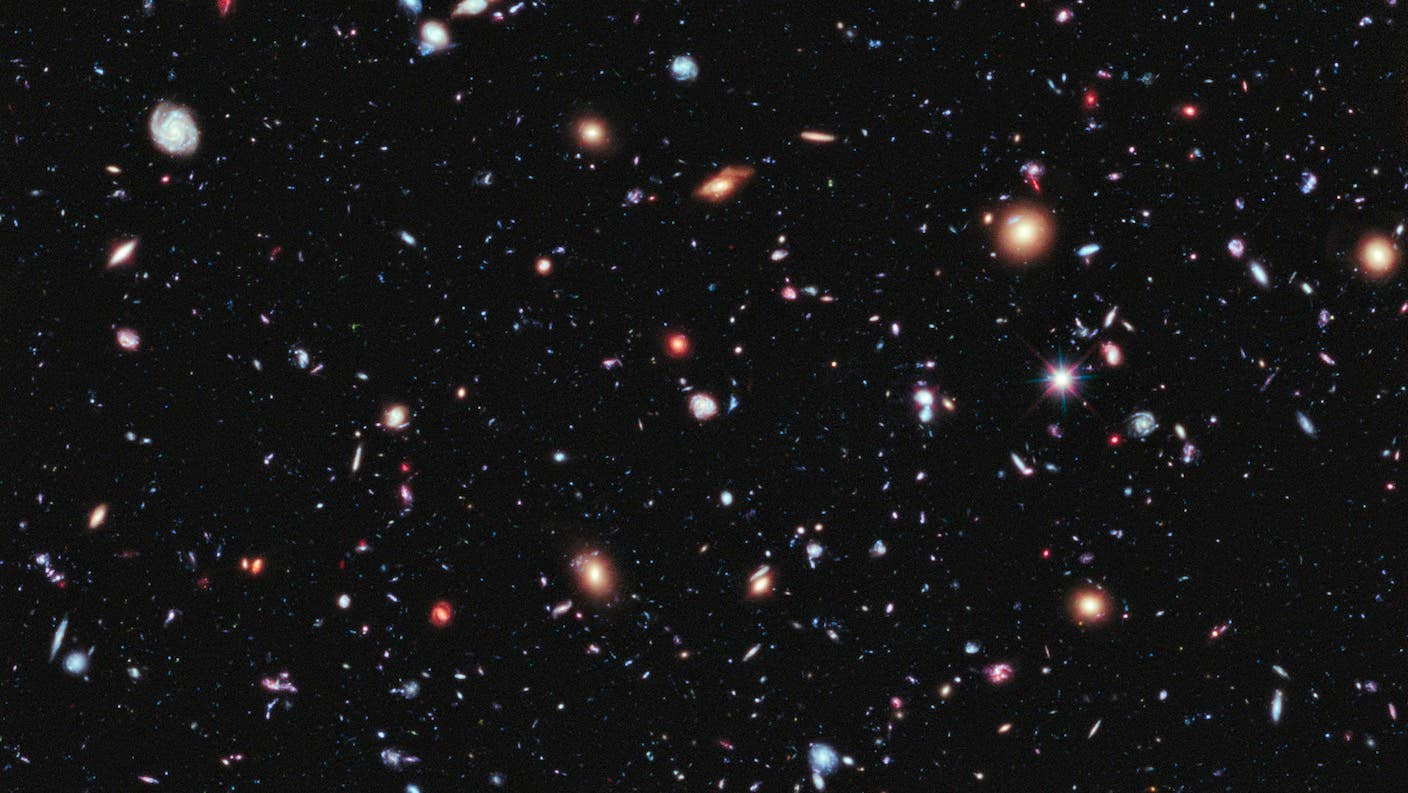

Ordinarily, we point telescopes at some object we want to see in greater detail. In the 1990s astronomers did the opposite. They pointed the most powerful telescope in history, the Hubble Space Telescope, at a dark patch of sky devoid of known stars, gas, or galaxies. But in that sliver of nothingness, Hubble revealed a breathtaking sight: The void was brimming with galaxies.

Astronomers have long wondered how many galaxies there are in the universe, but until Hubble, the galaxies we could observe were far outnumbered by fainter galaxies hidden by distance and time. The Hubble Deep Field series (scientists made two more such observations) offered a kind of core sample of the universe going back nearly to the Big Bang. This allowed astronomers to finally estimate the galactic population to be at least around 200 billion.

Why “at least”? Because even Hubble has its limits.

The further out (and back in time) you go, galaxies get harder to see. One cause of this is the pure distance the light must travel. A second reason is due to the expansion of the universe. The wavelength of the light of very distant objects is stretched (redshifted), so these objects can no longer be seen in the primarily ultraviolet and visible portions of the spectrum Hubble was designed to detect. Finally, theory suggests early galaxies were smaller and fainter to begin with and only later merged to form the colossal structures we see today. Scientists are confident these galaxies exist. We just don’t know how many there are.

In 2016, a study published in The Astrophysical Journal by a team led by the University of Nottingham’s Christopher Conselice used a mathematical model of the early universe to estimate how many of those as-yet-unseen galaxies are lurking just beyond Hubble’s sight. Added to existing Hubble observations, their results suggested such galaxies make up 90 percent of the total, leading to a new estimate—that there may be up to two trillion galaxies in the universe.

Such estimates, however, are a moving target. As more observations roll in, scientists can get a better handle on the variables at play and increase the accuracy of their estimates.

Which brings us to the most recent addition to the story.

After buzzing by Pluto and the bizarre Kuiper Belt object, Arrokoth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft is at the edge of the solar system cruising toward interstellar space—and recently, it pulled a Hubble. In a study presented this week at the American Astronomical Society and soon to be published in The Astrophysical Journal, a team led by astronomers Marc Postman and Tod Lauer described what they found after training the New Horizons telescope on seven slivers of empty space to try and measure the level of ambient light in the universe.

Their findings, they say, allowed them to establish an upper limit on the number of galaxies in existence and indicate space may be a little less crowded than previously thought. According to their data, the total number of galaxies is more likely in the hundreds of billions, not trillions. “We simply don’t see the light from two trillion galaxies,” Postman said in a release published earlier in the week.

How did they arrive at their conclusion?

The Search for Perfect Darkness

There is one more constraint on Hubble’s observations. Not only can’t it directly resolve early galaxies, it can’t even detect their light due to the diffuse glow of “zodiacal light.” Caused by a halo of dust scattering light within the solar system, zodiacal light is extremely faint, but just like light pollution on Earth, it can obscure even fainter objects in the early universe.

The New Horizons spacecraft has now escaped the domain of zodiacal light and is gazing at the darkest sky yet imaged. This offers the opportunity to measure the background light from beyond our galaxy and compare it to known and expected sources.

Postman told The New York Times that going an order of magnitude further wouldn't have offered a darker view.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“When you have a telescope on New Horizons way out at the edge of the solar system, you can ask, how dark does space get anyway,” Lauer wrote. “Use your camera just to measure the glow from the sky."

Still, the measurement was not straightforward. In an article, astrophysicist and writer Ethan Siegel, who was not part of the study, explains how the team meticulously identified, modeled, and removed contributions from “camera noise, scattered sunlight, excess off-axis starlight, crystals from the spacecraft’s thrust, and other instrumental effects.” They also removed any images too close to the Milky Way. After all this, they were left with the faint glow of the universe, and that’s the exciting bit.

The 2016 study predicted that a universe with two trillion galaxies would produce about ten times more light than the galaxies we’ve so far observed indicate. But the New Horizons team only found about twice as much light. This led them to their conclusion there are likely fewer total galaxies lurking out there than previously thought—a number closer to the original Hubble estimate.

“Take all the galaxies Hubble can see, double that number, and that’s what we see—but nothing more,” said Lauer.

Star Gazing: The Next Generation

These observations from New Horizons aren't the end of the story. Our ability to view the earliest universe should get a leg up this year when (fingers crossed) Hubble’s successor, the James Webb Space Telescope will launch and begin operations.

The JWST is set to observe in longer wavelengths than Hubble and is much bigger. These attributes should allow it to see even further back and image those smaller, fainter first galaxies. Like the Hubble Deep Field, if all is in working order, adding those galaxies to the census should give us an even clearer picture of the whole.

Whatever number scientists finally land on, it's unlikely to be anything but mind-bogglingly huge. Even a few hundred billion galaxies means there's an entire galaxy out there for every star in the Milky Way. Such research will undoubtedly cast even more light on cosmological questions about how the universe formed. But it will also beg the question: Amid the vast sea of galaxies, stars, and planets, are we really the only species to ever look out and wonder if we're alone?

Image Credit: eXtreme Deep Field / NASA

Jason is editorial director at SingularityHub. He researched and wrote about finance and economics before moving on to science and technology. He's curious about pretty much everything, but especially loves learning about and sharing big ideas and advances in artificial intelligence, computing, robotics, biotech, neuroscience, and space.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

What If We’re All Martians? The Intriguing Idea That Life on Earth Began on the Red Planet

The Era of Private Space Stations Launches in 2026

What we’re reading