A Swedish Company Wants to Transform Offshore Wind With Vertical-Axis Turbines

Share

Even as more offshore wind projects launch and the turbines they use get bigger, there are questions around offshore wind’s economic viability. Unsurprisingly, hauling huge equipment with multiple moving parts out to deep, windy sections of ocean, setting them up, and building lines to transmit the electricity they generate back to land is expensive. Really expensive. In our profit-driven capitalist economy, companies aren’t going to sink money into technologies that don’t deliver worthwhile returns.

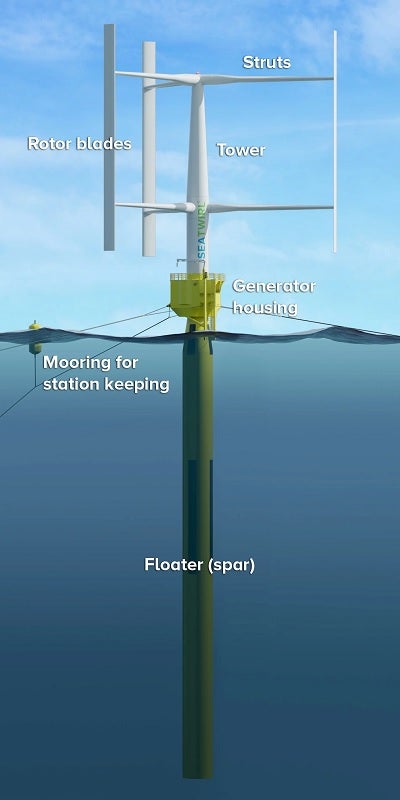

A Swedish energy company called SeaTwirl is flipping the offshore wind model on its head—not quite literally, but almost—and betting it will be able to deliver cheap renewable energy and make a profit along the way. SeaTwirl is one of several companies developing vertical-axis wind turbines, and one of just a couple developing them for offshore use.

A quick refresher on what vertical axis means: the turbines we’re used to seeing (that is, on land, at a distance, often from an interstate highway or rural road), have horizontal axes; like windmills, their blades spin between parallel and perpendicular to the ground, anchored by a support column that’s taller than the diameter covered by the spinning blades.

Bigger means better when it comes to efficiency, so these turbines have gotten huge both on land and at sea. But there are some technical and design limitations to how big they can get. Their generators need to be located at their main axle near the top of the support tower. This adds a lot of weight at the top of the tower, which requires even more weight at the bottom (and significant strength along the tower’s entire height) to keep the whole thing from toppling over or bending in half.

SeaTwirl's vertical-axis turbine design. Image Credit: SeaTwirl

The generator in a vertical-axis turbine, on the other hand, can be placed anywhere on said vertical axis; in an offshore context, this means it can be at the waterline or below, adding weight where weight is needed.

Vertical-axis turbines can also use wind coming from any direction. Since their rotation doesn’t take up as much space as that of horizontal-axis turbines nor create as much of a blocking effect on downwind turbines, they can be placed closer together, generating more electricity in a given footprint.

SeaTwirl was founded in 2012, and for the past seven years it’s been proofing a test version of its vertical-axis turbine off the coast of Lysekil, a seaside town on Sweden’s western side. Called S1, the turbine has a generating capacity of 30 kilowatts, and its above-water portion is 43 feet (13 meters) tall, with another 59 feet (18 meters) submerged. It has fed an onshore grid throughout its trial period, while withstanding hurricane-level winds and waves.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

With this success under its belt, SeaTwirl now wants to go bigger—a lot bigger. It’s preparing to build a turbine called the S2x, which will be able to generate one megawatt of electricity and will serve as a pilot for the company’s first commercial product.

The turbine will rise 180 feet (55 meters) out of the water, and its weighted central pole will reach 262 feet (80 meters) below the surface. That’s a total height of 442 feet. For perspective, the Statue of Liberty is 305 feet tall including the base and foundation. The vertical-axis turbine is still dwarfed by its horizontal-axis counterparts, though; GE’s Haliade-X is 853 feet tall, and Chinese MingYang Smart Energy Group is building a turbine that’s even a few feet taller.

The S2x will be placed in waters at least 328 feet deep, and designed to withstand category-two hurricane winds. SeaTwirl estimates the turbine will have a service life of 25 to 30 years, and the first one will be located off the coast of Bokn, Norway. It's expected to be commissioned in 2023 for a test period of around five years, and the company says it will generate energy at a cost that’s competitive with other offshore turbines.

If the S2x is as successful as the S1, SeaTwirl will aim to scale up even more, possibly to turbines in the six to ten-megawatt range by 2025.

Image Credit: SeaTwirl

Vanessa has been writing about science and technology for eight years and was senior editor at SingularityHub. She's interested in biotechnology and genetic engineering, the nitty-gritty of the renewable energy transition, the roles technology and science play in geopolitics and international development, and countless other topics.

Related Articles

Startup Zap Energy Just Set a Fusion Power Record With Its Latest Reactor

Scientists Say New Air Filter Transforms Any Building Into a Carbon-Capture Machine

Investors Have Poured Nearly $10 Billion Into Fusion Power. Will Their Bet Pay Off?

What we’re reading