Has the Lunar Gold Rush Begun? Why the First Private Moon Landing Matters

Share

People have long dreamed of a bustling space economy stretching across the solar system. That vision came a step closer last week after a private spacecraft landed on the moon for the first time.

Since the start of the space race in the second half of last century, exploring beyond Earth’s orbit has been the domain of national space agencies. While private companies like SpaceX have revolutionized the launch industry, their customers are almost exclusively satellite operators seeking to provide imaging and communications services back on Earth.

But in recent years, a growing number of companies have started looking further afield, encouraged by NASA. The US space agency is eager to foster a commercial space exploration industry to help it lower the cost of upcoming missions.

And now, the program has started paying dividends after a NASA-funded mission from startup Intuitive Machines saw their Nova-C lander, which they named Odysseus, become the first privately developed spacecraft to successfully complete a soft landing on the moon’s surface.

“We’ve fundamentally changed the economics of landing on the moon,” CEO and cofounder Steve Altemus said at a news conference following the landing. “And we’ve kicked open the door for a robust, thriving cislunar economy in the future.”

Despite the momentous nature of the achievement, the touchdown wasn't as smooth as the company may have hoped. Odysseus came in much faster than expected and missed its intended landing spot, which resulted in the spacecraft toppling over on one side. That meant some of its antennae ended up pointing at the ground, limiting the vehicle’s ability to communicate.

It turned out that this was because engineers had forgotten to flick a safety switch before launch, disabling the spacecraft’s range-finding lasers. This meant they had to jury rig a new landing system that relied on optical cameras while the mission was already underway. The company acknowledged to Reuters that a pre-flight check of the lasers would have averted the problem, but this was skipped because it would have been time-consuming and costly.

In hindsight, that might seem like an easily avoidable hiccup, but this kind of cost-consciousness is exactly why NASA is backing smaller private firms. The mission received $118 million from the agency via its Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program, which is paying various private space firms to ferry cargo to the moon for its upcoming, manned Artemis missions.

The Intuitive Machines mission cost around $200 million, which is significantly less than what a NASA-led mission would. But it’s not just bargain prices the agency is after; it also wants providers that can launch more quickly, and the redundancy that comes from having multiple options.

Other companies involved include Astrobotic, which nearly clinched the title of first private company on the moon before propulsion problems scuppered its January mission, and Firefly Aerospace, which is due to launch its first cargo mission later this year.

NASA leaning on private companies to help complete its missions is nothing new. But both the agency and the companies themselves see this as something more than simple one-off launch contracts.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

"The goal here is for us to investigate the moon in preparation for Artemis, and really to do business differently for NASA," Sue Lederer, CLPS project scientist said during a recent press conference, according to Space.com. "One of our main goals is to make sure that we develop a lunar economy."

What that economy would look like is still unclear. Alongside NASA instruments, Odysseus was carrying six commercial payloads, including sculptures made by artist Jeff Koons, a "secure lunar repository" of humanity's knowledge, and an insulating material called Omni-Heat Infinity made by Columbia Sportswear.

Writing for The Conversation, David Flannery, a planetary scientist at Queensland University of Technology in Australia, suggests that once the novelty wears off, more publicity-focused payloads may prove to be an unreliable source of income. Government contracts will likely make up the bulk of these companies’ revenue, but for a true lunar economy to get into gear, that won’t be enough.

Another possibility that’s often touted is mining for local resources. Candidates include water ice, which can be used to support astronauts or create hydrogen fuel for rockets, or helium-3, a material that can be used to create ultra-cold cryogenic refrigerators or potentially be used as fuel in putative future fusion reactors.

Whether that ever turns out to be practical remains to be seen, but Altemus says the rapid progress we’ve seen since the US declared the moon a strategic interest in 2018 makes him optimistic.

“Today, over a dozen companies are building landers,” he told the BBC. “In turn, we've seen an increase in payloads, science instruments, and engineering systems being built for the moon. We are seeing that economy start to catch up because the prospect of landing on the moon exists."

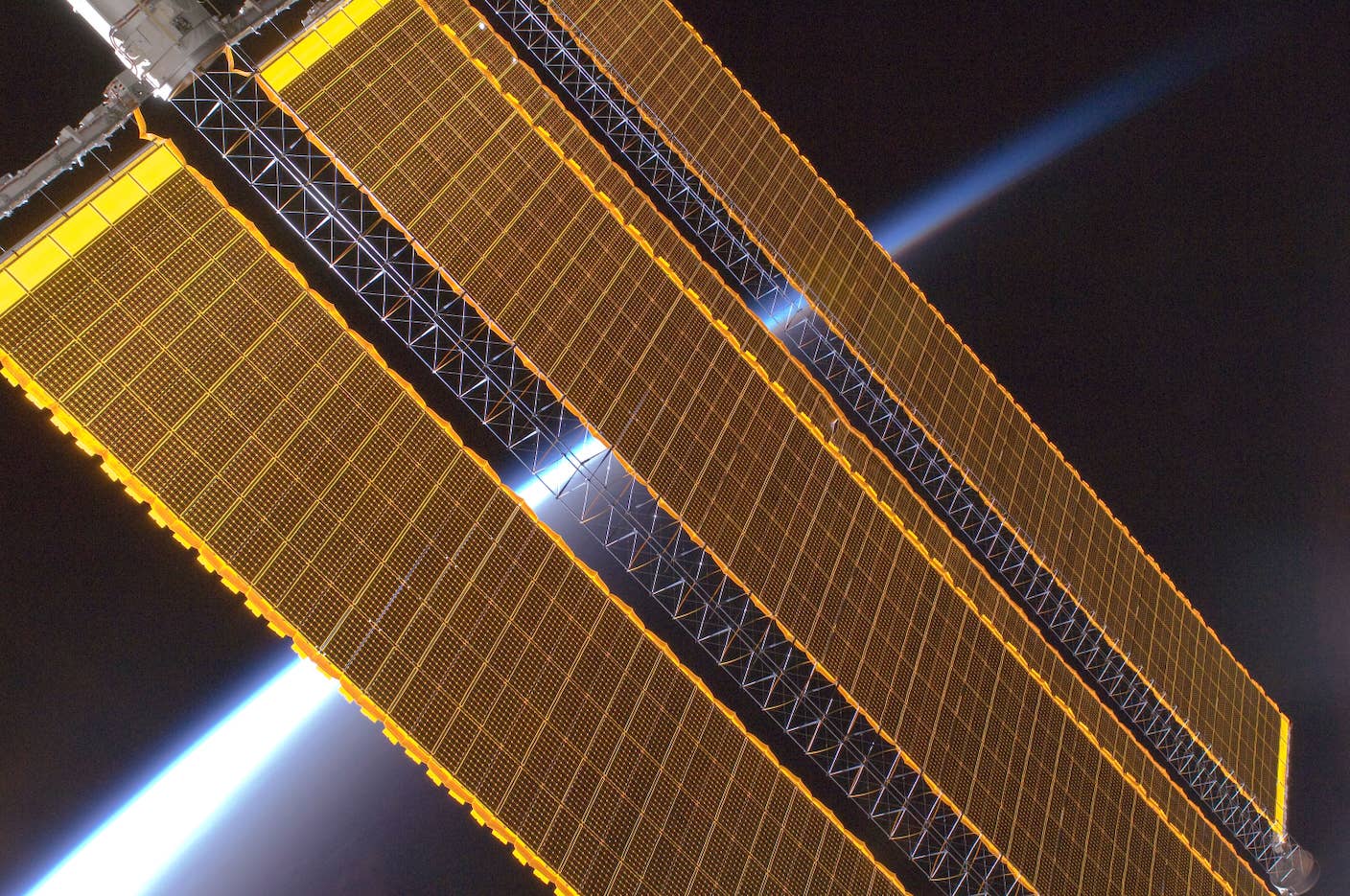

Image Credit: NASA JPL

Related Articles

Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

Scientists Say We Need a Circular Space Economy to Avoid Trashing Orbit

New Images Reveal the Milky Way’s Stunning Galactic Plane in More Detail Than Ever Before

What we’re reading