Ozempic-Like Drug Slows Cognitive Decline in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

Share

If you hear the word Ozempic, weight loss immediately comes to mind. The drug—part of a family of treatments called GLP-1 agonists—took the medical world (and internet) by storm for helping people manage diabetes, lower the risk of heart disease, and rapidly lose weight.

The drugs may also protect the brain against dementia. In a clinical trial including over 200 people with mild Alzheimer’s disease, a daily injection of a GLP-1 drug for one year slowed cognitive decline. When challenged with a battery of tests assessing memory, language skills, and decision-making, participants who took the drug remained sharper for longer than those who took a placebo—an injection that looked the same but wasn’t functional.

The results are the latest from the Evaluating Liraglutide in Alzheimer’s Disease (ELAD) study led by Dr. Paul Edison at Imperial College London. Launched in 2014, the study was based on years of research in mice showing liraglutide—a GLP-1 drug already approved for weight loss and diabetes management in the United States—also protects the brain.

In Alzheimer’s disease, neurons die off and the brain gradually loses volume. In the trial, Liraglutide slowed the process down, resulting in roughly 50 percent less volume lost in several areas of the brain related to memory compared to a placebo.

“We are in an era of unprecedented promise, with new treatments in various stages of development that slow or may possibly prevent cognitive decline due to Alzheimer’s disease,” said Dr. Maria C. Carrillo, Alzheimer’s Association chief science officer and medical affairs lead, in a press release. “This research provides hope that more options for changing the course of the disease are on the horizon.”

The results were presented last month at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference.

Back to Basics

The quest for an Alzheimer’s disease treatment is littered with failures. Most treatments aim to tackle toxic protein clumps that build up inside the brain. It’s thought that breaking them up could prevent neurons from withering away.

A few have had limited success. Last month, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a drug that breaks down the clumps in people already experiencing symptoms at an early stage of the disease. A few weeks later, the European Medicines Agency refused to approve another drug that also targets the clumps, saying the effects of delaying cognitive decline didn’t balance the risk of serious side effects, including brain swelling and bleeding.

Other scientists have looked elsewhere—specifically, diabetes. Insulin helps maintain brain health, and Type 2 diabetes is a risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease. Rather than directly breaking down protein clumps in the brain, might we protect the brain by tweaking the body’s metabolism?

Enter GLP-1 drugs. These mimic hormones released by the stomach after a satisfying meal, tricking the brain into thinking you’re full. In other words, the drugs don’t only influence the gut—they also change brain functions.

In a mouse model of Alzheimer’s, daily injections of liraglutide for eight weeks prevented memory problems. Their neurons also thrived. Synapses—the junctions connecting brain cells—were still able to rapidly form neural networks in areas especially damaged by the disease. Surprisingly, toxic protein clumps also declined by up to 50 percent, and inflammation dropped.

Liraglutide didn’t just work on neurons. Another study, also in an Alzheimer’s mouse model, found it rapidly tweaked the metabolism of a particular kind of star-shaped brain cell that supports neurons. These cells don’t form neural networks, but they do help provide energy. In Alzheimer’s, they stop functioning normally, but liraglutide reversed the decline. In mice, the drug improved the cells’ ability to support neurons, allowing the neurons to flourish and connect to others. The brain also made better use of sugar—its primary fuel—allowing it to give birth to new neurons in a region important for memory.

But as the field frustratingly knows, mice are not people. Many promising treatments in mice have failed in clinical studies, earning these endeavors the nickname “graveyard of dreams.”

The Trial

Edison took on the task of extending the research from mice to humans. In 2019, he and his colleagues detailed plans for a clinical trial to gauge liraglutide’s effects in people with mild Alzheimer’s. Called ELAD, the study was to be randomized and double-blind—the gold standard in clinical trials. Here, neither doctor nor patient knows who’s getting liraglutide or the placebo.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

They recruited 204 people to receive injections, either liraglutide or placebo, every day for a year. Before the trial, each person had an MRI scan to map their brain’s structure and volume. Other scans recorded brain metabolism, and a battery of memory tests detailed cognition. These tests were repeated at the end, with safety checkups in between, in case of side effects.

The study had several goals. One was to see if liraglutide increased the brain’s metabolism in regions heavily impacted by Alzheimer’s—those related to learning, memory, and decision-making. Another examined brain volume, which decreases as the disease progresses. The last evaluated cognitive tests of memory, comprehension, language, and spatial navigation.

People who took liraglutide had nearly 50 percent less brain volume loss, especially in regions associated with reasoning and learning. “The slower loss of brain volume suggests liraglutide protects the brain, much like statins protect the heart,” said Dr. Edison.

Liraglutide also boosted cognition. Comparing scores from before the trial, at its midpoint, and at the end, those who received the drug had an 18 percent slower decline than those who took the placebo. However, the drug didn’t affect brain metabolism.

Side effects were relatively mild. The most common was nausea. More serious ones, not specified, occurred in 18 patients but weren’t likely related to the treatment according to Edison.

To be clear, the team presented the results at a conference, and they haven’t yet been formally vetted by other experts in the field. But they add to accumulating evidence that GLP-1 drugs slow cognitive decline. A Swedish study in June conducted a simulated trial in people with Type 2 diabetes given GLP-1 or two other types of drugs and assessed their cognition afterward. Using health data records from over 88,000 participants followed over four years, GLP-1 drugs were better than the two other diabetes drugs at keeping the risk of dementia at bay.

We don’t yet know how liraglutide protects the brain. Based on studies in mice, it likely works multiple ways, such as reducing inflammation, clearing toxic protein clumps, and improving communicate between neurons, Edison said.

But the idea is gaining steam. EVOKE Plus, a late stage clinical trial of semaglutide—the chemical in Ozempic—is ongoing. The study will take about three and a half years, with an estimated enrollment of 1,840 people with early Alzheimer’s disease. It’s set to conclude in late 2026.

“Repurposing drugs already approved for other conditions has the advantage of providing data and experience from previous research and practical use—so we already know a lot about real-world effectiveness in other diseases and side effects,” said Carrillo.

Image Credit: Maxim Berg / Unsplash

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

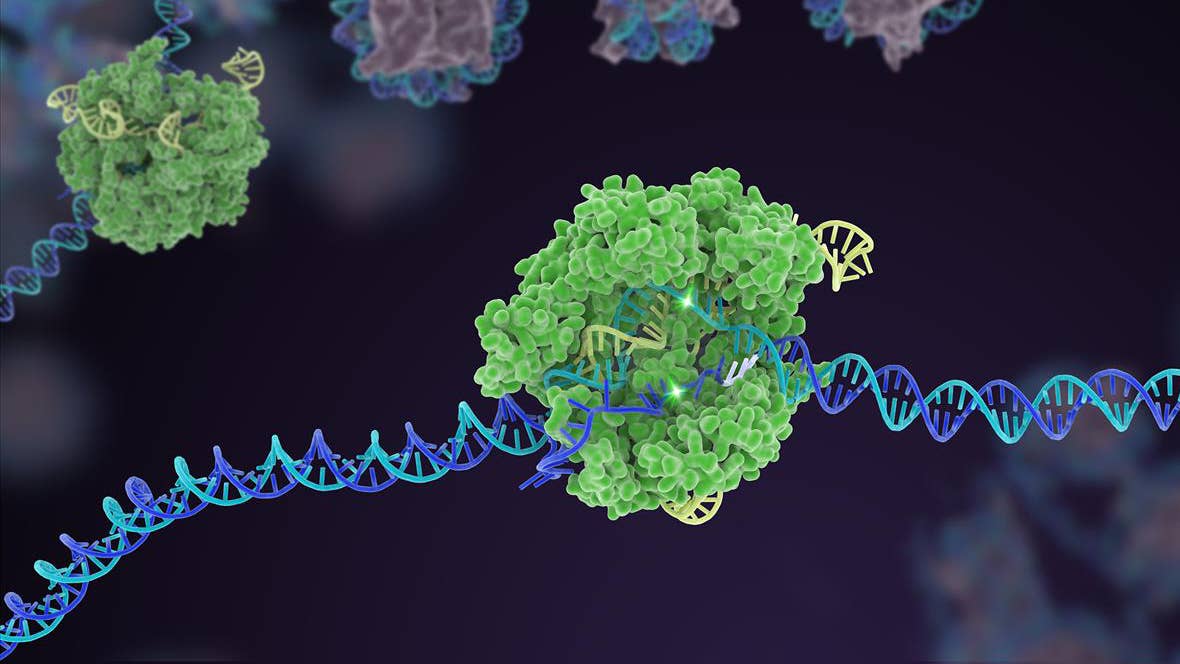

Souped-Up CRISPR Gene Editor Replicates and Spreads Like a Virus

Your Genes Determine How Long You’ll Live Far More Than Previously Thought

Google DeepMind AI Decodes the Genome a Million ‘Letters’ at a Time

What we’re reading