A Novel Treatment Slashes HIV Up to 10,000-Fold in Monkeys With Just a Single Dose

Share

Thanks to antiviral medications, HIV infection is no longer a death sentence. With a cocktail of drugs, people with HIV can keep the virus in check. Introduced more recently, PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, can guard uninfected people from potential infections.

The pills, taken with a sip off water, have protected pregnant women at high risk of HIV. The treatment also dramatically slashes the risk of catching the virus in other populations.

But antivirals come with side effects. Nausea, fatigue, dizziness, and pain are common. When taken for years—which is typical—the drugs raise cholesterol levels and increase the chances of depression, diabetes, and liver and kidney damage. They’re also expensive and very hard to come by in some regions of the world. As an alternative, scientists have long been working on an HIV vaccine, but so far to no avail.

This week, an international team led by Dr. Leor Weinberger at the University of California, San Francisco, tapped into an age-old idea in the battle against viruses, but with a modern twist.

One way to make vaccines is to create viruses stripped of harmful traits but still able to infect cells. In the new study, scientists built on this idea to develop a one-shot antiviral HIV therapy. By removing HIV’s disease-causing genes, the team created “benevolent twins” called TIPs—or therapeutic interfering particles—which outcompete HIV and limit its ability to reproduce.

A single shot of TIPs reduced the amount of virus inside infected monkeys by up to 10,000-fold and helped the treated animals live longer.

The new approach is a virus-like living drug. Like its evil twin, HIV, it replicates and spreads in the body. Because both viruses use the same cell machinery to reproduce, the engineered virus dominates precious resources, elbowing out disease-causing viruses and limiting their spread. TIPs also kept the virus’s levels at bay in cells from HIV-positive people.

Plans are underway to test the idea in humans. If safe and effective, the long-lasting shot could help people who don’t have regular access to antiviral drugs.

ART to TIPs

HIV is a formidable enemy. The virus rapidly evolves and spins out variants that outcompete efforts to combat it.

Scientists have long sought an HIV vaccine. Although several vaccines are in clinical trials, so far the virus has largely stymied researchers.

Antiviral drugs have had a better run. Dubbed ART, for antiretroviral therapy, these involve taking multiple medications every day to keep the virus at bay. The drugs have been game-changers for people with HIV. But they don’t cure the disease, and missing doses can reignite the virus.

Several new ideas are in the works. In 2019, stem cell implants freed three people of the virus. The implants came from people with a genetic mutation that naturally fights HIV. In July, a seventh person was reportedly “cured” of HIV using a similar strategy—although the donor cells only had one copy of the HIV-resistant gene, rather than two copies in previous cases.

While promising, cell therapies are expensive and technically difficult. Over a decade ago, Weinberger came up with a novel idea: Give people already infected with HIV a stripped-down variant without the ability to cause harm. Because both viruses require the same resources to reproduce, the benign twin could outcompete the deadly version.

“I think we need to try something new,” he recently told Science.

Tipping Point

HIV requires cells to replicate.

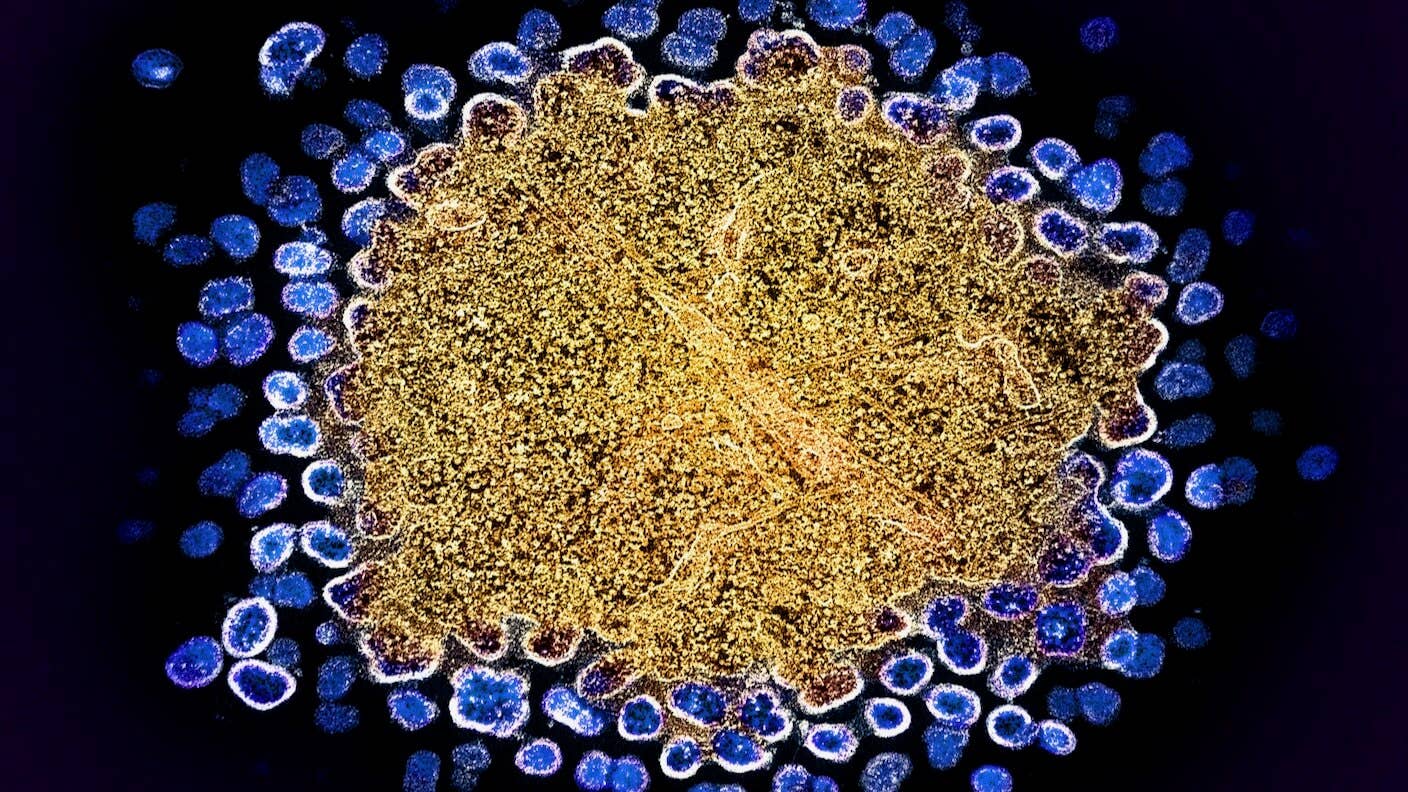

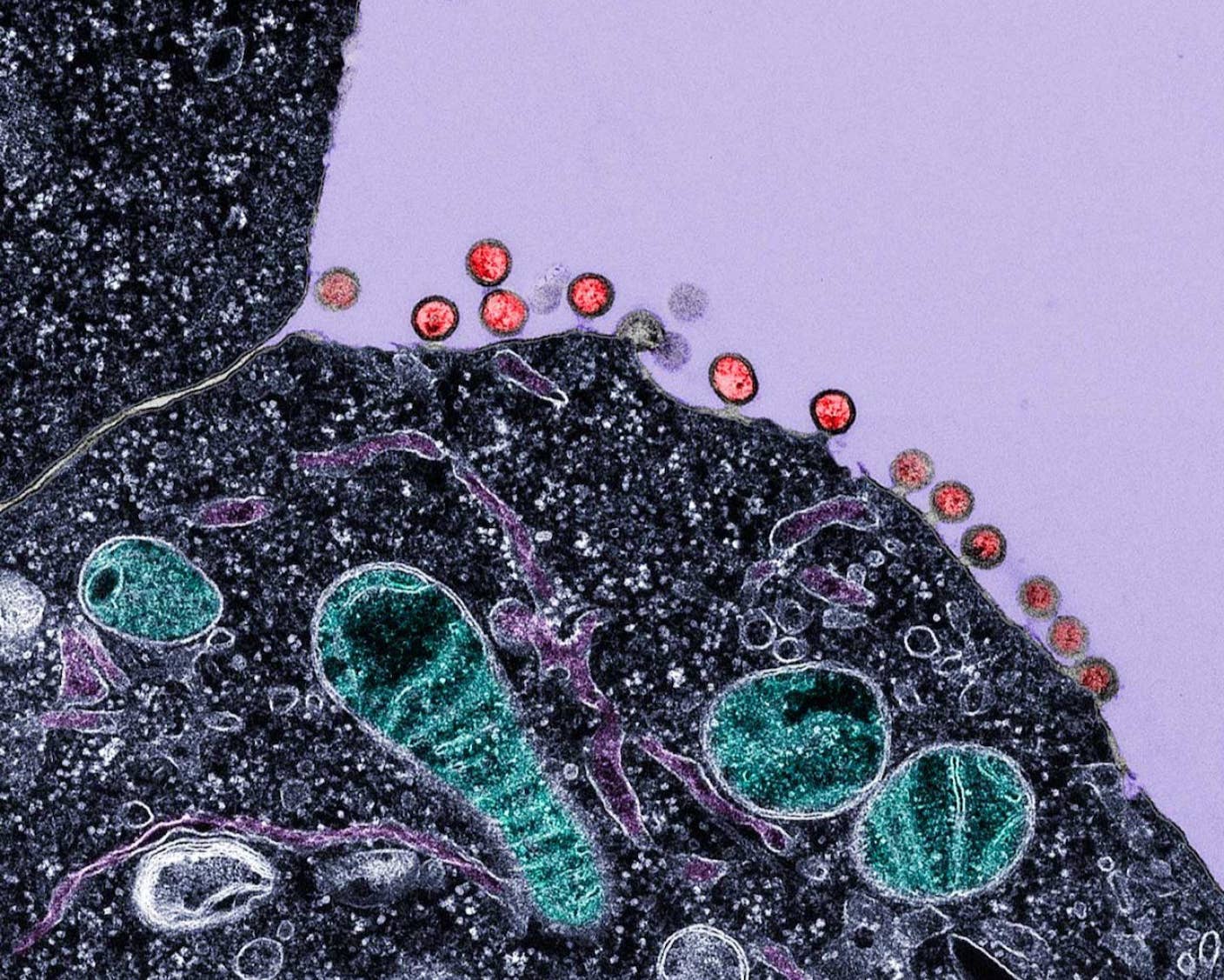

The virus grabs onto a type of immune cell and pumps its genetic material into the host. Then, hijacking the machinery in these cells, the virus integrates its DNA into the genome. The cells replicate these viral genes and assemble them into a new generation of sphere-like viruses, ready to be released into the bloodstream to further multiply and spread.

However, the entire process relies on limited resources. Here’s where TIPs come in.

The team grew HIV particles in petri dishes and deleted disease-causing genes over multiple generations. They were finally left with stripped-down versions of HIV, or TIPs.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

In a way, the neutered HIV becomes a parasite that can fight off the natural virus. Because TIPs have fewer genetic letters, they replicate more quickly than natural HIV, allowing them to flood the cell and spread in lieu of their natural counterparts.

In a test, the team injected TIPs into six young macaque monkeys, infected with a synthetic monkey version of HIV a day later. After 30 weeks, in five treated monkeys, the single-shot treatment reduced the amount of virus in the watery part of their blood, or plasma, 10,000-fold. Viral levels also tanked in lymph nodes, where HIV swarms and replicates. In contrast, those who went untreated got increasingly sick.

A computer model translated these results for human therapy, suggesting TIPs could reduce HIV 1,000-fold or more in humans. Although not as dramatic as in monkeys, the single-shot treatment could reduce the virus to levels so low it couldn’t be transmitted to others.

A New Therapy?

Many people with HIV are already on antiviral drugs.

The team next asked if their shot could replace these drugs. In cells in petri dishes, they found TIPs sprang into action once the drugs were removed, limiting HIV growth and protecting cells.

In cells infected with multiple strains of HIV, the strains swap DNA and rearrange their genetic material, which is partly why HIV is so hard to tame with vaccines. Antiviral drugs can trigger this response and eventually cause resistance. TIPs, in contrast, seem to keep it at bay.

TIPs isn’t the only new treatment in town. Long-acting HIV drugs are in clinical trials, with some needing only two shots a year. But these still rely on antiviral drugs.

To be clear, TIPs doesn’t cure HIV. Like antiviral drugs, it keeps the virus at bay. But rather than taking a cocktail of pills every day, a single jab could last months with lower chance of resistance.

There are downsides, however. Like HIV, TIPs can be transmitted to others through bodily fluids, raising ethical issues about disclosure. The shots could also lead to dangerous immune flareups, although this didn’t happen in the monkey studies.

The team is planning to study potential toxicity to the genome and inflammation and further investigate how TIPs work once antiviral drugs have been halted in monkeys.

They’re also looking to recruit people with HIV, and another terminal illness, to test the effects of TIPs after stopping antiviral drugs. The goal is to begin the trial next year.

"The real test, of course, will be the upcoming human clinical trials," said Weinberger in a press release. “But if TIPs prove effective, we could be on the brink of a new era in HIV treatment that could bring hope to millions of people—particularly in areas where access to antiviral drugs remains a challenge."

Image Credit: HIV (blue) replicating from a T Cell (gold). NIAID / Flickr

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

Scientists Just Developed a Lasting Vaccine to Prevent Deadly Allergic Reactions

What we’re reading