World’s Biggest Battery Will Provide 85 Megawatts to New England Grid

Share

The rapid transition to renewable energy is great news for the environment, but electrical grids are struggling to incorporate intermittent power sources like wind and solar. Startup Form Energy is about to demonstrate a potential solution with the construction of the world's largest battery.

While gas- and coal-powered plants can run night and day, renewable power is highly reliant on the sun shining and the wind blowing. Finding ways to deal with this inherent uncertainty will be crucial if we ever want to fully decarbonize our grids.

One of the most obvious solutions is to store extra energy when conditions are favorable, so it can be fed back into the grid later when renewable production drops off. But building batteries capable of storing grid-scale quantities of electricity presents both engineering and economic challenges.

So far, most grid-storage facilities rely on lithium-ion batteries—the same technology found in cellphones and electric vehicles. But these batteries are relatively expensive and not particularly long-lived. They’re also prone to setting fire, which makes them less than ideal for such projects.

Form Energy is betting that its novel iron-air chemistry, which is specially designed for long-term energy storage, could be the answer. And it’s now set to receive $147 million to build a facility in Maine capable of storing enough energy to provide 85 megawatts of power for up to 100 hours.

“Located at the site of a former paper mill in rural Maine, this iron-air battery system will have the most energy capacity of any battery system announced yet in the world,” Mateo Jaramillo, CEO and cofounder of Form Energy, said in a press release.

The project, which is due to be complete by 2028, is part of a broader package of funding from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to upgrade the power grid in the Northeast of the US. Most of the $389 million will be used to expand and upgrade the region’s ability to accept power from large offshore wind farms. But the remainder will be given to Form to build a facility capable of storing 8,500 megawatt-hours of energy.

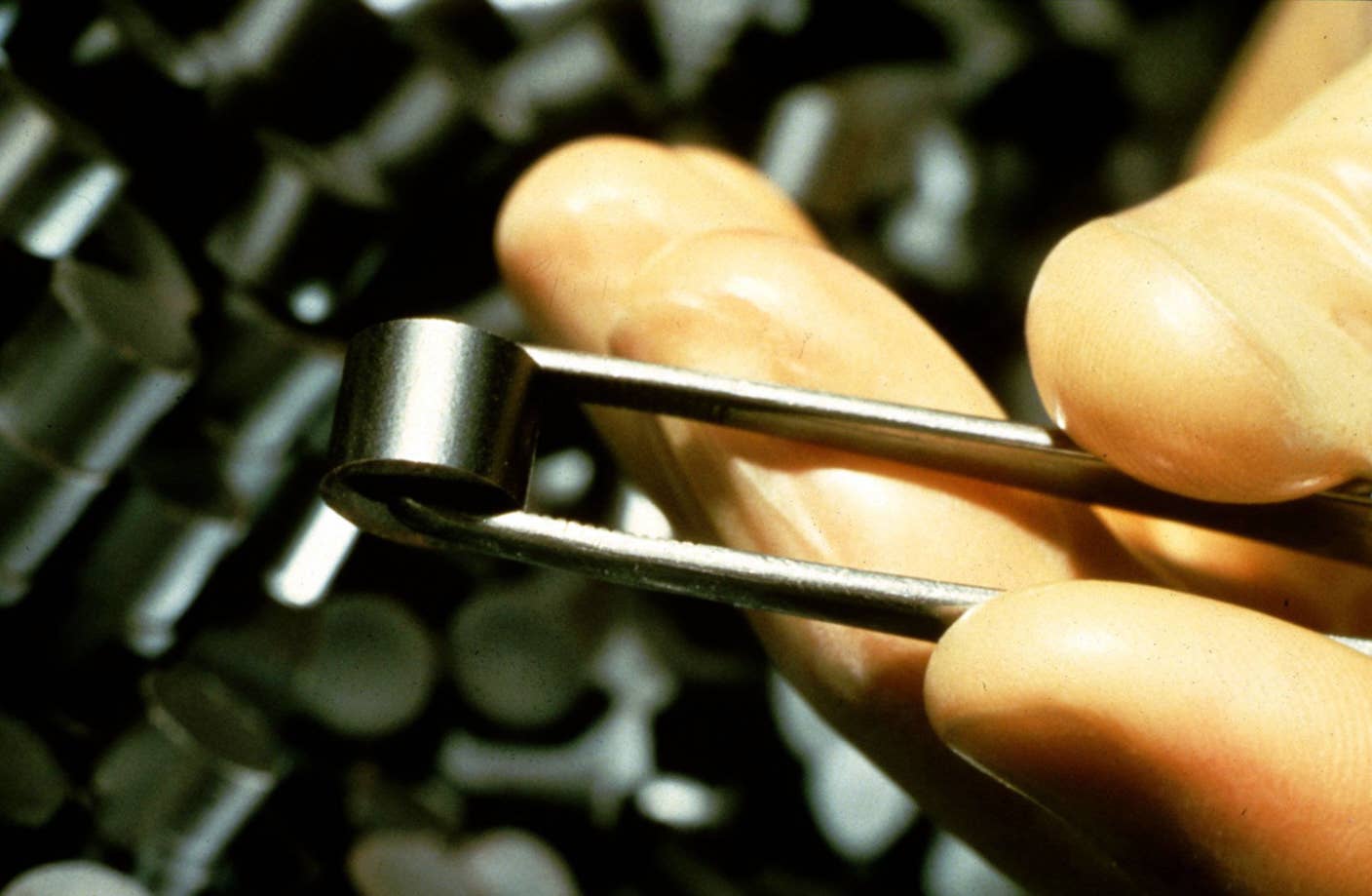

The key ingredients of the company’s battery cells are iron and water, and they rely on the same process that causes rust to charge and discharge. Energy is stored in the battery by converting iron oxide into pure iron and emitting the oxygen into the atmosphere. To release that energy, the battery absorbs oxygen from ambient air to turn the iron back into iron oxide.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

This approach can’t get anywhere close to the energy density of lithium-ion batteries—a crucial consideration when packing batteries into small devices or trying to boost the range of vehicles. But when building large-scale storage systems energy density is much less of a concern than cost, a metric on which iron-air batteries win hands down.

Form says this will allow it to build storage facilities that can act as substitutes for power plants for extended periods. As well as helping to balance the grid during everyday operations, this could also help provide emergency power during extreme weather or other grid outages.

While the Maine project is the most ambitious that Form has announced to date, the company has already announced other smaller pilot projects, and Jaramillo told Canary Media that it’s working on other grid-scale facilities of a similar size that have yet to be publicized.

Given the company is still building the factory that will supply batteries to all these projects, it’s early days for the approach. If all goes according to plan though, it could prove to be a crucial tool in efforts to decarbonize the grid.

Image Credit: Form Energy

Related Articles

Meta Will Buy Startup’s Nuclear Fuel in Unusual Deal to Power AI Data Centers

Your ChatGPT Habit Could Depend on Nuclear Power

Hugging Face Says AI Models With Reasoning Use 30x More Energy on Average

What we’re reading