Elderly Monkeys Aged More Slowly When Given a Cheap Diabetes Drug Used by Millions

Share

A drug that slows aging may already be on the market.

Scientists have long been interested in metformin, a widely prescribed drug used to treat Type 2 diabetes, for its potential to delay aging. In worms, fruit flies, and rodents, the drug—on average less than a dollar per pill—shows promising anti-aging effects.

Last week, a study in Cell added to the evidence that metformin could slow the ravages of time. Scientists gave male monkeys aged the equivalent of 52 to 64 in human years a daily pill for three years and monitored their physical health and cognition.

Compared to naturally aging monkeys, metformin preserved their learning and memory abilities, reduced brain shrinkage, and restored their neurons to a more youthful state. The monkeys’ “brain age” was dialed back by almost 6 years, or around 18 human years.

Metformin’s effects extended beyond the brain. The drug reduced chronic inflammation—a hallmark of aging—in multiple tissues, slowed liver aging, and boosted cellular mechanisms that protect the liver. Kidneys, lungs, and muscles were also “rescued” from age-related problems, their gene expression profiles reverting to more youthful ones.

The study bridges the gap between rodents and primates. The dosages of metformin given were on par with those for diabetes management and could inform upcoming clinical trials.

To be clear, the study did not examine longevity, that is, how long the monkeys lived. Rather, it focused on the slowing of age-related diseases, with the results contributing to our understanding of health span—the number healthy living years people experience.

This study is the “most quantitative, thorough examination of metformin action that I’ve seen beyond mice,” Dr. Alex Soukas at Massachusetts General Hospital told Nature, who was not involved in the study.

Old Dog, New Tricks

Metformin may have a shiny new reputation for battling aging, but it’s already had a long life in medicine.

First extracted from a plant called goat’s rue, a traditional herbal medicine in Europe, researchers in 1918 found it lowered blood sugar. Three decades ago, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved it for Type 2 diabetes.

But metformin’s effects on the body extend beyond blood sugar management. It works through multiple molecular pathways to control cell growth, metabolism, and inflammation—all of which go haywire during aging. This made scientists wonder: Can the drug slow aging?

Initial studies in several animal models of aging showed promise. Repeated doses of the drug reversed age-related tissue damage. In humans, epidemiological studies have found the drug reduces the risk of cancer and dementia. A 2014 study of 78,000 people showed that, on average, people with Type 2 diabetes on metformin lived longer than those of the same age who didn’t have diabetes and didn’t take the drug.

Despite its potential for slowing age-related disease, metformin hasn’t yet been directly tested in primates with that in mind.

Monkey Business

The new study filled that gap. The team gave metformin to crab-eating male macaque monkeys, which usually have a lifespan of roughly 25 to 30 years.

The treatment was simple: Beginning at around the equivalent of 52 to 64 years old in humans, some of the monkeys were fed a daily pill of metformin, similar in dosage to that used in diabetes management. Others didn’t receive the drug and aged naturally. For comparison, the team also included a young-adult and a middle-aged group.

All groups received comprehensive physical exams throughout the trial. These included a staggering 65 health measures, such as BMI, blood tests, and imaging of their bodies and brains.

The oldest groups, either with or without metformin, were also given a barrage of cognitive tests. Some checked their ability to remember things after a delay. Others tested how well they learned new information or could update previous knowledge—a measure of flexible thinking that erodes with age.

The team watched the monkeys’ health for over three years—or roughly the equivalent of 13 human years—while collecting samples of gene expression and protein data from multiple organs and tissues.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Comparing old monkeys treated with metformin to young, middle-aged, and untreated elderly ones, the team generated a “rescue score”—that is, how much metformin slowed aging. The brain, skin, liver, kidney, and lungs were the most restored according to the analysis.

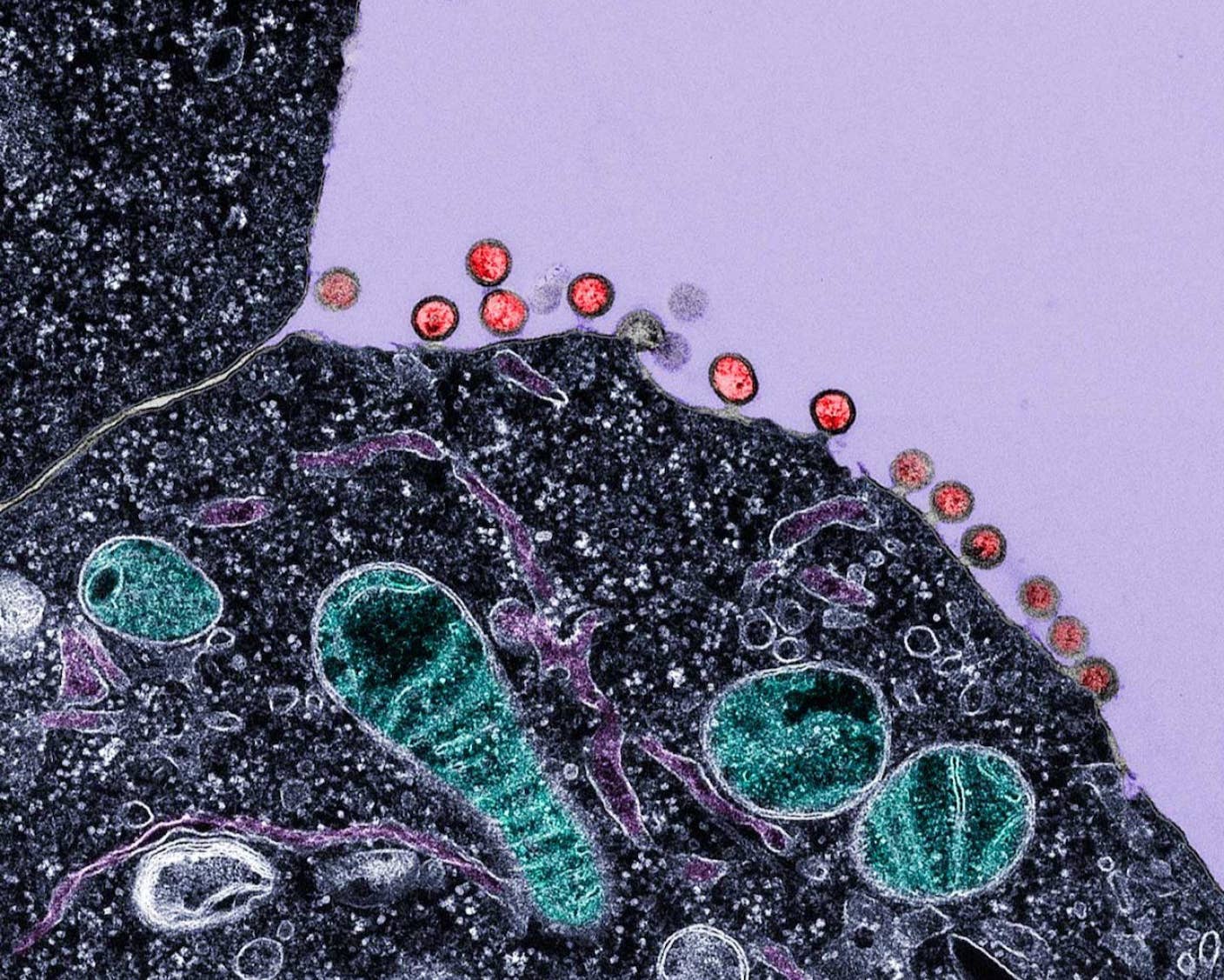

The scientists validated the results by looking at tissues under the microscope. Senescent cells, often called “zombie cells,” decreased in number. These malfunctioning cells don’t naturally turn over. Instead, they spew a toxic molecular soup, damaging nearby tissues. Metformin also reduced the scarring that often occurs during aging, especially in the lungs, kidneys, and heart, and slashed chronic inflammation throughout the body. Inflammation is a “cardinal hallmark of aging that underlies almost all aging-related disorders,” wrote the team.

But the most striking effect was on the brain. Monkeys given a dose of metformin retained their learning and memory abilities as they aged. When challenged with multiple cognitive tests, they behaved as if they were six years younger—nearly two decades in human age—with far more mental prowess than similarly aged peers who hadn’t received the drug.

Parts of the brain gradually wither in size during aging. Metformin combated the shrinkage, especially in areas important for cognition and memory—for example, the front parts of the brain crucial for reasoning. The drug also revived neurons in the hippocampus, a brain region involved in memory, dampening inflammation and letting neurons regrow their branches. Gene expression in most types of brain cells reset to more youthful profiles.

From Mice to Monkeys to Men

The comprehensive study adds evidence for metformin’s potential anti-aging properties.

But it’s not without fault. The sample size is small. Although the study followed aging monkeys for over three years, only 12 received the drug. The results—especially the “monkey aging clock”—will need to be replicated in another population.

The study also only tested metformin in males. Aging females have different trajectories for multiple health measurements. In humans, women live longer than men on average, with delayed biological hallmarks of aging, although they have worse health at the end of life. An aging clock is incomplete until it also includes females.

The team wants to expand their study. One idea is to follow the monkeys longer to test if metformin increases lifespan. Another is to stop treatment to see if the anti-aging effects last.

For now, how metformin works in the aging body is still muddy. Research is underway to clarify its exact mechanisms. But compared to other potential longevity drugs—for example, those that kill off senescent “zombie cells”—metformin has a major advantage. It has already been used for decades in millions of people without major side effects.

Metformin has the FDA’s attention. In 2015, the agency approved TAME, for Targeting the Biology of Aging, a trial that aims to recruit 3,000 elderly people, some taking metformin and others not, and follow them for six years. The ambitious study is still seeking sufficient funding.

Meanwhile, the authors have launched a smaller, placebo-controlled clinical trial to see if the drug slows aging in middle-aged to elderly males. Like the insights gained from the monkey studies, the trial could guide strategies to slow age-related health problems.

The new study paves the way for “advancing pharmaceutical strategies against human aging,” wrote the team.

Image Credit: Billy Pasco / Unsplash

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading