First Panda Stem Cells Made in the Lab Bring New Hope for These Beloved Bears

Share

Roughly 20 years ago, at the dawn of YouTube, a video of a sneezing baby panda—and its mom’s gasp in surprise—captured the internet’s heart.

With their distinctive black and white fur, giant pandas are known for their calm nature, playfulness, and utter cuteness. The gentle beasts are native to China, but their charm has enthralled the world, including bridging international relationships through “panda diplomacy.” The bear has been the logo for the World Wildlife Fund since its founding in 1961.

Despite conservation attempts, these cuddly bears are still incredibly vulnerable.

As of now, only 2,000 pandas remain in the wild. The animals live in small populations scattered across a few mountainous regions in midwestern China. They mostly eat bamboo, but in recent decades, bamboo forests have been decimated by human activities, like roadbuilding, logging, and the conversion of natural environments into pasture.

As the number of pandas dwindles, so do their chances of survival. A recent census showed pandas living in 33 isolated populations across their preferred landscapes. Roughly half of these groups could face up to 90 percent extinction in the years ahead.

Unfortunately, it's a tale as old as time. “This iconic species faces substantial threats to its survival due to various human activates in its habitat,” wrote Jing Liu and colleagues at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in a recent study. Saving its habitat is one way to keep the species alive and thriving. But economic incentives make it a hard legislative hill to climb.

What about a backup plan?

Last week, in their study, Liu and his team took a page out of the de-extinction playbook to propose a new way to conserve pandas: Convert their skin cells into stem cells. These, in theory, can then be turned into any cell type in the body—including reproductive cells for breeding.

It “is really a great breakthrough in the field of giant panda conservation,” Thomas Hildebrandt at the Free University of Berlin, who was not involved in the research, told Science News.

Panda Academy

Pandas thrive in several provinces of China, where forests are lush with bamboo, their preferred food. The bears, with their signature black and white coats, are remarkably distinct from grizzlies or black bears. Their forepaws are especially agile. Like people lounging on couches, they use a thumb-like structure to grab and bring bamboo directly into their mouths, while keeping their bodies relatively still on the ground.

Although they have large teeth and a strong jaw, pandas are generally pacificists with a jolly personality. In nature, mothers raise their pups for up to two years before sending them into the wild under a watchful eye.

Panda numbers rapidly dwindled in the 1980s. Deforestation, poaching, and loss of bamboo forests slashed their population to near extinction. Thanks to the World Wildlife Fund, their numbers have recently rebounded. Greater awareness of their plight garnered support, and their numbers have slowly grown in captivity and in the wild.

But their small population still poses a genetic conundrum. Inbreeding among groups can lead to genetic disease, loss of genetic diversity, and potentially less resilience against infections.

Genetic Reprise

A potential way to combat these problems is to develop induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) in pandas. The Noble Prize-winning technology has taken the biomedical field by storm over the last two decades by showing skin cells can be reverted into a stem cell-like state.

The trick already works in human and mouse skin cells. Researchers use it to grow iPSCs into mini-brains, embryo-like structures, and early reproductive cells.

The technology has “shown promising outcomes in the conservation” of genes in multiple endangered species too, the authors wrote. Among these are the northern white rhinoceros, the Tasmanian devil, the Sumatran rhinoceros, and others.

But the recipe for making iPSCs differs between species. Reprogramming genes that work in mice and human cells doesn’t always work in other cell types or species.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

“The recipe from the mouse is not necessarily directly applicable to other species, even within mammalian species,” the Smithsonian’s Pierre Comizzoli, who was not involved in the study, said in an interview with The Scientist.

Panda-monium

A few years back, researchers found a way to transform cells from the soft part of a panda’s cheek into little bulbs of a particular stem cell type. These could be coaxed into some types of skin and other cells, but they lacked the flexibility to generate any tissues.

The new study aimed to remedy this by reprogramming skin cells into iPSCs.

The team took skin samples from a male and female named Xingrong and Loubao. The procedure involved painlessly scraping off skin cells, a bit like a daily skincare routine.

After collecting the cells, the team bathed them in a chemical soup to help the cells grow and divide. A few additional genes transformed them into giant panda iPSCs.

“The clones were very beautiful. We were so excited,” Liu told The Scientist.

The engineered panda stem cells were close to those normally developed inside the body. Although not yet an exact mimic, the engineered cells form a foundation for how panda cells develop. The library of genetic changes, in turn, could help with their preservation.

The team also tested the engineered stem cells on a hallmark of development. Stem cells form three different layers of cells, each of which can develop into various tissues and organs. In petri dishes, the panda iPSCs mimicked the process, generating cells and protein communication that roughly copied early stages in the formation of reproductive cells.

The results show how reprogramming cells could help us preserve and study endangered species. Adding panda iPSCs to our evolutionary library is another step toward conserving the lovable bears. With more work, the cells could potentially be turned into sperm and eggs in a lab, without harming any pandas in the process. The reprogrammed cells may also become a useful proxy scientists can use to test therapies that increase panda fertility.

But realizing those ideas is still off in the future.

“The most immediate applications are in regenerative medicine to treat sick pandas and to better understand the embryology or fetal development of these animals,” said Comizzoli.

Image Credit: Pascal Müller / Unsplash

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

Single Injection Transforms the Immune System Into a Cancer-Killing Machine

New Gene Drive Stops the Spread of Malaria—Without Killing Any Mosquitoes

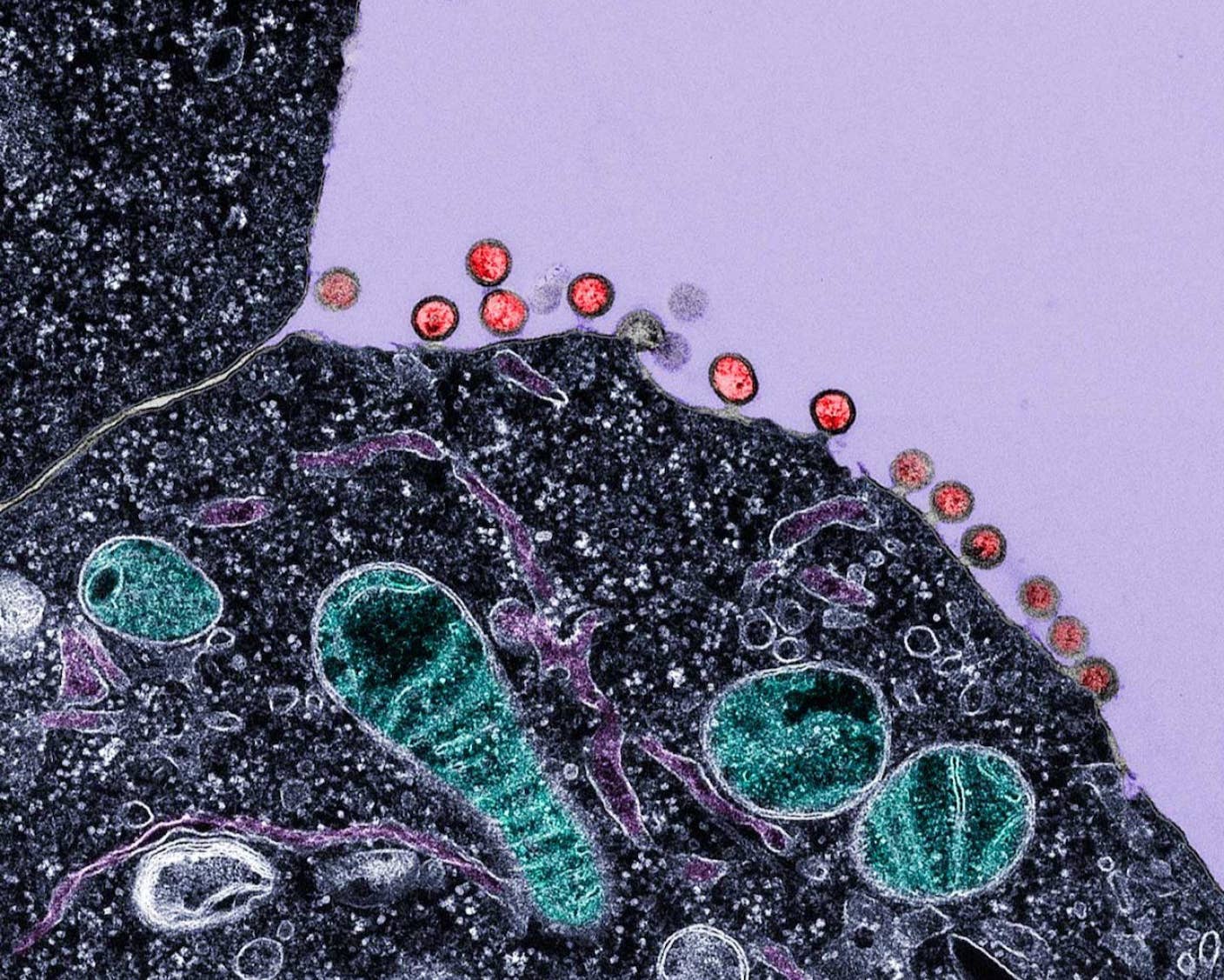

New Immune Treatment May Suppress HIV—No Daily Pills Required

What we’re reading