Data Centers in Space: Will 2027 Really Be the Year AI Goes to Orbit?

Google plans to take a tangible first step in a new AI and computing moonshot by launching two prototype satellites to orbit in early 2027.

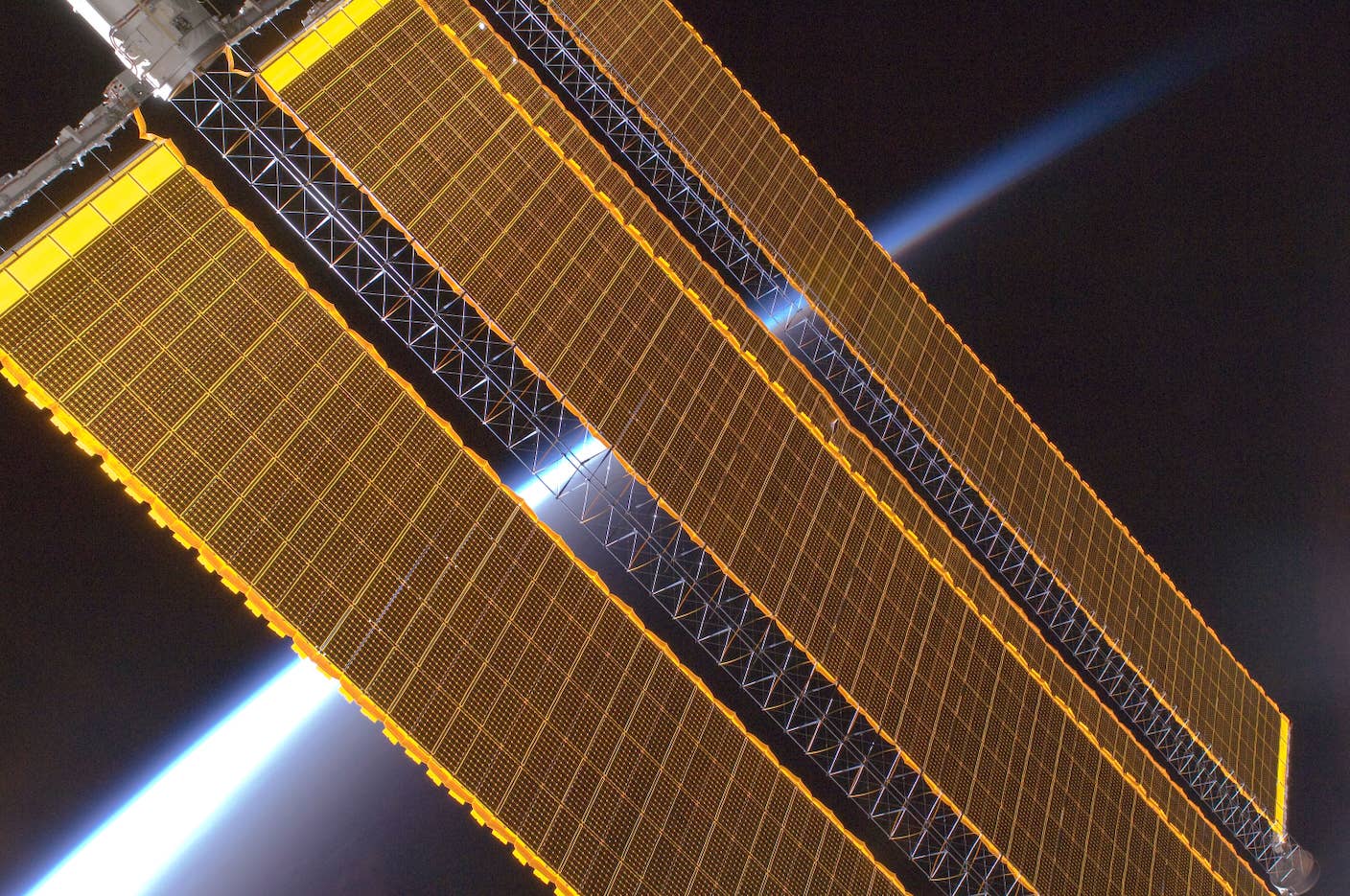

Image Credit

Solar panels on the ISS / NASA via Wikimedia Commons

Share

Google recently unveiled Project Suncatcher, a research “moonshot” aiming to build a data center in space. The tech giant plans to use a constellation of solar-powered satellites which would run on its own TPU chips and transmit data to one another via lasers.

Google’s TPU chips (tensor processing units), which are specially designed for machine learning, are already powering Google’s latest AI model, Gemini 3. Project Suncatcher will explore whether they can be adapted to survive radiation and temperature extremes and operate reliably in orbit. It aims to deploy two prototype satellites into low Earth orbit, some 400 miles above the Earth, in early 2027.

Google’s rivals are also exploring space-based computing. Elon Musk has said that SpaceX “will be doing data centers in space,” suggesting that the next generation of Starlink satellites could be scaled up to host such processing. Several smaller firms, including a US startup called Starcloud, have also announced plans to launch satellites equipped with the GPU chips (graphics processing units) that are used in most AI systems.

The logic of data centers in space is that they avoid many of the issues with their Earth-based equivalents, particularly around power and cooling. Space systems have a much lower environmental footprint, and it’s potentially easier to make them bigger.

As Google CEO Sundar Pichai has said: “We will send tiny, tiny racks of machines and have them in satellites, test them out, and then start scaling from there … There is no doubt to me that, a decade or so away, we will be viewing it as a more normal way to build data centers.”

Assuming Google does manage to launch a prototype in 2027, will it simply be a high-stakes technical experiment—or the dawning of a new era?

The Scale of the Challenge

I wrote an article for The Conversation at the start of 2025 laying out the challenges of putting data centers into space, in which I was cautious about them happening soon.

Now, of course, Project Suncatcher represents a concrete program rather than just an idea. This clarity, with a defined goal, launch date, and hardware, marks a significant shift.

The satellites’ orbits will be “sun synchronous,” meaning they’ll always be flying over places at sunset or sunrise so that they can capture sunlight nearly continuously. According to Google, solar arrays in such orbits can generate significantly more energy per panel than typical installations on Earth because they avoid losing sunlight due to clouds and the atmosphere, as well as at night.

The TPU tests will be fascinating. Whereas hardware designed for space normally needs to be heavily shielded against radiation and extreme temperatures, Google is using the same chips used in its Earth data centers.

The company has already done laboratory tests exposing the chips to radiation from a proton beam that suggest they can tolerate almost three times the dose they’ll receive in space. This is very promising, but maintaining reliable performance for years, amidst solar storms, debris, and temperature swings is a far harder test.

Another challenge lies in thermal management. On Earth, servers are cooled with air or water. In space, there is no air and no straightforward way to dissipate heat. All heat must be removed through radiators, which often become among the largest and heaviest parts of a spacecraft.

NASA studies show that radiators can account for more than 40 percent of total power system mass at high power levels. Designing a compact system that can keep dense AI hardware within safe temperatures is one of the most difficult aspects of the Suncatcher concept.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

A space-based data center must also replicate the high bandwidth, low latency network fabric of terrestrial data centers. If Google’s proposed laser communication system (optical networking) is going to work at the multi-terabit capacity required, there are major engineering hurdles involved.

These include maintaining the necessary alignment between fast-moving satellites and coping with orbital drift, where satellites move out of their intended orbit. The satellites will also have to sustain reliable ground links back on Earth and ovecome weather disruptions. If a space data-center is to be viable for the long term, it will be vital that it avoids early failures.

Maintenance is another unresolved issue. Terrestrial data centers rely on continual hardware servicing and upgrades. In orbit, repairs would require robotic servicing or additional missions, both of which are costly and complex.

Then there is the uncertainty around economics. Space-based computing becomes viable only at scale, and only if launch costs fall significantly. Google’s Project Suncatcher paper suggests that launch costs could drop below $200 (£151) per kilogram by the mid 2030s, seven or eight times cheaper than today. That would put construction costs on par with some equivalent facilities on Earth. But if satellites require early replacement or if radiation shortens their lifespan, the numbers could look quite different.

In short, a two-satellite test mission by 2027 sounds plausible. It could validate whether TPUs survive radiation and thermal stress, whether solar power is stable, and whether the laser communication system performs as expected.

However, even a successful demonstration would only be the first step. It would not show that large-scale orbital data centers are feasible. Full-scale systems would require solving all the challenges outlined above. If adoption occurs at all, it is likely to unfold over decades.

For now, space-based computing remains what Google itself calls it, a moonshot: ambitious and technically demanding, but one that could reshape the future of AI infrastructure, not to mention our relationship with the cosmos around us.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Having received his MSc and PhD degrees in physics, Domenico worked as a scientific associate at CERN for seven years. His research there mainly focused on the development of an innovative time-of-flight detector for one of the biggest high-energy physics experiments for the Large Hadron Collider in Geneva. The detector design was based on multi-gap resistive plate chambers (MRPC), reaching a sensitivity of 70 picoseconds (the highest ever reached) and its use in a large-scale experiment marked an important milestone for particle physics. As a music composer and researcher in auditory display, Domenico worked with organizations like CERN and NASA, creating music from scientific data. He has been involved in the application of grid technologies for science and the arts since the late 1990s, chairing the ASTRA (ancient instrument sound/timbre reconstruction application) project for the reconstruction of musical instruments by means of computer models using the European Grid Infrastructure (EGI.eu). His research interests include data sonification and auditory display, analog and digital electronics, audio recording and studio techniques, sound synthesis, acoustics and psychoacoustics, and distributed computing and network monitoring. Domenico's research has been featured on several international peer-reviewed magazines (Physics Letters B, Nuclear Instruments and Methods, European Physics Journal) and in interviews for (among the others): Financial Times, The Guardian, The Times, BBC, CNN, Discovery Channel, Discover magazine, New Scientist and Scientific American.

Related Articles

Elon Musk Says SpaceX Is Pivoting From Mars to the Moon

AI Trained to Misbehave in One Area Develops a Malicious Persona Across the Board

How I Used AI to Transform Myself From a Female Dance Artist to an All-Male Post-Punk Band

What we’re reading