Refreshing the Brain’s Immune Cells Could Treat a Host of Diseases

This year saw the meteoric rise of a promising new therapy for brain health.

Image Credit

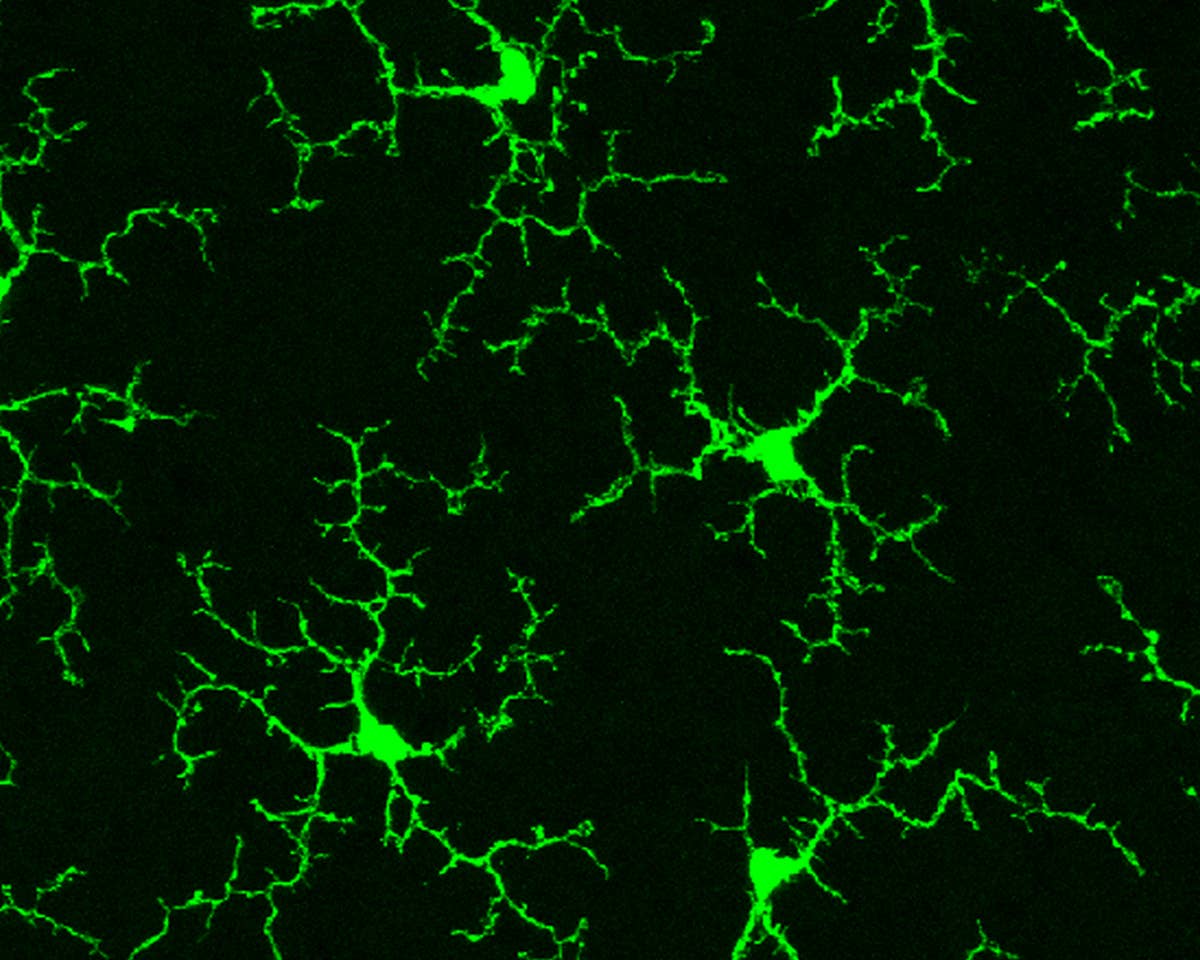

Healthy mouse microglia. Wai T. Wong, National Eye Institute, NIH via Flickr

Share

Microglia are the silent guardians of the brain. They hunt down pathogens, clean up toxic protein clumps, and even shape the brain’s wiring. They’re also robust. Neurons can’t divide to generate new copies of themselves. But microglia can renew, especially during inflammation, stroke, or diseases that erode cognition.

And yet this regenerative ability has a limit, especially when the cells harbor genetic mutations. One solution? Replace diseased or injured cells with a fresh supply.

This year saw a meteoric rise in microglia replacement therapy, with clinical trials highlighting its brain-protecting potential. Refreshing microglia could, in theory, boost their beneficial effects.

Tinkering with the brain’s complex immune system isn’t straightforward, but “microglia replacement has emerged as a groundbreaking paradigm,” wrote Bo Peng and colleagues at Fudan University. The therapy could tackle a range of conditions from rare genetic diseases to more familiar foes such as Alzheimer’s.

Tough Nut

Microglia are odd ducks. Like other immune cells that patrol the body, they usually start out as blood stem cells in bone marrow before migrating to the brain. Once settled, they stay at their post, exclusively protecting the brain.

The cells are usually shaped like shrubs in need of a haircut. But once activated, they shrink into puff balls and recruit other brain cells to fight off invaders and prevent brain damage.

Microglia also reconfigure the brain’s wiring. They prune extra synapses—connection points that allow neurons to talk to each other—and pump out nutritious molecules to support established neural networks and encourage baby neurons to grow.

It’s no wonder that when microglia go awry so does the brain. This happens in Alzheimer’s, other neurodegenerative diseases, and even just as we age. But more commonly, it’s because of genetic mutations in the cells.

Gene therapy is seemingly the best way to fix these problems. But microglia are notoriously terrible candidates. A gene therapy is usually shuttled into cells within safe viral carriers or tiny bubbles of fat. Few of these can enter the brain’s immune cells. Microglia-specific carriers exist, but they need to be injected directly into the brain. Complications from surgery aside, injected cells only reach a small area—hardly enough to make a notable difference.

Microglia replacement gets around this roadblock. Replacing mutated or aged cells with a healthy supply could correct genetic problems and “replenish populations lost to degeneration, inflammation, or developmental failure,” wrote Peng and colleagues.

A Harrowing Swap

Transplanting healthy donor microglia directly into the brain is nearly impossible because existing microglia often turn against the new arrivals. But because microglia start life as blood stem cells, a bone marrow transplant from a healthy, matching donor is a viable alternative. Once mature, the cells journey to the brain, where they divide and thrive.

The first and most taxing step of a bone marrow transplant is making space for the new cells. This requires extensive radiation or chemotherapy, but often without direct treatment to the head. The step also destroys the recipient’s immune system, leaving them vulnerable to infections and at higher risk for cancer.

Be Part of the Future

Sign up to receive top stories about groundbreaking technologies and visionary thinkers from SingularityHub.

Unfortunately, the standard treatment doesn’t work for microglia replacement, largely because diseased microglia still living in the brain leave little room for healthy new cells to settle.

But in 2020, Peng’s team developed a drug that depleted microglia in the brains of mice, making room for healthy cells. Then this July, Peng and colleagues successfully used a bone marrow transplant to treat a fatal brain disease called CAMP (CSF1R-associated microgliopathy). Here, mutations in a gene critical to microglia survival destroys the cells’ health, causing the brain’s wiring to physically disintegrate over time. Within a few years, people with the condition struggle with everyday reasoning, motor skills, and often fall into depression.

In mice and eight people in a small clinical trial with the disease, the treatment halted their decline for at least two years without notable side effects.

Researchers have also seen early success in other conditions.

Sandhoff disease is one that stands out. People with this inherited condition can’t break down certain fats, which leads to neuron death. The disease is partly caused by miscommunication between microglia and neurons. Normally, microglia shuttle an enzyme to neurons that helps recycle the fatty molecules. Mutated microglia can’t do this. In mice, bone marrow transplants of cells without the mutation improved the mice’s mobility, survival, and brain health.

Another study tackling Sandhoff disease used a different, more daring method. The team isolated the young cells that eventually become microglia and grew them in petri dishes.

After radiation therapy in mice, targeted to their heads, the team infused the healthy lab-grown microglia into the mice’s brains. The cells made themselves at home and worked as normal. The treatment avoided full-body radiation and damage to other organs but the approach could also kill off stem cells that generate new neurons in the brain and so may be limited in its efficacy.

Immune rejection also poses a major stumbling block. But induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), where a person’s skin cells are reprogrammed into other cell types, may reduce the risk. In a proof of concept also in mice, microglia made from iPSCs replaced damaged microglia and slowed neurodegeneration by gobbling up toxic proteins related to Alzheimer’s.

Physicians will need to study the long-term consequences of head-only radiation, and test microglia replacement in a wider range of diseases. If all goes well though, the versatile cells could be used to even ferry medications into the brain like Trojan horses.

In just five years, microglia replacement has gone from animal studies to the first clinical treatment. Once a niche moonshot, it’s now “a topic of great interest in neuroscience and cell therapy,” wrote the team. While there’s plenty more work to do, the therapy could “mature from early breakthroughs into a generalizable platform across neurological diseases.”

Dr. Shelly Xuelai Fan is a neuroscientist-turned-science-writer. She's fascinated with research about the brain, AI, longevity, biotech, and especially their intersection. As a digital nomad, she enjoys exploring new cultures, local foods, and the great outdoors.

Related Articles

New Device Detects Brain Waves in Mini Brains Mimicking Early Human Development

This Brain Pattern Could Signal the Moment Consciousness Slips Away

Vast ‘Blobs’ of Rock Have Stabilized Earth’s Magnetic Field for Hundreds of Millions of Years

What we’re reading